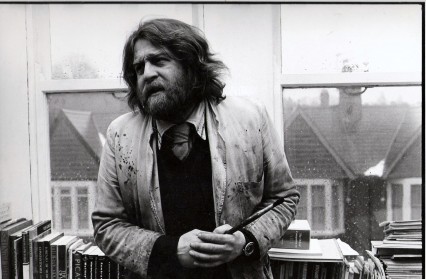

In this first part of a humourous and warm tribute to his friend, Martin Hamer recollects his teenage years with artist Tony Goble, a story of hitchhiking, poetry and dosshouses in 1960s Wales and England. In further instalments, Martin retells as he watched Tony develop into the renowned and much-loved artist, and he reflects on the critical reception of his work.

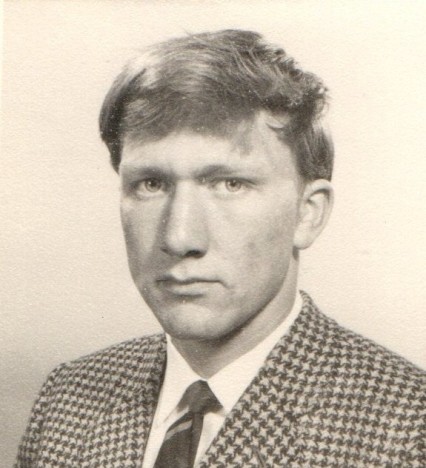

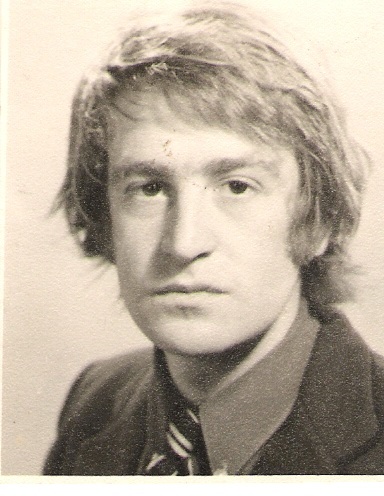

I had heard of him but I didn’t come across Tony Goble in person until 1959 when I was fourteen and he was a year and a few months older. We were playing football on the green opposite the open air swimming pool in Rhos-on-Sea near the old marionette theatre. He was on the opposing side and I was in goal. He was a beautiful young man with his long blonde hair and slightly balletic way of navigating the pitch.

A lad stood behind me on the goal line and, clearly in awe of Tony, gave me a synopsis of his recent history. He was in the Merchant Navy and had saved the lives of all souls when as the only sober man on board he had steered his shipmates through the dangers of The Solent. This was manna to a boy like me still faced with ‘O’ Levels at Colwyn Bay Grammar School with little immediate chance of being one of those in peril on the sea.

Tony and I were drawn to each other in this small community by politics and poetry. I was a badge-wearing member of CND. Tony joined The Committee of 100, a rather more radical organisation which boasted Bertrand Russell as its most controversial celebrity.

Otherwise we inhabited different worlds. I was at The Grammar School whereas Tony seemed to pick randomly at educational opportunities. He was not sporting and I was. My life pretty much revolved around rugby, cricket and the Debating Society. With my debating experience and still only 15, I was elected Chairman of Colwyn Bay and Llandudno CND and this was when I came into contact with Tony again. Anything radical going on and he would be there.

There was a group of us who met in the house of car salesman Keith in Penrhyn Bay. Sometimes someone would upset Keith as I once did by suggesting Harold Wilson was not a crusading socialist. He was a Well if you believe that you can fuck off. I’m going to read The Guardian in the lavatory sort of a guy; an abrasive soul. His wife studied to be a social worker and ran off with her first case. This betrayal became his sole subject of conversation and Tony and I began avoiding him in pubs.

