Welcome to Wales Arts Review’s new series ’10 in 10′. Every week for the next 10 weeks we’ll be publishing a list featuring 10 entries which link to key cultural moments in contemporary Wales. We kick off our series with a look at 10 cultural moments that defined contemporary Wales, from the establishment of the Iris Prize, to the U-turn on the Flint Ring, these are 10 of the (post-devolution) moments which helped to shape contemporary Wales.

Founding of National Theatre Wales

The English language national theatre company for Wales was founded in 2009 by a passionate conglomerate of powerbrokers who, inspired by devolution, felt a confident new nation deserved a confident new production company that would encapsulate and project the mood, passions, and idiosyncrasies of the people of Wales. John McGrath was Artistic Director for the first ten years, and brought a distinct ethos to the operation. NTW was to be an innovative, progressive, dazzling theatre company more in the European tradition of site-specific development rather than the English tradition of written plays on a stage. In its first year, it produced thirteen ambitious shows around Wales, creating enthusiasm for the collective vision everywhere it went.

Commissioning of the Library of Wales

A few years into the new millennium, the Welsh Books Council (as it was then) put out a tender for the publication of a new series of classic Welsh writing, to be called Library of Wales. Parthian Books won the bid and in 2006 the first of fifty titles of great Welsh books was launched with Raymond Williams’ Border Country. The only stipulation to qualify for this new series was that the book must be out of print. Over the following years, the library reintroduced some books that have since been reappraised as essential texts in the story of our national literature, and to look back at some of the books on the list it is astonishing so many of them were ever out of print, such staples of the Welsh canon they seem now. Border Country, Ron Berry’s So Long, Hector Bebb, Dannie Abse’s Ash on A Young Man’s Sleeve, and Margiad Evans’ A Country Dance to name but a few. As the fiftieth came closer to release, series editor Dai Smith came under some criticism for how thin on the ground women writers were, but even this criticism helped us as a country address the wider implications of inequality in our literature. The Library of Wales has served us so well in so many ways.

Building of the Wales Millennium Centre

Controversial for a number of reasons when it was first mooted in 1995, the building that was to become the Wales Millennium Centre is yet another example of a newly devolved nation announcing itself on the European stage. Built to be a huge cultural hub, it may not have always fulfilled that ambition, but it’s still there to be that if just handled right in future. As it is, the WMC is nowadays not just an iconic sight on the Cardiff Bay skyline, but it is a vital part of the cultural ecosystem of Wales, as home to national companies (including the Arts Council of Wales, National Dance Company Wales, Literature Wales, Ty Cerdd, and others), and as a production house in its own right. Although it must not be forgotten what was lost in its construction (memorialised so viscerally in the mural of the conference room in the nearby Bute Town Community Centre), it is now difficult to imagine Cardiff Bay without it, the giant armadillo without those wonderful words of then National Poet of Wales Gwyneth Lewis carved into its shell, CREU GWIR FEL GWYDR O FFWRNAIS AWEN/IN THESE STONES HORIZONS SING.

Dr Who comes to Cardiff

So the story goes, part of the deal struck between Russel T Davies and the BBC back in 2003 to have Davies resurrect the Dr Who franchise and present it for a new generation of kids starved of quality British sci-fi was that the production would be based in Wales. If it was a powerful gesture from Davies to his homeland that would see jobs flood in for this blockbuster production, it cannot be overstated how much the legacy of that deal has had a long term effect on what Wales means to BBC television drama nowadays. Dr Who’s location in Cardiff created an industry that before that was little more than a satellite for Casualty filmed in Bristol. And in an exciting turn of events, in 2023, as Russell T Davies returns to the helm, he comes back to a TV landscape now firmly in the big league under the wing of Julie Gardner and Jane Tranter’s stratospherically successful company Bad Wolf. The company may have taken its name from a motif in Dr Who during Davies’ first stint as series leader, but it’s since gone on to create global hits such as The Night of (which won five Emmys), His Dark Materials, and Discovery of Witches.

U-Turn on the Flint Ring

If many of the selections on this list speak of a new nation expressing its confidence through its cultural might, then the fiasco over the proposed public art of the Iron Rings of Flintshire shows a nation no longer willing to be treated with disdain by the people in charge. A non-starter for almost everybody who witnessed the announcement, the enormous Iron sculptures would memorialise the ring of castles King Edward II built in order to supress the Welsh people. You can read more about the whole thing in Adam Somerset’s account of it for Wales Arts Review in 2017.

