Craig Austin reviews Jon Savage’s 1966: The Year The Decade Exploded, pinpointing the artistic and political eruption of 1966.

In Steven Soderbergh’s tremendous 1999 noveau-noir The Limey, Peter Fonda’s character Terry Valentine reflects wistfully upon the cultural and social impact of the 1960s while aggressively flossing between his Californian teeth in the bathroom of a grandiose LA mansion. As his wide-eyed young lover listens intently to these tales of ‘one golden moment’, Valentine extols the magical virtues of a time and a place ‘that maybe only exists in your imagination, some place far away, half remembered’. This of course is the unchallenged received wisdom that clings to the notion of the 60s as tightly as a cheap Carnaby Street suit. A fleeting gilded existence in which the hair grew longer as the skirts got shorter, a period that subsequently succeeded in defining itself as beyond even the clutches of memory. If you say you can remember the 60s you weren’t really there, you know.

Yet for many, a decade is not merely defined by the passage of ten short years. It could be argued from both a social and cultural perspective that 1970s Britain didn’t really commence until Bowie’s first (1972) Top of the Pops appearance, and that the decade didn’t actually end until Thatcher’s second (crushing) election win in 1983. It’s an idea seemingly shared by Fonda’s character, condensing as he does the course of ten groundbreaking years into a fleeting window of little more than twelve months: ‘It was just 66 and early 67’,’ he solemnly declares, in a pensive and melancholy parting shot. ‘That’s all it was.’

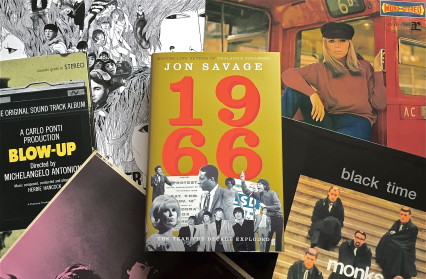

In similarly pinpointing the artistic and political eruption of 1966 – The Year The Decade Exploded – as the epicentre of the period’s creativity and conflict, author Jon Savage nevertheless makes a compelling case for a cultural reappraisal tinged with the appropriate degree of hard-nosed reflection. ‘The problem with the pop culture of the 1960s,’ he considers ‘…as exciting and innovative though it was, was that it set up expectations and desires that could never be satisfied. Teens were valued not for themselves but for the cash in their pocket.’ It is a view that was echoed at the time by the radical writers of the underground magazine International Times, possibly the first British publication to set itself apart from the prevailing ‘Swinging London’ love-in. In October of that year it proclaimed that London ‘isn’t quite as switched on as our ad-men make out’. Adding, for good measure, ‘if you decide you want to change things at base, you are taking on governments; you are deciding to be your own government. Change begins with you.’

Though the preceding twelve months had seen pop music and politics, via both Dylan and Donovan amongst others, exchange furtive looks and glancing blows it took a series of real wars played out on national television – the political tinderboxes of Saigon and Selma – to truly initiate the timeless soundtrack of (in the U.S. at least) a nation tearing itself apart, Jon Savage memorably describes the mania as ‘like the high whine of a wire twisting in the wind, a constant backdrop that frazzled thought and fostered a mood of public hysteria.’ On the other side of the Atlantic, the inequality of opportunity that continued to divide men and women at least began to experience the semblance of a tipping point away from traditional male privilege, a mindset that frequently embraced music (more often than not, black American music) and an increasingly political (often career-limiting) consciousness. The author is especially keen to call out the then radical stance of the sublime Dusty Springfield who cut short a tour of South Africa when it became apparent that she would not be permitted to perform before unsegregated audiences, as had been contractually agreed.

Deconstructing the year on a month-by-month basis Savage leads the reader on a meandering and fascinating exploration, one instinctively inspired by the evocative trappings of a corresponding 7-inch single. 1966 was the last year that singles outsold albums, an indication perhaps of the decade’s mounting solemnity, and it is via the cultural resonance of these shiny black plastic incendiary devices that the story is incrementally revealed. Savage sees these vinyl relics not as dusty historical curios but as precious vessels of social change and personal emancipation: ‘Condensed within the two-to-three-minute format, the possibilities of 1966 are expressed with an extraordinary electricity and intensity,’ the author declares. ‘They still sound explosive today, fifty years later.’

It was only a few weeks ago that I stood rifling through the racks of Bleecker Street Records in the ’66-heavy environs of New York’s Greenwich Village. Chancing upon the incongruous discovery of an ostensibly eccentric recording by SSgt Barry Sadler, ‘The Ballad of the Green Berets’, and its equally conformist B-side ‘Letter From Vietnam’, I was somewhat taken aback to learn from a store employee that this was a record that sold enough copies to reach the top of the U.S. charts and remain their for five weeks straight. Spawning a million-selling parent album of the same name, and an internecine chart war between the creative forces of left and right, it remains a cultural curiosity that perfectly represents the increasingly ruptured fault lines of American society, the widening divide between young and old, and the accelerating erosion of unquestioning patriotism:

Back at home a young wife waits

Her Green Beret has met his fate

He has died for those oppressed

Leaving her this last request

Put silver wings on my son’s chest

Make him one of America’s best

He’ll be a man they’ll test one day

Have him win the Green Beret

Jon Savage uses this record as the perfect introduction to the month of March, a de facto analysis of the societal roadblocks that were being swiftly constructed across the U.S.A. Sadler’s starch-collared deference remains an authentic expression of those that held (and still hold) the deaths of U.S. servicemen to be a worthy sacrifice, but the author’s contemporary elevation of it to a key cultural touchstone is wholly characteristic of his fascination with the elements of pop history that have been conveniently written out of the predominant cultural narrative. Within the pages of 1966, Savage hardly sidesteps the phenomenon that was The Beatles – how could he? – but his consideration exists in the analysis of what The Beatles were influenced by as much as what they actually influenced. In a similar vein, his absorbing take on the ragbag of contradictions that is the fabulous Monks – a rudimentary yet glorious garage rock band comprised of American GIs based in Germany – perfectly encapsulates the period’s eccentricities without ever evading the perpetual and often sobering battle between political reality and artistic swagger.

Ultimately, Jon Savage is to be congratulated for confounding the preconceptions of the there’s-nothing-new-you-can-tell-me-about-this brigade once again. Having achieved the same in his now seminal punk text England’s Dreaming, and surpassing it via the pages of the extraordinary and revelatory Teenage, 1966 sets a new benchmark in cultural storytelling.

Truly, it was the best of times, it was the worst of times.

Craig Austin is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.