Craig Austin discusses the Glam era of music and culture in Britain during the 1970s through the lens of the most popular music stars and Welsh professional wrestler Adrian Street.

For the thousands of Saturday night city-centre boozehounds presently tearing up the perversely-branded retrospective theme bars of the nation, the 1970s must seem like a peculiarly bygone golden age where cheery glitter-strewn postmen went about their business in towering platform boots, and the factory floor’s most frequent industrial injury must surely have been the random trapping of a perfectly coiffured white man’s afro in a printing press or a machine tool. The reality of course, could not have been more diametrically opposed.

The 1970s was a decade of almost perpetual mayhem – an epoch of economic cataclysm, relentless terrorist activity, outrageous state-endorsed discrimination, and the recurrent threat of random and brutal street violence. Throw in a shadowy backdrop of terrifying Cold War menace and it would be hard to dispute the bleakly austere summary of Francis Wheen in his exemplary and entertaining encapsulation of the decade, Strange Days Indeed: The Golden Age of Paranoia: ‘Slice the 70s where you will, the flavour is unmistakable – a pungent mélange of apocalyptic dread and conspiratorial fever.’ Moreover, when the terminally doomed alien visionary Ziggy Stardust sang apocalyptically about us only having ‘five years left to cry in’ there were many who overlooked its overtones of pop art and science fiction and sincerely believed that to be our immovable destiny.

In the midst of such turmoil, almost certainly because of it – and most perversely of all, at a time when the likes of Bowie, Eno, and Roxy Music were looking so resolutely to the future – the UK and the USA seemingly conspired, via the prevailing medium of pop culture, to hark back to their own theoretical ‘golden age’ of rose-tinted societal safety; the circle-skirted, velvet-trimmed conventionality of the 1950s. A singly bizarre phenomenon that eventually spawned, in the US, the retro-themed boy-meets-girl Hollywood cash-cow of Grease, and, in the UK, the entirely unexpected revival of the drape-coated Teddy Boy; a recycled, self-loathing ‘youth’ culture predominantly populated by angry middle-aged men with thinning quiffs and sharpened blades.

Conversely, and no doubt to the teds’ seething chagrin, it was Marc Bolan and David Bowie – two fastidiously tailored suburban mods of the 1960s, no less – in whom the nation’s pop fans ultimately invested their obsessive faith and devotion. As the unmistakable and unapologetically effeminate figureheads of a multi-layered and multifaceted scene that encompassed the assorted contributions of art school visionaries, avant-garde designers and shameless cultural opportunists – one that swiftly adopted the conveniently catch-all moniker of Glam – they planted an aspirational seed of ambition within an audience that would later bear abundant fruit in the flourishing of the British ‘new pop’ phenomenon that would take the world by storm a decade or so after the event.

Though subsequently demeaned as both Thatcherite and self-regarding in its open embrace of la dolce vita, the ‘riches’ lusted after by the ‘Blitz kid’ generation of Spandau and Duran were ultimately no different to those pursued by their template-setting Glam precursors and the first generation of what would become known as punk; a repudiation by working class men and women of the rigid and joyless framework of humble toil and know-your-place deference that society had sought to set out before them, a rejection of the petty morals and failed ideals of their parents’ generation via a unique form of personal and aesthetic renaissance.

It’s often said that periods of social and economic turmoil are the ideal inspirational breeding ground for the creation of trailblazing, and occasionally revolutionary, art and in Glam – a proto-punk for those who despised the notion of anything as conventionally gauche as a manifesto – the prevailing bleak economic circumstances of the early 1970s inspired a relative few to kick over the social and cultural statues of their starch-shirted forefathers and to seek to rebuild the nation for the many, in their own deliciously provocative image. A Cavalier-led assault upon a still decidedly Roundhead society by the preening peacock sons and daughters of a generation still collectively entrenched in the lethargic mindset of Upstairs Downstairs and World War II.