Keith was something of a literary pioneer and had been to see Waiting for Godot in Liverpool. He declared he hadn’t got a clue what it was about but he knew it was powerful and important. At about that time Tony and I went to The Prince of Wales Theatre in Colwyn Bay for a short play festival. Ionesco’s The Bald Prima Donna was watched in incredulous silence until a little woman waving an umbrella stood up to heckle the actors with cries of Rubbish.

A Big Noise from CND HQ in London came up to chair a planning meeting for the forthcoming Tory Conference in Llandudno. I had hired Llandudno’s Council Chamber for the occasion. We even had a march through the town with me up front and I saw myself on TV; the same TV Coronation Street was on.

The plan was to disrupt the Llandudno Tory Conference of 1962. Tony somehow had managed to make contact with Bertrand Russell and he and an associate went to meet him. Russell agreed to write a flyer for us to distribute to the conference attendees. I still have a framed tatty copy, probably the only one extant.

A Message from

Lord Russell to the Delegates

to the Conservative Conference

One of the practices of men in power, who have contempt for their fellow men, is to treat any issue as one of public relations. Cruelty in Africa or idiocy in economic affairs are to be overcome by a few discreet ‘D’ notices to the press and a general line of handouts to other organs of publicity. Failure on the part of the mass media to acquiesce means denial of access to leaks and other favours thrown to the tame by the cynical.

Those who have lost touch with common decency, extend this principal of tawdry rule to matters of life and death. Thus the American and British Governments solemnly proclaim that the high altitude atmospheric tests will have no harmful effects, when every scientist not in Government pay, insists that they will have such effects.

Now the calculated lie is quietly denied, and the five year interruption of the radiation belt, with its concomitant effect on communication is casually admitted. Presumably the fall-out, which has been said by this Government to be of minimal importance, will soon be acknowledged to cause millions of deaths over many generations, with as blasé a display of indifference.

I remind you Conservatives that you have embraced a policy of genocide. You base policy on the willingness to commit mass murder, the incineration of whole peoples. You who speak for this Government should know that all the pious invocation of morality to hide barbarism, will not deceive the people for long.

BERTRAND RUSSELL

Tony had met this bloke who lived over a shop in Rhos. We only knew him as Mr. Hughes. He was probably about fifty which seemed quite old to us. He lived with a couple of East German refugee women who certainly were not old. God knows how he helped them get over the Berlin Wall to Rhos-on-sea. We wondered too about the sleeping arrangements.

Mr Hughes had a plan. We were going to interrupt BBC Television by joining some wires together just before The Epilogue and go live with our own broadcast of the above leaflet which Lord Russell had recorded for us. Pirating radio space was an offence punishable by… well we didn’t really know but Mr Hughes said it would incur a prison sentence if we were caught. It didn’t work anyway so we reverted to the more mundane protest of drawing a man-high CND symbol on a rock overlooking the entry to Llandudno by road. It was a daring climb in the dark but the image remained a landmark for years. It showed we were around. Mr Hughes said an act like this would, Guarantee our place in Heaven; pretty good for an atheist but we all were then. Socialism was probably the nearest we could get to God without actually believing in Him.

There was some alarm for boys of our age with the Bay of Pigs crisis. We had not been required for National Service but now the papers I read as I delivered them around Marine Drive said we might be called up. Bertrand Russell had sent a telegram to Khrushchev pleading for restraint. Much is said about the bravery of Kennedy in this situation but little about the courage it took Khrushchev to back off.

CND and Committee of 100 decided to thank Russell for his contribution to ending this potential global disaster and about a hundred of us arrived in coaches at his home, Plas Penrhyn in Penrhyndeudraeth. The old man was expecting us of course and was brought on to the lawn to meet us by what I imagine today would be called his PA. He was extremely frail and I joked to Tony that a congratulatory slap on the back might be enough to finish him off. In fact he lived for another eight years.

