It’s that time of year again, and Wales Arts Reviews‘ writers have been choosing their cultural highlight of the year. The brief was simple, it had to be something that happened in 2013 and it had to be something that left a mark on that writer’s psyche. In three parts, we see impassioned writing on a diverse range of subjects, and also see the emergence of a striking cultural map of 2013. Part One takes in topics that include World Record Day, a Zombie invasion of North Wales and the energetic exploits of a post-punk drummer.

Craig Austin

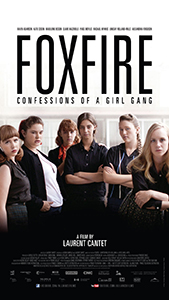

Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang

Foxfire plays to so many of my personal cultural fetishes that I’ve taken to wondering about the likelihood of it having been subject to a uniquely rigorous pre-release test screening; an audience constituted solely of me. Well, maybe me, Morrissey, and Julie Burchill, but definitely no one else. Its cumulative layers of teenage gang culture, 50s Americana, ill-informed flirtations with Communism, and thrillingly unfocused militant feminist agit-prop, always suggested that it was likely to be my nailed-on film of the year before I’d even seen it. I’ve since watched it three times. It is.

Foxfire plays to so many of my personal cultural fetishes that I’ve taken to wondering about the likelihood of it having been subject to a uniquely rigorous pre-release test screening; an audience constituted solely of me. Well, maybe me, Morrissey, and Julie Burchill, but definitely no one else. Its cumulative layers of teenage gang culture, 50s Americana, ill-informed flirtations with Communism, and thrillingly unfocused militant feminist agit-prop, always suggested that it was likely to be my nailed-on film of the year before I’d even seen it. I’ve since watched it three times. It is.

Being a more faithful adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ source material than the earlier, weaker, 1996 adaptation featuring Angelina Jolie, Cantet conversely assembles an ensemble of mostly non-professional actors to bring to life his own account of this mid-50s working class blood sisterhood; the notion of Firefox itself being a violent reaction against the bullies, predators and (almost exclusively male) assholes of their suburban upstate New York existence. As the self-styled outlaw gang’s de facto leader, Raven Adamson – the film’s real discovery – steals the show in her portrayal of Legs, a single-minded fireball of impassioned idealism and knee-jerk confrontation. A benevolent dictator imbued with Gatsby-esque means of inspiring loyalty and awe.

From small acts of suburban rebellion and gratifying revenge, the gang progresses to crimes more complex and brooding in nature; a passage that culminates in a singularly alarming act borne of financial desperation and class-hatred that tears apart the lives and friendships of its members. It’s a film that’s been lazily compared to period teen dramas such as Stand By Me and The Outsiders, but that seems to miss the point entirely. For me it’s a film that starts off as Carrie, morphs into Heathers, and concludes as The Baader Meinhof Complex. And, from me at least, praise doesn’t get any higher than that.

Graham Tomlinson

Enjoy the Experience: Homemade Records 1958-1992

If you spent Saturday 20 April 2013 hanging around your local record shop in support of Record Store Day, you may have seen or even bought a copy of Enjoy The Experience: Homemade Records 1958-1992 (Sinecure), edited by Johan Kugelberg, Michael P Daley and Paul Major. This beautiful large-format hardback gathers together stories and cover scans of hundreds of privately-pressed LPs from the USA. Open it at random and you’ll be presented with a confounding selection of haircuts, teeth and ill-advised outfits, often presented with compellingly poor design work, but captured forever on flimsy cardboard. An album compiled to accompany the book allowed us to enjoy what the authors call the ‘sincerity and vulnerability’ of just some of those acts who pursued their obsession to the ultimate end: a record with their name on it. By sheer good fortune, I was in New York in July when the exhibition accompanying both book and album was on at the Milk Gallery in Chelsea. The walls of the gallery were covered with huge displays of the sleeves featured in the book, but best of all, visitors were able to thumb through racks of the original records and listen to them on a pair of decks set up for the purpose. I spent a very happy couple of hours gazing at the displays and comparing rival showband versions of ‘Long Train Runnin’, delighted in equal measure by the single-mindedness of the performers and by the eccentric obsessiveness of the project’s curators. A splendid one-off.

Steph Power

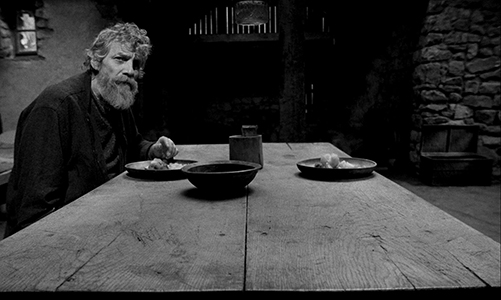

The Turin Horse

I’m not sure how it happened, but it’s taken me two years to get around to seeing Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr’s magnificent last release The Turin Horse (co-directed by Ágnes Hranitzky). I suppose you could argue that glacial slowness is such a feature of Tarr’s oeuvre that this might be in keeping with his spirit. Except that that’s the kind of romantic guff that’s entirely absent from Tarr’s bleak and grainy portrait of the end of days.