‘Wake up you sleepy head / Put on some clothes, shake up your bed’, a pre-Ziggy Bowie had intoned during the opening bars of ‘Oh, You Pretty Things’, a rallying call to arms to those seemingly intent – almost literally – on ‘driving your Mamas and Papas insane’. In doing so, they generated some of the most exciting pop culture that this country has ever witnessed, provided a fitting backdrop to an increasingly politicised campaign for sexual liberation and transformed themselves into obsessively flamboyant works of high-street art; an inspirationally indefinable philosophy that paradoxically inspired some of the greatest musicians, designers and film-makers of the era. A groundbreaking and pioneering means of presenting oneself to the world not lost upon a resolutely determined coal miner’s son from Brynmawr, South Wales…

Much like mod, and the imminent punk movement that was in so many ways inspired by it, Glam was always more than just a visual style, defining an attitude and a state of mind as much as it did a haircut or a record sleeve. Latterly, and erroneously, dismissed as both novelty and nonsense, it brought about an almost revolutionary appreciation of self-identity and a sense of escapist emancipation among its wide-eyed devotees that bulldozed a way through the once seemingly impregnable barricades of class and gender. In doing so, it crafted an alternative projection of masculinity that set the template for so many of our future stars and which blew away decades and centuries of received wisdom about gender identity and the rules of attraction.

Tate Liverpool’s current and remarkable exhibition, ‘Glam! The Performance of Style’, seeks to encapsulate the almost limitless breadth of the movement’s cultural impact, going far beyond the realms of pop music to encompass photography, film, literature and design. Knowingly split between the British phenomena of Bolan, Bowie, Biba and Oz and a more fractured, yet equally essential U.S. scene that orbited around Warhol, Lou Reed and The New York Dolls, ‘Glam!’ seeks to present the period as an unapologetically jarring schism that saw off any remaining vestiges of the ailing 1960s and as one which set the cultural tone for the rest of the 1970s and much of the 1980s; one that doesn’t shy away from the fact that, in Britain at least, much of the scene was indeed made up of the archetypically opportunistic ‘hod-carriers in mascara’ of contemporary legend.

As content as Ian Hunter’s Mott the Hoople were to kiss the painted hand that fed them – it took a Bowie-penned song, the immense ‘All The Young Dudes’, to give them their first proper hit – it didn’t stop Hunter bemoaning a seismic change in fashion that was frequently felt to enforce vagaries of unwanted ‘poovery’ upon the less stylistically inclined.

‘Glam!’s eclectic collection of period ephemera; the Antony Price clothing, the pulsating Roxy music soundtrack, the soft porn and fetish fashion, is perfectly complemented by the much less glamorous, but equally valid, representation of ‘fandom’ and the often solitary experience of the aspirational bedroom dreamers who alleviated their otherwise dreary existences via the glittering alternative ideal for living offered up by the likes of Ferry, Bolan, Bowie et al.

American photographer Nancy Hellebrand’s unembellished and acutely intimate black and white images of teenage Glam devotees captured in their own homes presents the stark contrast between the drab bedsits of her subjects and the manifest escapism represented by the glamorous posters pinned to their walls; the crippling recession of the early 1970s jostling for space with what was, in essence, the decadent cabaret culture of 1930s Berlin.

As a ‘crash course for the ravers’ it’s a lovingly assembled triumph and, though its deserved plaudits are likely to be suffocated by the overarching shadow currently being cast by Bowie’s ‘best-selling show’ at the V&A, it succeeds in touching the more unconventional and unashamedly outré elements of a scene eternally rooted in the obscure and provocative. For many visitors, however, it won’t be the celluloid 50s/sci-fi leer of Bryan Ferry or the aggressively sexual imagery of Allen Jones’ ‘Table’ and ‘Chair’ that forms their abiding memory of ‘Glam!’ Not when a startling juxtaposed monochrome image of clashing generational cultures screams out at them from the headframe of a South Wales mineshaft.

‘Adrian was one of those misfits that was always involved with the intrigues of life,’ recalls wrestling promoter Max Crabtree, in conversation with Simon Garfield, author of the exemplary The Wrestling:

‘He never had the great success of a (Mick) McManus, but he did register. But the promoters didn’t particularly like what he did. He was a complex man. He liked to portray the role of a poof but, behind that façade, if one of the customers said to him, “Get out of it you bloody poof, Street!” he’d be at them. And you had to watch him, because Adrian would do anything for attention. He would have shown his private parts on television if he thought it would have done him some good.’

Professional wrestler ‘Exotic’ Adrian Street remains a cruelly overlooked footnote in Welsh sporting/showbiz history (delete as appropriate). Though long-since relocated to Northern Florida, this iconic image of a preening Street, in flamboyantly full flowing Glam regalia, and his father, a weathered coal miner of fifty-one years and a former Japanese POW, remains the picture-perfect encapsulation of the generational and social conflict that was writ large through much of the 1970s; the confusion, the bafflement and the fear.