*

Then there was the poetry. We read each other’s stuff and talked about it. I was always a stickler for form whereas Tony adapted a free verse style of which I was unreasonably critical. There was an advertisement in The Observer for a poetry competition. Tony and I both made submissions which got through to publication in Selected Verse 1963 published by Venture Press in Hull.

Tony lived in the cellar of his mum’s B&B and I visited him to find he was not alone. He had followed Mr. Hughes’ example. Two young women from the college were living with him. All three had decided to go freelance with their art, sack the college and form a small commune. Tony was working on a large painting of Jesus I think it was. I visited infrequently because of my sporting commitments.

In the summers cricket dominated my life. Leaving the cricket club late one evening I caught sight of Tony dancing down the street with a much older woman. I guessed it was chucking out time at the Ceilidh Arms. The charming image of the two of them is still vivid and I was reminded of it at the end of the film Michael when Travolta dances in the street with another angel.

News came to me one day that Tony had eloped to Gretna Green with a girl I did not know. I think in those days you could marry there without parental consent if you were under 21. He didn’t get married though and the runaway couple returned to Rhos after two or three days. It made me smile.

So in the summer of 1963 my ‘A’ level exams were over. I had a deal with my mother that I would have a year off then go to university. I had been on a Sorbonne Cours de Vacances in 1962 and wanted to go back to France eventually.

God knows why but I decided to go to Brighton. I had read Brighton Rock after all. It wasn’t long before I had digs. I looked at a room in Clifton Place and was told I could sleep on a mattress on the floor of the bed-sit for ten shillings a week. The bloke I was sharing with seemed OK about it when he appeared later that evening.

Within a couple of days I had got a job at Brighton and Hove Albion, weeding the terraces and painting the bogs. It paid seven quid a week. The manager was Archie Macaulay, a former Scotland and Arsenal player. I befriended his son who occasionally played for the first team. He took me home for Sunday lunch and his mum said she would like me to have at least one proper meal a week at their house. Aren’t people bloody marvellous? I didn’t take her up on it for more than a couple of weeks though as I needed to work seven days if I was going to save enough to get to France.

I took a weekend job at Brighton Palace Pier. I walked around in a brown overall with a chain of keys around my neck, opening machines when they became coin-bound. This paid two quid a day from 11am to 11pm.

One evening I got home to find my flatmate had gone. I phoned Tony to say there was a bed free on the floor if he wanted to come to Brighton. He hitched down a couple of days later. I introduced him to the girls who lived next door, the gay hairdresser from upstairs and a couple of his clients or old dears as he would call them. Tony was immediately at home as I knew he would be.

The football season was due to start and my job at The Albion was coming to an end. There was an advert in The Argus for salesmen so we answered it. Simon came to see us. He was a wealthy middle-aged man, stylishly dressed and had a large, expensive house in Hove. His company sold soap, dusters, demisting cloths and the like door to door and if he employed a few partially sighted people in his factory he could trade as a charity Simon didn’t do any selling himself. He had teams lead by car drivers who got superior commission. We others were the foot soldiers. Our fellow salesmen were mainly out-of-work actors, and a couple of Mods. We got twenty per cent of any money we took. The best seller was a block of eight soaps which cost five shillings. We referred to the job as The Soap.

We used to spend our evenings in the local pubs. One night we were sitting having a chat about poetry, politics or work when this bloke sidled up and said, Which one is the ‘usband and which one’s the wife? A rumpus ensued at this erroneous interpretation of our sexual orientation but we were outnumbered and were dumped outside on the pavement.

I suggested the management at the Pier should take Tony on. They did and we both worked weekends becoming very skilful on the machines. One of the lads who used to work there was due to fly home to Sweden. He came in one Saturday morning to try and win the £12 air fare. It took him all day but he did it. We took a leaf out of his book. The only problem was the weight of the coins in our overall pockets. We devised a plan where instead of taking our breaks we would run back to the bed-sit and dump our booty on the table in the middle of the room. We’d do this four or more times a day. At night we would sit counting the pile like a couple of misers.