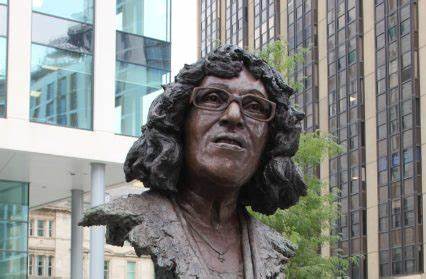

Amazing to think that until 2021 you would not find a single statue in Wales dedicated to an actual real-life woman. The colossal efforts of an organisation called Monumental Welsh Women changed that, and after a public vote from a shortlist, Cardiff teacher and local hero Betty Campbell was announced as (hopefully) the first of many to be erected across the country to add some balance to all the statues of male politicians and landed gentry. You can read an in-depth review of Eve Shepherd’s sculpture in this piece for Wales Arts Review by Gary Raymond.

Establishment of a National Poet

Yet another statement of a confident new nation, in 2005 Academi (later to become Literature Wales) established the role of the National Poet of Wales, a laureateship that was to carry with it the responsibilities of expressing a voice that encapsulates a national mood at times of note. The National Poet would be called upon to put a stamp on things. Inaugural poet, Gwyneth Lewis (2005-2006) did just that when she wrote the words that stand six feet high still on the Wales Millennium Centre. She was followed by Gwyn Thomas (2006-2008), Gillian Clarke (2006-2016), Ifor ap Glyn (2016-2022), and now, with a three year tenure, Hanan Issa took the reins in 2022. The national poet is not just a writer of apposite verse, but is a symbol of the ethos that appointed them, and is there to represent the country in all of its complexities. A dizzying role for anyone, but a vital position for the land of the bard.

The Iris Prize

The Iris Prize and accompanying festival was established out of Cardiff in 2007 by Berwyn Rowlands. It is now an internationally renowned LGBT+ film festival that enjoys entries from Indonesia to Iceland, celebrating and exploring as wide a parade of life experiences as you could possibly imagine. The festival runs over many days (this year it’s six days across a range of cinemas), and partners with a raft of gay and lesbian festivals around the world. The prize itself, which includes awards for best international short, best of British, awards for actors and awards handed out by a jury of young filmmakers, hands out £30,000 in prize money, the most of any gay and lesbian film prize in the world.

The Establishment of Firefly Press

There are few tougher industries than the world of independent publishing, but Firefly, Wales’s first book publisher dedicated entirely to writing for children and young adults, have at times made it look easy. Established in 2013 by Penny Thomas and Janet Thomas, Firefly has quietly gone about changing the landscape of Welsh publishing for younger readers, bringing out a list of books by authors with wit and vision to spare. They have also bagged major awards, including a prestigious Branford Bosse Award in 2016 given out to author and editor, given to Penny Thomas and Horatio Clare for his book Aubrey and the Terrible Yoot, about a young boy dealing with his father’s depression. Firefly continues to go from strength to strength and never fails to show bold and creative decision-making in its lists. They recently brought out the English translation of Manon Steffan Ros’s Welsh language sensation The Blue Book of Nebo, and it’s proving just as successful in English.

Cardiff Eisteddfod

The 2018 Eisteddfod was revolutionary in its way, and was praised by many as the most diverse ever held. Chair of the Organising Committee Ashok Ahir envisioned a festival without fences and without ticketing, and the layout of Cardiff Bay provided the perfect landscape for the Eisteddfod to fulfil these ambitions. At the time, Ahir said he hoped for Cardiff Bay to host it every five years, as a symbol to Wales and the world that the Eisteddfod was a celebration of the Welsh language and Welsh language culture for the everyone to enjoy. It was, by most measurements, a huge success, and many came away feeling exactly as Ahir would have wanted. As with so many things, Covid may have put a spanner in the works of any plans to bring the Eisteddfod back to Cardiff within five years, but there is no doubt that the outward looking, all-embracing Cardiff Eisteddfod of 2018 changed many perceptions of this age-old festival, and for many modernised it for the better and for good.