Born in the Welsh mining town of Brynmawr in 1940, Adrian Street left school at the age of fourteen and fell for the allure of the wrestling ring upon seeing his first live bout in Newport. In conversation with Garfield, he recalled, ‘I thought the wrestling was great, but the characters were so dull. Everyone wore the same. Big woolly black trunks and little black or brown boots, but I was used to seeing all the characters from America.’ Having moved, alone, to London at the tender age of sixteen – much like moving to Mars for a South Wales valley boy in the mid-1950s – he ‘slogged around for a long while’ before creating an image for himself more resonant of Bolan than Big Daddy; an outrageous collision of make-up and glitter, the wrestler’s long shaggy hair dyed platinum blond and teased into cutesy schoolgirl pigtails:

‘I got my image and things began to take off for me as soon as I had that established. To begin with the promoters said, “Oh, you don’t want to carry on like a queer” but in time they realized what a draw I was for them.’

Though unapologetically heterosexual, Adrian Street openly embraced the fast-shifting patterns of social behaviour and used them to his personal and professional advantage. Whilst it would be convenient to label him a cultural opportunist, (particularly in terms of the public perception of his then ambiguous sexuality), it is hard to grasp quite what a precarious and confrontational image he ultimately chose to adopt, not least for a working class Welsh male from an almost aggressively heterosexual community:

‘Back in the dressing room the other wrestlers were a bit confused by it and thought maybe it was for real. And I used to mince and turn it back on them. I would wait until everyone else was in the shower and the glide in with the towel under my arms and go, “Mmmm, a smorgasbord!” The place would empty.’

Whilst the seeds of what was then know as ‘gay liberation’, an increasingly political and militant movement, were slowly being sown, the prevailing image of gay men on primetime TV remained either purposefully asexual or anaemically unthreatening. Adrian Street, despite his own sexuality, represented the antithesis of this and in doing so must surely have initially elicited, in some quarters, a reaction on a par with that of Bill Grundy’s notorious Sex Pistols inquisition. For such a doggedly independent and wholly unique man it’s not even entirely clear as to what degree – if at all – Street attributed his own image to the similarly perfumed music scene that flourished in parallel with his own.

What is evident, however, is that devoid of either guitar or microphone, ‘Exotic’ Adrian Street was a pop star in the truest sense of the term and one who remains a groundbreaking and influential icon to this day. Though wholly aware of the significance of his place within the artistic scheme of things – ‘The fans hated it, but you could tell they were intrigued and I think the women were maybe a bit turned on. Nobody was doing that before me. Boy George wasn’t even born when I started’ – he remains one of his nation’s most criminally overlooked cultural icons and, crucially, in his own words, ‘a fucking good wrestler’.

On March 13th, just 10 days before the official opening of the V&A’s David Bowie Is… Adrian Street fought the final bout of his career in Alabama. Street estimates that during his career he has wrestled between 13,000 and 16,000 matches. He is seventy-three.

The very fact that an exhibition, in one of the nation’s most revered museums, in honour of a sixty-six year-old man, forms the cultural and stylistic highpoint of the UK’s contemporary music scene, says much about a barren pop culture in which – to appropriate a fine 1970s theme tune – ‘the only thing to look forward to is the past’. David Bowie is… has become such a resoundingly essential phenomenon – the V&A’s most successful event since it chose to honour the legacy of another of the nation’s Dames, one Vivienne Westwood – that not to have an opinion on either it, or its recently revitalised subject matter, renders you almost socially inconsequential. And with good reason.

As Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp (an early devotee and an exhibition talking head) remarks, ‘Bowie was nothing less than a form of subversive conceptual art delivered through the medium of popular culture.’ Given the astonishing amount of hype that has accompanied the lead-up to the exhibition’s launch it would be slightly unusual if visitors were not in some small way underwhelmed by the fact that it’s, well, just an exhibition. An exhibition devoted to arguably the nation’s greatest ever pop star, but a showcase of things nonetheless. And David Bowie has always been more than just about ‘things’.