I’m not sure how it happened, but it’s taken me two years to get around to seeing Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr’s magnificent last release The Turin Horse (co-directed by Ágnes Hranitzky). I suppose you could argue that glacial slowness is such a feature of Tarr’s oeuvre that this might be in keeping with his spirit. Except that that’s the kind of romantic guff that’s entirely absent from Tarr’s bleak and grainy portrait of the end of days.

The film imagines the life of the so-called Turin horse, and the owner who flogged it so unmercifully on a street in 1889 that the onlooking philosopher Friedrich Nieztsche is said to have been propelled into madness and eventual death by the sight. There’s no violence in the film, however, but the stark, repetitive, droning despair of daily life for people living in abject rural poverty. All shot in black and white, with barely any dialogue, and using just thirty long, long takes.

A gale blows without end in a Central European wasteland. Two occupants of an isolated farm tend to their horse, fetch water, chop wood and stare out the window. They are, it seems, a father and daughter, though more about their identity we never learn. In effect, they are humanity; as boiled down to its grim, flavourless essence as the potatoes they unendingly eat. Gradually, the horse refuses to work or feed, and news comes of an approaching apocalypse. Again, what this is we never learn, but the inference is that it is not so much the death of God in a Nietzschean sense, as the destruction of the world brought about by man and some higher force together.

If this sounds dismal, you’re right – it is. But the paradoxical combination of sheer, claustrophobic depth of focus and expansion – as in all Tarr’s mature work (like the epic Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies) – makes for compelling viewing. His unflinching portrayal of the dogged will to survive makes the ordinary extraordinary and locates a profound, disturbing beauty in an amoral universe that is both real and otherworldly. Central to the film’s elemental power is its rough, trance-like score by Tarr’s long-time musical collaborator, Mihály Víg. A simple melodic phrase is repeated ad nauseum against the singing of the wind, embodying the stony coldness of the terrain both physical and metaphorical. In other words, the film is not so much intended to be pondered over as listened to. And, in the listening comes a profound peace; not the passivity of servile acceptance but rather a strength of understanding that lies beneath the endless struggle of existence.

In short, The Turin Horse is the work of a cinematic genius – and Tarr, who has given up filmmaking himself in his late fifties to open a film school in Croatia, has vowed that it will be his final film. Damn.

Dylan Moore

the promo video for ‘Rewind the Film’

Such is the mythological power of Manic Street Preachers – music, image, text –that the band can sometimes be seen as a self-contained rock’n’roll fantasy, rather than part of the socially engaged reality to which they always aspire. The fact that they were able to give the appellation National Treasures to their 2011 singles collection is indicative of the kind of band they have become, and there is no doubting the nation to whom the Manics belong. But detractors might claim that from 1998’s This is My Truth, Tell Me Yours on, the band have made music more akin to Wales’ national wallpaper than deserving of a place at the hearth.

However. This year’s long-player Rewind the Film, with its intense atmosphere of acoustic introspection and tales of class war, is destined to become a key touchstone in the band’s already classic canon. Its opener, ‘This Sullen Welsh Heart’ features the gorgeous vocals of the 23-year-old Warwickshire nu-folk songstress Lucy Rose and the lyric, as well as stripping bare Nicky Wire’s middle-aged vulnerabilities, reveals something in the band’s DNA, infinitely sad and unmistakably Welsh: ‘This sullen Welsh heart / it won’t leave, it won’t give up / the hating half of me / has won the battle easily…’

The same melancholy is captured in my choice of artistic moment of the year: the opening sequence of the promo video for the album’s title track. I defy anybody familiar with the people, landscape and atmosphere of South Wales to watch it and not be moved. First, shafts of sunlight break through the clouds, then a series of stills show the remaining rust-painted pitheads against a backdrop of hillside forestry plantations. A tattered red dragon flutters in the breeze and we see familiar terraces before learning that this is Colliery Street, and a version of Memory Lane.

As we follow a retired miner through the familiar scarred post-industrial landscape, the mix of nostalgia and sadness is almost unbearable. Empty chairs, empty rugby field, boarded up buildings; signifiers of a broken community. The music is faintly reminiscent of Elvis or Johnny Cash; all the while, the weary tones of Richard Hawley intone a litany of resignation. ‘I want to feel small / Lying in my mother’s arms / Playing my old records / Hoping that they never stop’.

Then, at 3:12 in the video, the exact midpoint of the song, James Dean Bradfield lets rip. As there has always been, there is an honesty and righteous rage to both the lyrics and Bradfield’s searing vocal: ‘I want the world to see all the love / And security, my childhood dreams / But now I am just broken flesh /And I am waiting for the night to come’. Behind our protagonist, a wall is dedicated to those from the community killed in action for their country, paper poppies and Union Jack bunting draped ingloriously over their fading photographs. Against this backdrop, the weekly game of bingo plays itself out emotionlessly. Elderly women sup from pint glasses of beer, hands bedecked in jewellery while numbers flicker on a pitiful screen; ‘Good Luck’, it says.

As the song draws to a close, dusk settles over the valleys, car headlamps and streetlights busily skittering into the darkness. The film finishes with a series of faces, head-on, staring straight into the camera, each of them dewy-eyed with nostalgia and regret. Our man turns the lights off in the club and heads out, into the darkness.

Sarah Rhoslyn-Moore

Zombies from Ireland

Zombies From Ireland has to be the highlight of the year for me; truly inspiring, young people taking charge of their destiny and making things happen for themselves, social network communication at its finest, funding issues diminished. Where there is a will there’s always a way!

The blood was convincing and the sound effects were good, actors varied in acting ability and sexualisation of women were evident: all the ingredients needed for a typical zombie movie. When you take into consideration that this is a non-funded first film, filmed on an ordinary home video camera, and how the director managed to get young people involved in creating something, Ryan Kift comes out of it as a truly inspiring emerging director with his creative imagination and his attitude towards pushing boundaries. Amongst these radical young people of North Wales was an older woman in her sixties, a first time actress, Penny Davies, who supported and got involved with the young crew. She was the first to be eaten by a Zombie. She also stands out with her convincing Zombie acting. When asked in the QnA that followed the premier what was her favourite part she replied, ‘When I was screaming my head off’.

The spirit of the crew came through in that QnA. They clearly had fun and were enjoying every bit of their success. The creation of the film is an important part of the story. Casting relied solely on Facebook, Kift offering a first come first served opportunity for anyone with an interest in becoming a Zombie. The iconic scene of the hundred or so Zombies walking across the Menai Bridge is the highlight. Strangers gathered at 3am to take part. A reason Kift gave as to why so many people turned up at this hour was that, ‘It must be really shit around here (Gwynedd) and people have no money, they turned up because they had nothing better to do.’

Gary Raymond

Fay Milton, Drummer for Savages

‘Imagine a man brought up from birth in a white cell so that he has never seen anything except the growth of his own body. And then imagine that suddenly he is given some sticks and bright paints. If he were a man with an innate sense of balance and colour harmony, he would then, I think, cover the white walls of his cell as [Jackson] Pollock painted his canvases. He would want to express his ideas and feelings about growth, time, energy, death, but he would lack any vocabulary of seen or remembered visual images with which to do so. He would have nothing more than the gestures he could discover through the act of applying his coloured marks to his white walls. These gestures might be passionate and frenzied but to us they could mean no more than the tragic spectacle of a deaf mute trying to talk.’ So wrote John Berger in his critical essay on the work of the iconic American painter. And in November 2013, it was a passage that rolled through my mind as I watched Fay Milton drumming for Savages.

‘Imagine a man brought up from birth in a white cell so that he has never seen anything except the growth of his own body. And then imagine that suddenly he is given some sticks and bright paints. If he were a man with an innate sense of balance and colour harmony, he would then, I think, cover the white walls of his cell as [Jackson] Pollock painted his canvases. He would want to express his ideas and feelings about growth, time, energy, death, but he would lack any vocabulary of seen or remembered visual images with which to do so. He would have nothing more than the gestures he could discover through the act of applying his coloured marks to his white walls. These gestures might be passionate and frenzied but to us they could mean no more than the tragic spectacle of a deaf mute trying to talk.’ So wrote John Berger in his critical essay on the work of the iconic American painter. And in November 2013, it was a passage that rolled through my mind as I watched Fay Milton drumming for Savages.

It was a mini-Wales Arts Review outing. I went with Dean Lewis and Craig Austin to Bristol’s Trinity Centre, a cold cave of a building with an Eastern-Bloc feel that complimented the greyscale aesthetic of the band very well. They delivered their version of post-punk Siouxie Sioux swaggering with a winning charm, but the gig was entirely about the woman at the back. Savages songs hang on her iron frameworks; they nomadically set up camp, burn the soil around them and move on, as forceful and dynamic as they are nimble and… well… savage. Most tracks career through right angles of mismatched beats, and Milton, at times, resembles a woodcutter, an Olympian carpenter trying to create beauty and subtlety deep in the unhelpful belly of Hephaestus’ mountain iron forge. She is always putting out fires, honing the landscape of the song, corralling what is left into a viscerally beautiful frame.

I have never spent an entire gig staring at the drummer before (and neither had Dean Lewis, he informed me after the event, when the hipsters were packing their iPads away and the Red Stripe cans were being swept up). That Savages are such a tight package, such a carefully chiselled aesthetic unit, only emphasises just how mesmerising Milton was. If profundity can be found in the grace employed in animalistic power, then that is what she was that evening. As the reverberation of the skins juddered and thuddered through the hall, down the walls and up through the floors, cliché upon cliché came through me, clichés of tribalism and primeval connections, how a modern sound can drag your atoms back to a time when the universe began. But Berger’s words on Pollock say it better. What is a drummer if not a ‘deaf mute trying to talk’, the conveyance of passion and frenzy through the last gasp of the human experience; the physical being? Fay Milton’s performance is my cultural highlight of 2013, because it was like a great and exhausting conversation, between the two of us, fluent in a language I had not learned, teaching me lessons about love and time and space. Now, that’s not a bad night out.

Go to Wales Arts Review Highlights of 2013 Part Two

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis