Gary Raymond attended Richard III Redux, Sara Beer’s one woman show, and found that while it raised valuable questions in the portrayal of disability, it has perhaps not arrived at a solution to the issue.

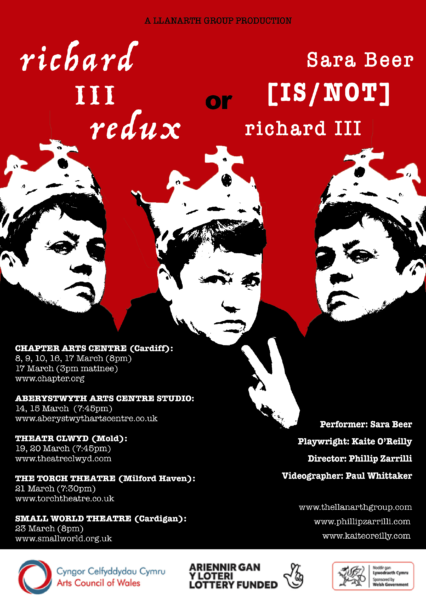

If you’re going to pose questions in a public sphere, one safety tip might be to know in advance what you’d like the answers to be. Few artists achieve greatness through naiveté, and fewer still offer provocation with no idea what will come back at them. For the Llanarth Group, in fairness, it seems this possible mistake might be the result of modesty – itself a rare commodity in any type of theatre – but when deconstructing Shakespeare it seems almost risky. Sara Beer’s one woman show, Richard III Redux [or] Sara Beer is/not Richard III, pushes and pushes and pushes, asks us to re-evaluate one of the Bard’s most iconic creations, asks us to shuffle in our seats at the very idea that Shakespeare’s Richard was ever acceptable, and yet doubts remain that by the end it has the courage of its convictions.

But solid convictions they are. Beer’s monologue winds through a history of acting theory, quaint (and often very moving) autobiography, and this central thread, the meat of it all – the life of a physically “abnormal” actor trying to make a way through a business obsessed with narrow ideas of aesthetic value. The failure of the system Beer and actors like her have been continually rejected from is on stage here for all to see. Beer is a captivating figure on stage, charming and erudite, extremely good company. This performance alone is a damning indictment of an industry that actively discourages disabled actors from entering, for it is the industry that has been missing out.

Beer is also very frank, which is something theatre like this always needs. She was born with the same condition as the historical King Richard, a hero and revered warrior, made villain by the needs of Shakespeare’s tragedy (both artistically and politically). Beer tells of how her place in the social hierarchy of the school she grew up in in west Wales changed forever when the film version of Olivier’s Richard III came to town. Suddenly her hunchback, for the first time, was connected to wickedness in the eyes of her peers. And not just wickedness, but a particular type of scheming untrustworthiness.

And this is where the first problem for Shakespeare comes up, but it is also a problem for Redux. There is no separating Shakespeare’s Richard from his villainy, and his villainy is absolutely intertwined with his deformity – it is enmeshed in the poetry of his evil state. Redux’s challenge, then, is to come to terms with that, and it never really does.

On a theatrical level, Redux is a strong piece of work. Conceptually it does well to make the multimedia aspect feel natural and important, rather than gimmicky. Director Phillip Zarrilli likes his visual jokes – two big screens that form the backdrop, for instance, are mounted on white sheets that trail off into half-visible bloodstains, reminding us where all tragedies must end up with a wink. Writer Kaite O’Reilly delivers something much simpler than her most exciting work, but she has sacrificed some artfulness in her writing to the play’s need for directness, which is no small achievement for any writer.

But afterwards there is an overwhelming feeling that somewhere theorising won over where some anger would have served better. Redux is ponderous; not a damning criticism on its own, but it introduces issues that are vital and relevant, and are screaming for swords to be drawn, but all we get is a kind of affable disgust with the status quo.

A sequence of stills from famous stage productions of Richard III are shown on the screen backdrop at one point, displaying the monstrosities of actors’ creative splurges on the king’s deformity. In this light, the entire creative process behind award-winning productions is extremely discomforting to comprehend. O’Reilly by this point has already joked about Diderot’s theory of paradox, and we have seen Beer deliver anecdotes from a wing-backed chair rather like Peter Sellers in his Beatles pastiche, but here we are into the serious stuff of now. Anthony Sher’s arachnoid Richard is horror-movie stuff, and Lars Eidinger’s kinky corset is also more Maitresse than Machiavelli, but in there is also Kevin Spacey’s braced leg from the hammy Old Vic production of 2011, and we realise where everything intersects. The corrupting dominance of men does not just lie in their privilege and whiteness – it also is entangled in their physical ableness. The further you look, the further to the horizon stretches the most important issues of time, issues of diversity. In Sher’s book, The Year of the King, about the process of creating the role for the RSC in 1985, he writes about visiting “spastic” hangouts on research trips. The levels of grotesque insensitivity to the facts of the physical demands of the role is staggering. Redux is full of grenades like this one, dropped with disarming gentility by Beer.

The question that Redux is perhaps not prepared for, then, is whether Shakespeare’s play should be performed at all in its traditional format in this time of activistic reappraisals? Or rather, what do we think of a producer or director or actor who sees it as appropriate to put on a play where the main character’s villainy is intrinsically linked to his physical disability? Have the three creative forces behind this deconstruction – O’Reilly, Zarrilli, and Beer – really considered this? The timidity of the ending suggests not. Redux quietly and charismatically introduces the idea of change, but has little to offer in terms of what a revolution might look like. It seems an important conversation must be had as to whether a “traditional” production of Richard III has a place on the modern stage at all. Arguments over anti-Semitism in The Merchant of Venice have it seems been dismissed as academic long ago. The guardians of our stages seem to want to have their cake and eat it, to simultaneously have pride in Shakespeare and his unfathomable global influence, and to deny his cultural influence at all. The truth is Shakespeare always comes first, and damn all else.

But there is nothing wrong with looking at great art and saying it is outmoded if is a demonstrably cruel and ugly influence. This is not censorship, this is expecting the creators of our theatre to ask themselves why they are approaching a certain text in the first place. It is asking our critics to throw out the rulebook, and to judge everything on its moral value in terms of representation, inclusivity, and diversity. Shakespeare’s Richard III has taught the world – every corner Shakespeare has reached – that to be physically defomred is to be untrustworthy, is to be wicked. That cruelty bleeds deep into the very fabric of the First Folio. So for what reason, other than conceit, would we continue to perform it? Richard III Redux may not be prepared to wrestle with these questions, but I’m afraid it’s the ones it has asked.

Richard III Redux [or] Sara Beer is/not Richard III is currently on tour around Wales. More details can be found here.

Gary Raymond is an editor and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

You might also like…

Given the muted 25th anniversary of the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, playwright Greg Glover takes a journey through personal acceptance, institutional ignorance and the changing nature of inclusivity in the theatre industry.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.