The time came when I had got enough money together to leave for France. Tony decided to go back to Rhos. We were very unsentimental about leaving each other, no hugs. Just, I’ll see you when you get back. We were proper friends and absence from each other did not lessen our friendship.

*

Months later, and after many adventures down and out in Paris, I found my way back, and I phoned Tony to tell him I was in England. He said we ought to try Cardiff this time and I was OK with that idea. We agreed to meet a couple of days later.

There was a seriously mis-spelt notice in a newsagent’s window offering a room so we went to see it. It was just a bedroom; well half a bedroom curtained off from the other half. It had a picture of Jesus over the bed and a couple of palm crosses drawing-pinned to the wall. We took it. We removed the decorations and chucked them under the bed which was covered by an old eiderdown. We didn’t explore beneath it. We decided to sleep in our clothes on top of the bedding. We awoke in the dark to the most startling of noises. It was heavy, tortured breathing accompanied by what sounded like the clanking of chains and it scared the shit out of us. The noise gradually subsided into loud snores and it transpired that this cacophony had simply been our curtained neighbour climbing the stairs with his bike.

We left and the next night we had nowhere to sleep. I suggested to Tony we try the police station as I had once before in Woodstock, Oxfordshire when hitch-hiking back from an Aldermaston March.

Cardiff Police Station was very different. They weren’t surprised at our request for accommodation but said we would have to come back later as they were busy. We went back. The interior was more like a prison than a cop shop. There were umpteen cells and we wondered what the detained inmates would have made of our conversation with our friendly warder.

Just pick a cell that suits you. You might want to take two of those mattresses. They are very thin.

Oh thanks this cell will be fine.

I’m afraid I’m going to have to lock you in.

No problem at all and thank you very much.

We found work via the Labour Exchange. The steelworks Powell Duffryn were setting on. They were manufacturing Dempster Dumpsters; refuse trucks of the early 1960’s. Powell Duffryn had owned coal mines until the nationalisation of 1947 when they had to diversify. I got a job in the stores and Tony worked on the shop floor. In my breaks I would drop in to see how he was doing. It was the noisiest place in the world and the noise arrived so randomly Tony would jump every time as though he’d never heard it before.

It was heavy work and we stuck at it for a while. At this time Tony had decided he wanted to be called Antoine or maybe Anton which really went down well with the Cardiff steelworkers. He also insisted on telling our comrades that we were poets which resulted in a few wry grins.

We had our first taste of a strike ballot. We sat on the fire escape steps and viewed the massed heckling throng. The steward addressing the crowd called for a show of hands. We raised ours dutifully. We weren’t even in a union but whatever these men wanted from their bosses was OK with us.

Tony came home one evening to tell me he had fallen in love with Cardiff-born Janice Morgan. He said she looked like a painting from the Italian Renaissance and when I met Janice I agreed with him. I learned later that her mother had at first been alarmed by Antoine both in terms of his new-age appearance, his uncertain social circumstances and his earning power. She was soon won round by his charm and the fact that he decorated her living room.

*

It wasn’t long after that we left Powell Duffryn and went on the dole. I’m not sure why. I guess we’d realised we weren’t really steelworkers after all. To sign on was a complete bore. We’d spend all day waiting to be seen and eventually we’d be given a few pounds cash or National Assistance as it was then. After that we had to stand in a queue once a week to sign for our money.

You always had to sign on the same day each week. I wanted to go back to North Wales to collect some stuff and Tony said he would come with me. We went to sign on a day early and I told them I had to see my grandmother the next day. The guy was refusing our request when Tony leapt in with, She’s dying.

The clerk stamped our cards and handed over the money. Both my grandmothers were dead before I was born, incidentally.

We always went straight from the Labour Exchange to buy essential supplies for the week. Top of the list was tobacco which was ten bob for a tin of Sweet Virginia and our roll-ups generally lasted for about five days. We’d also buy beer for the first day or so.

