St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 16th November 2012

Mozart: Masonic Funeral Music

Henze: Movements from the Requiem: Introitus / Agnus Dei / Sanctus

Mozart: Requiem

Conductor: Christoph Poppen

Soprano: Elizabeth Watts / Mezzo: Máire Flavin / Tenor: Andrew Tortise / Bass baritone: Gary Griffiths / Trumpet: Dean Wright / Piano: Simon Phillippo

When tonight’s concert programme was devised months ago, there could have been no inkling how prescient it would turn out to be with the death, on October 27th, of Hans Werner Henze at the age of 86. At once, an early appetizer to Welsh National Opera’s forthcoming Spring 2014 production of Henze’s opera Boulevard Solitude (1952) became a poignant memorial to a leading composer of the late Twentieth Century – and one of the most important to have emerged from the ashes of Hitler’s Germany.

In his 1998 autobiography, Bohemian Fifths, Henze described hearing Mozart on the radio as an adolescent, traumatised by Nazi brutality, in words that encapsulate what he himself went on to aspire to as a composer and a man:

‘It seemed to me as though here was a composer who, lovingly and knowingly, had evolved beyond the music that typified his time and country … Against the cultural background of his age, Mozart opened up a whole new world of emotion in which … feelings such as femininity and desire, tenderness and love … are just as important as frivolousness and danger, risk-taking, death and despair in the form of aggression and masculinity … It is music of and for humanity.’

Indeed, he wrote that:

‘My goal was Mozart, beauty, perfection, a new form of truth – a truth that pays no heed to the Zeitgeist and that triumphs over death itself’.

How far Henze achieved his loftier artistic ambitions remains open to question, but his life-long social and political commitment and sheer maverick endeavour are demonstrable; tonight’s moving rendition of three sections from his Requiem felt especially apposite alongside a refreshingly spirited Mozart’s, whose seminal final statement was, of course, left unfinished upon that composer’s untimely death in 1791 aged just 35 (not to mention unsatisfyingly – if quickly – completed by his pupil Franz Süssmayr).

and tragic last days, have famously been subject to all

sorts of romantic speculation of the fictional variety”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

January 27 1756 – 5 December 1791

Perhaps now, as we emerge from a period of de-politicised post-modernism – in which notions of truth seemed to get submerged to an unhealthy degree by relativist equivocation – Henze’s more polemically abrasive, overtly left-wing music might stand reappraisal. At any rate, the luminous performance here tonight demonstrated the emotional power of which he was capable in more lyrical mode, without forsaking the opportunity for direct social allusion. Choosing to omit the Latin text in favour of solo instrumentalists for a series of nine ‘sacred concertos’ (and reordering the liturgical sequence), the unreligious Henze nonetheless intended his Requiem to stand not only as a secular ‘act of brotherly love’ for Michael Vyner, erstwhile Artistic Director of the London Sinfonietta, but ‘for all the many other people in the world who have died before their time’ and as a paene for human suffering. In its entirety, the work is overlong and texturally unrelenting without compensating clear direction, but the combination here of opening and closing Introitus and Sanctus with the sixth movement Agnus Dei opened an, at times, exquisite window on his intensely felt musical world. Special praise must go to conductor Poppen and the superbly evocative soloists Simon Phillipo and Dean Wright, as well as the echoing trumpeters placed in the auditorium.

If Henze was a latter-day romantic who took pains to deny his romanticism, the story of Mozart’s Requiem, his short life and tragic last days, have famously been subject to all sorts of romantic speculation of the fictional variety. Thankfully, tonight’s performance did not, as can so often happen, over-milk the pathos (nor did it – as Richard Taruskin has so eloquently noted of many a supposed “authentic” performance – ‘embalm [Mozart] in “historical” timbres’); instead, Poppen and his committed ensemble succeeded in demonstrating the work’s undoubted power through clear and thoughtfully-modulated enthusiasm rather than a straining towards the mythic or unduly mystical.

Having come to symbolise the painful quenching of young genius in popular imagination, the Requiem itself, retrospectively – and more prosaically – looks back to older, Baroque settings of the Latin mass, whilst opening the way to newer, more operatic approaches to liturgical form; that said, it is a largely choral work and, of tonight’s soloists, it was the soprano alone, Elizabeth Watts, who took true expressive flight. The chorus themselves were mostly magnificent and sang with gusto, albeit with lower voices veering towards harshness in some louder passages such as the opening of the Rex tremendae.

Both tonight’s composers were preoccupied by death at times – as are we all necessarily. More importantly, they both actively sought the artistic freedom without which life itself can fall into the metaphoric but by no means petty deaths of inertia and apathy. Mozart’s loosely freethinking Catholicism was supplemented by a (yet) more mysterious commitment to brotherhood in the form of Freemasonry; a connection which inspired the brief but intense Masonic Funeral Music in memory of two dead brethren, and which proved an excellent introduction tonight.

form of truth – a truth that pays no heed to the

Zeitgeist and that triumphs over death itself”

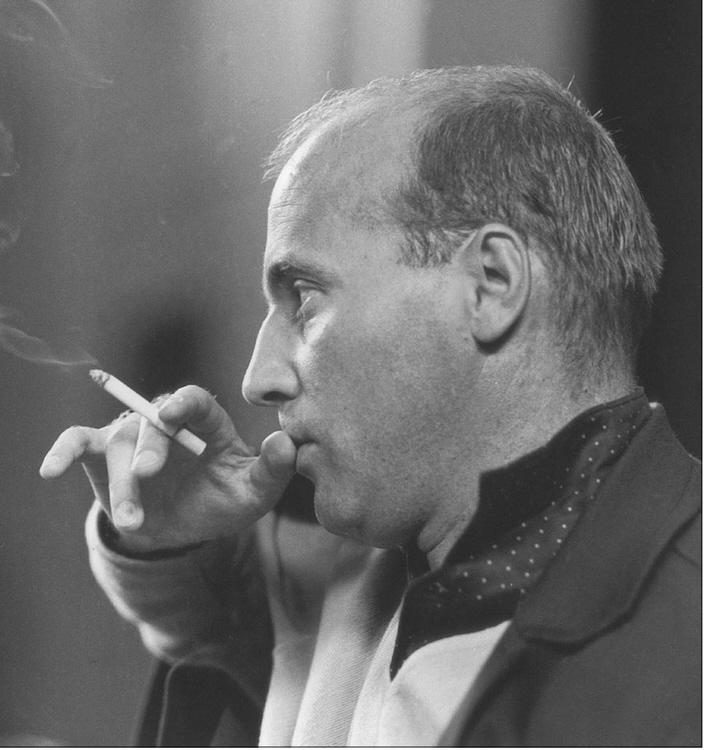

– Hans Werner Henze

1 July 1926 – 27 October 2012

Henze swam perhaps more obviously against contemporary prevailing tides with his open homosexuality and Marxism; exiling himself not only from his German homeland in horror at war atrocities, but musically, post-war, against what he quickly construed as an authoritarian modernist orthodoxy, epitomised by hard-line peers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez. Despite later returning as a prodigal son to Germany to work, he never quite managed to reconcile himself on political grounds to being the natural successor of a German tradition stretching back to Mozart and beyond. Time will tell if upholders of that tradition will embrace him – that is, to the limited extent they embrace any post-war composer – by continuing to programme his vast body of works in familiar genres; from symphonies and ballets, to operas, string quartets, chamber and vocal music – and, indeed, his Requiem.