The outfits that looked so futuristic and glamorous on a 1970s TV screen – though innovative and trailblazing in their conception – look fragile, disposable and inexpensive within this context and without the avant-garde stagecraft that truly brought them to life; an appositional compromise of intent and resource that typifies the early 1970s and the ‘make do and mend’ reality of a society that to all intents still remained in hock to the financial liabilities of World War II and whose grandchildren still played amongst its bombsites. When the Spiders from Mars brought their traveling Technicolor carnival to the forgotten northern industrial towns of Preston and Doncaster – a string of dates often overlooked by the historical records in favour of the legendary Hammersmith gigs that closed the book on both the tour and The Spiders themselves – they played those shows in a series of relatively tiny music halls that looked almost exactly the same as they had prior to war breaking out in 1939. This was Glam done in the only way that Britain knew how to operate at the time: on the cheap.

For many, including those who paraded the trappings of this brave new world on Top of the Pops, the slick veneer of glamorous escapism hid a multitude of sins rooted firmly in the economic malaise of the period; a pessimistic sense of interminable despair and the ominous threat of totalitarian government reflected in the Clockwork Orange-aping stage sets and outfits of the ‘Ziggy’ period. It’s a mind-set that Bowie publicly obsessed over for a period of years, one that the V&A seeks to represent in its artistic context and which, fueled by the ready availability of the purest cocaine on the market, began to manifest itself in ways that started to alienate the artist from many of his early devotees.

Any reference to the notorious Victoria station ‘salute’, a stubborn stain upon the sartorial elegance of the Thin White Duke, is a wholly predictable omission from an event focused purely on the celebration of the artist’s legacy and cultural impact. It is this period, the Berlin-based ‘black and white years’, that forms the most fascinating element of the exhibition. Whether it be a letter on headed Hansa Studios notepaper addressed to ‘Herr Tony Visconti’ or the mere notion of a body of work primarily recorded whilst looking directly onto the watchtowers and machine gun turrets of the Berlin Wall (or the ‘Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart’ depending on your 70s geo-political worldview), this representation of a peerless trilogy of albums that Bowie himself described as being his ‘DNA’ is both darkly evocative and appropriately self-contained.

Then suddenly we find ourselves back in Queen Caroline Street, a towering floor-to-ceiling canvas upon which are projected the most iconic moments of the final ‘Ziggy’ shows at Hammersmith Odeon. When Bowie famously spoke about how he couldn’t ‘stand the premise of going on (stage) in jeans and being real’, a statement he qualified by the hilarious adjunct ‘it’s not normal’, he was sat in the dressing rooms of the same venue, his face a picture of studied artistic otherness.

Four decades after the event, and having viewed the exact same footage on dozens of previous occasions, the sweepingly magnificent intensity of this experience is still an indisputable ‘hairs on the back of your neck’ moment, an emotion felt most acutely during the final act of ‘Rock’n’Roll Suicide’ as it builds towards its grandiose denouement. It remains the template for those who went on to remodel their image from the remnants of Bowie’s own, and for anyone who has ever been dragged from the wreckage by the thrillingly restorative healing power of rock’n’roll. To know what it is to be, or to have been, a fan. A magnetically irresistible stranger – be it Morrissey, Manson or Gaga – reaching out to take your hand and speaking the only words that can take the pain away:

‘You’re not alone’.

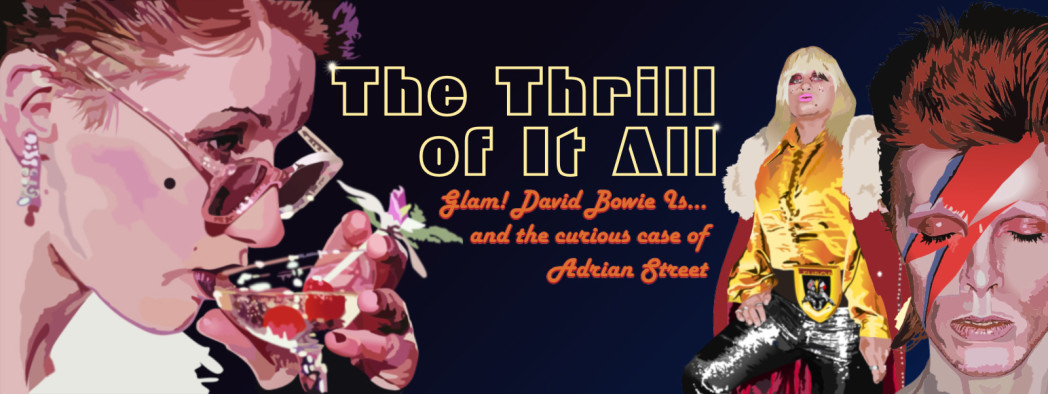

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis