Adam Somerset takes us on a tour of the National Museum of Wales with companion in hand.

The review of “War’s Hell” (Wales Arts Review 26th July) prompted a visit to the exhibition at the National Museum and then to the galleries surrounding. The exhibition is dominated, through size, by Christopher Williams’s “The Charge of the Welsh Division at Mametz Wood 11th July 1916.” Facilitated by Lloyd George it hung for a period in 10 Downing Street. If it is the dominant image in terms of sheer dimensions it is less so, as recognised by the Wales Arts Review critic, in artistic stature.

Peter Lord in The Tradition (Parthian 2016) sees it “as a picture unequivocal in its condemnation of the savagery of the event.” That, however, holds back from viewing it in aesthetic terms. Gary Raymond for Wales Arts Review got it right. Smaller privately conceived art cuts deep in a way that public art “for hallowed halls, billiard rooms and municipal gathering spots” does not. Raymond correctly looks to the small acute studies of Muirhead Bone to see the privation, the desperation and the loneliness of war service. The Tradition picks on Christopher Williams and Margaret Lindsay Williams for its images of the Great War. But this is to prefer literalness of depiction over depth of artistry. Art works its effect indirectly; a capacity for a high quality of mimesis is not its inner value.

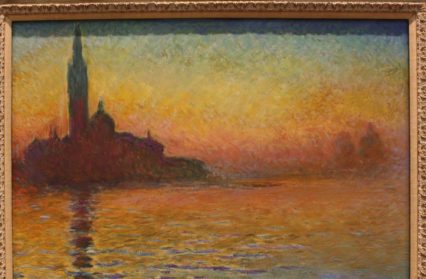

A few galleries away Monet in Venice is not literal, but his San Maggiore is glorious.

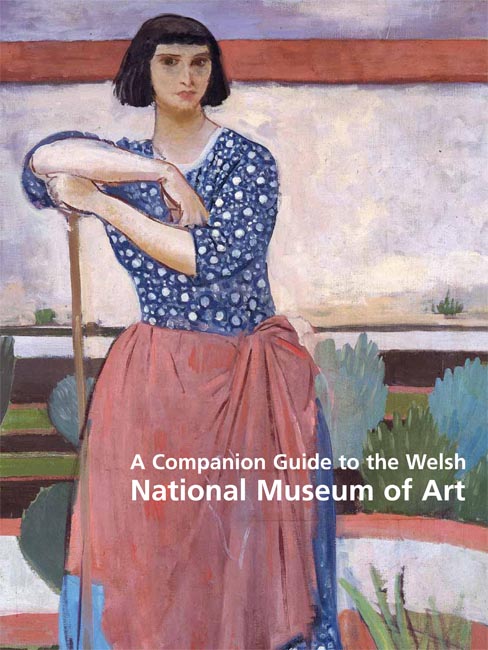

Monet in Venice does not feature in the Museum’s A Companion Guide to the Welsh National Museum of Art. The selection chooses a study of Rouen Cathedral. The text contained on a half-page beneath the image is crisp and compressed. The version of Rouen in Cardiff “Setting Sun (Symphony in Grey and Pink” is one of twenty, exhibited by Durand-Ruel in 1895 to acclaim. The thick impasto is due to the artist’s constant reworking. Gwendoline Davies purchased it in wartime, in 1917. Its cost was £1350. The Cardiff Companion is a good companion, joining historical consideration and critical evaluation in harness.

Art is more than aesthetic evaluation. Works were thought out and prepared, composed and executed, praised and damned, bought and sold. The Companion embraces one hundred and fifty examples of the works in Cardiff. Four to five paragraphs of explanatory text accompany the work of eleven authors. It is manageable in weight and scale, its language accessible and non-technical.

Art is more than aesthetic evaluation. Works were thought out and prepared, composed and executed, praised and damned, bought and sold. The Companion embraces one hundred and fifty examples of the works in Cardiff. Four to five paragraphs of explanatory text accompany the work of eleven authors. It is manageable in weight and scale, its language accessible and non-technical.

The one hundred and fifty mini-essays roam across history and aesthetics, biography and art history, quotation and matters of technique, ownership and commercial passage. Oliver Fairclough opens with six pages on the stages of formation of the institution itself. In 1882, William Menelaus, manager of the Dowlais iron and steel works, is donor of thirty-eight paintings. James Pyke Thompson, a director of the milling firm Spillers, is creator of Turner House in Penarth and owner of extensive watercolours, oils and ceramics. Chemist Robert Drane is instrumental in building the collection of ceramics, including the porcelains from Swansea and Nantgarw.

The early Keepers of the Museum are more dependent on donation than rich coffers of their own for acquisition. Goscombe John gives sculptures, prints, paintings and drawings by the hundreds. Donors are numerous although the Museum also makes its own serendipitous purchases. Gwen John’s “Girl in Blue” costs it twenty pounds. The Museum’s history moves to a double highpoint with the move to the mighty Cathays Park building and the receipt of the Davies bequest.

Fairclough concludes by lightly touching on the manifoldness of a national museum. There are tugs, not easily reconciled, in opposing directions. Cultural meanings, or sociological readings, have eased aside notions of pure aesthetic value. The canon becomes an object less for adoration than a good kicking. The very notion of a museum has changed irrevocably. Scholars have learned to co-exist with merchandisers and marketers. “In the 1990’s,” writes Fairclough with careful phrasing, “the Museum was sometimes seen to lack engagement with its audience, and to be overly focused on the art of the past.” That may have been so, but museums are now hugely, monumentally popular.

At their very least these images from the past are depictions of a piece of history. The Companion adds many an item of illuminating detail and context. The portrait of Katheryn of Berain by Adriaen van Cronenburgh is a favourite, with the subject’s fearless gaze and the hand resting on a skull. Anne Pritchard elaborates that Katheryn’s grandfather was an illegitimate son of the monarch and she herself had six children by no fewer than four husbands. An assessment of a silver gilt dish and ewer runs through the turbulent career of lawyer Sir John Trevor of Brynkinallt, Denbighshire.

Interesting items in art history itself occur. “A Calm” looks to be a masterly exercise in sea, ship and cloud. Notwithstanding appearance the artist, Jan van de Cappelle, was a self-taught amateur and incidentally scion of a family of wealth and owner of seven Rembrandt oils and over five hundred drawings. Sir Frank Brangwyn’s “A Tank in Action” and its companion are in Cardiff because Lord Iveagh did not like the result of what he had commissioned. The Museum owns a monumental canvas of Sir William Watkins-Wynn and two comrades. 1947 was not a rich time in Britain’s history but the artist Pompeo Batoni had so fallen from fashion that it was acquired for a modest £230. By contrast in 1909 Gwendoline Davies paid a good £6350 for a Corot.

Stylistic comments are few but telling. An illuminating comment is made on two portraits by the Haarlem artist Maarten van Heemskerck. The treatment of musculature suggests the artist has an acquaintance with Michelangelo. Richard Wilson in an Italian landscape uses black and white chalk together to enhance his effects of light and atmosphere. Beth McIntyre notes that Turner’s exaggerated perspective in drawing Ewenny Priory owes much to Piranesi. Ruskin is ecstatic in his comment on Turner again when he paints Flint Castle from across the water. The effect has been part-made by applying a wet sponge to the watercolour. But Turner has also created highlights by removing paint to reveal the paper’s white. The advanced tool was most likely a sharpened thumbnail.

The crisp elucidations do not permit heavy aesthetic explorations. The most popular painting of the collection is revealed by Bryony Dawkes to have changed on the way to its final version. X-ray photography applied to “La Parisienne” reveals trace of possible doorway and curtains suggesting an initial concept of conventional design. Rodin broke with all artistic convention when he made his St John spread his weight equally over both legs. Natalia Goncharova is identified as an exponent of Rayonism, or “spatial forms which are obtained by the crossing of rays from various objects.” Andrew Renton is good on two vases by Elizabeth Fritsch. He places her status among artists in ceramics and also illuminatingly points to the musical background in the making of the pattern.

Quotations are used sparely. Gwen John is touching in her happiness in small things: “what a feeling of contentment my room gives me… in the evening my room gives me a quite extraordinary feeling of pleasure.” It enhances the viewing of her 1907 “A Corner of the Artist’s Room.” Less satisfaction elsewhere; Sisley on the Gower with his paintbrush is sublime but he is not impressed by the accommodation. Of the hotel at Storr’s Rock “the beds have to be seen to be believed” and the food is either “bad” or “less bad”. Picasso is cited on a predecessor “My one and only master, Cezanne, was like the father of us all.” But Peter Prendergast’s vision of Blaenau Ffestiniog ends with a nice line from the artist. “My father was digging out coal to make profits for other people. But then coal keeps people’s houses warm. Painting keeps people’s souls warm.”

A Companion Guide to the Welsh National Museum of Art ed. Oliver Fairclough(National Museum of Wales 2011 176 pp £15.00)