Whilst on the subject of smoking I recall that Tony switched to smoking St Bruno Flake which was pipe tobacco, only he smoked it in rolling papers. From this extreme smoking he went cold turkey in about 1965 and to make sure he didn’t renege on his resolution he harangued his local newsagent on the evil of selling this poison to the general public. He didn’t feel he could buy tobacco there after that; probably a better solution than patches or today’s e-fags.

Although it was the Sixties we were not part of the drug culture but dabbled. We were in a café once at Cardiff bus station when Tony said he had some Benzedrine which he took in a small paper screw like the salt in the old Smiths’ Crisps. It made him sweat. It was supposed to have an euphoric effect but it brought on Tony’s prickly heat which he had picked up in the Merchant Navy. He ripped his shirt off and walked bare-chested through the shoppers in wintry Cardiff.

Another time – it must have been when we were living in Rhos – Tony had news of a squat in Ladbroke Grove where anyone could just turn up and doss. We went down to London, found the house and entered. An Indian guy was sitting on a table in the middle of the first room smoking a spliff. He declined any conversation but waved a gentle welcome. We didn’t stay but Tony managed to acquire a small block of hashish from one of the residents.

We went to Soho. Tony shaved a bit of the block into our normal roll-ups and we smoked as we walked the streets. Tony put “It Ain’t Me, Babe” on the juke box in a pub. It was the first time I had ever heard Bob Dylan and I was captivated. I’d swear the dope had no effect on me but then I can’t remember where we spent the night or how we got back to North Wales.

Back in Cardiff, Tony was spending more time with Janice and I would sit in my sleeping bag reading or writing. The gas would have run out before the next pay day but the small ring would never completely extinguish and I would suspend my feet over it to combat the freezer that was our room. I got chilblains. Towards the end of our pay week Tony and Janice would bring me food from her mother’s larder. It was a bleak time and I decided to hitch home to Llysfaen where my mother now lived and spend Christmas with her.

Tony always said if he were to marry it would be a quick, private ceremony with no guests and that is what he did in 1965, six or so years later. Janice Morgan and Tony were married in a Cardiff register office with only my former wife Karen and me present. Their son Dorian was born later the same year.

*

Tony was best man at my wedding as I had been for his. He had given us one of his paintings as a wedding present, too. It was based on Munch’s The Scream. He had handed it over rather reluctantly and whenever he visited he would say it needed more work. In the end we gave it back to him.

At the end of the summer Karen went back to her parents and I returned to Cardiff to find a flat. I hired a van and Tony, who was living in Cardiff at Janice’s mum’s, came with me to collect our rudimentary furniture from Worcester Park and install it at our Kimberley Road address. We drove the van into Tiger Bay to get some cheap dinner. Outside the café a prostitute was leaning in and out of car windows talking to potential punters. Tony went out and spent half an hour or so talking to her in the street. You couldn’t stop him socialising. Tony was genuinely interested in pretty much everyone.

He told me that he had been to see R. S. Thomas. He just marched up to his rectory, knocked on the door and introduced himself as a fellow poet. Thomas had invited him in. He befriended Cicely Hey who had been a model for Walter Sickert and was a member of the Bloomsbury Set. She was in her eighties. Tony would visit her regularly. She was producing her own sculptures by then.

Around the autumn of 1966 Tony approached The Welsh Arts Council for advice on how best to launch himself as a painter. They suggested he should take up a bursary at Coleg Harlech and that’s what he did. He commuted from Old Colwyn and spent the weekdays in residence at Harlech. He didn’t enjoy the experience however and only stuck it out for about a year.

In the spring of 1967 examinations were over and we spent the summer in Llysfaen where I met Danny who was a linesman. Linesmen supplied the cables to the newly erected pylons across North Wales. One day he asked if I could drive a lorry. I said I thought I probably could. He gave me a test, driving round the lanes of Llysfaen. It was terrifying and I was over steering the three ton Bedford. He seemed to think I had done OK and introduced me to his employers AEI Cables as a lorry driver. Within a few days I was driving a gang out to the site, three of them in the cab and the rest under one of those yellow plastic huts on the back of the lorry.

The Gobles were living in a flat in Old Colwyn and Tony had decided to reach out to local writers and artists through an advertisement in The North Wales Weekly News. There was to be a meeting and I attended. There were six or seven of us in the living room when the doorbell rang and Tony disappeared for about half an hour. He came back into the room to say another poet had arrived but didn’t want to leave the kitchen.

I went into the kitchen to find Frederick sitting on the gas stove, head bowed and adorned by a baseball cap. He spoke slowly with a Canadian accent. He lived in a tiny caravan in a remote part of Snowdonia and he was depressed which didn’t surprise us. He rode an old motor bike. He hadn’t got any poems to show us as they were in the caravan.

I don’t know how we got there but we did visit Frederick. He had a small printing press and had beautifully and painstakingly reproduced his poems on to high quality vellum. The printed poems contrasted markedly with the dishevelled poet, like Baudelaire’s swan in walking and swimming modes. The surrounding mountain ridges looked indignantly down from the mist on Frederick’s humble, scruffy abode.

Frederick came around quite a lot. He came to visit me once at my mother’s house on the top of Llysfaen. His motorbike had broken down at the bottom of the hill and he had walked up to tell me. I had to help him shove the bloody thing up Ffordd-y-Llan so we could repair it in the garden.

The first time the three of us went out for a beer was in the Ceilidh Arms where my Dad had drunk in the 1940’s. Tony had to educate Frederick on the etiquette of buying his round. His insistence finally paid off and Frederick went to the bar.

Tony had various schemes to earn money. I almost remember him being a sea lion trainer and a pig farmer but that might be resonance from the obituary I read. He once told me of his exploits in the landscape gardening arena. He took on too much work and the only available personnel he could call on were the monosyllabic – in public anyway – Frederick and a local lad who was narcoleptic. So Tony was the only one who could communicate with the customers and ended up sweating with the mower whilst his staff slept on the compost heap or sat morosely on the garden wall.

He worked at a diamond tool factory and he was the best the company ever had at using the implements. Sometimes he would turn up to work and say he wasn’t in the right frame of mind for using the cutting tools. His boss would let him go home. Tony said it would save him money in the long run as buggering up was costly.

Tony and Janice had bought a house in Llanfairfechan and I asked Danny if I could borrow the Bedford lorry one weekend to move them. It was like a scene from The Darling Buds of May as the six of us including the two little boys pulled up with all their chattels; the most precious of which were tucked away in the plastic hut. There was a low stone wall opposite their house and I managed not to see it and put a dent in the wheel arch. Danny made quite a fuss about it when I got back.

We made several trips to Llanfairfechan over the next few months. There is a tunnel on the road and people thought it fun to hear the exaggerated echo when they beeped their horns. This used to drive Tony mad. He had a moped or motorbike and although he knew the beeping was inevitable he would always jump and curse just as he had done at Powell Duffryn Steelworks.

We walked in the hills around the coast and I remember coming across the thrilling sight of a herd of wild ponies. I’ve only ever seen them once since, on Conwy Mountain years later with my wife Janet.

The next few years, after graduating from Cardiff University, took me and my young family around the country, and I eventually became a teacher at Dudley Grammar School.

In 1971 I was appointed Second in Department at Alumwell Comprehensive School in Walsall. Teachers had a decent pay rise under the Clegg Review and we were able to get a mortgage on a house in Penkridge, Staffordshire for about two grand and a new Minivan. Two years later we bought at auction a cottage in Hyde Lea, Stafford.

We visited Tony and Janice in their house in Old Colwyn but there was nobody home. I called in at the local betting office and was surprised to find Tony there. That was my territory after all. That may well have been the last time I saw him.