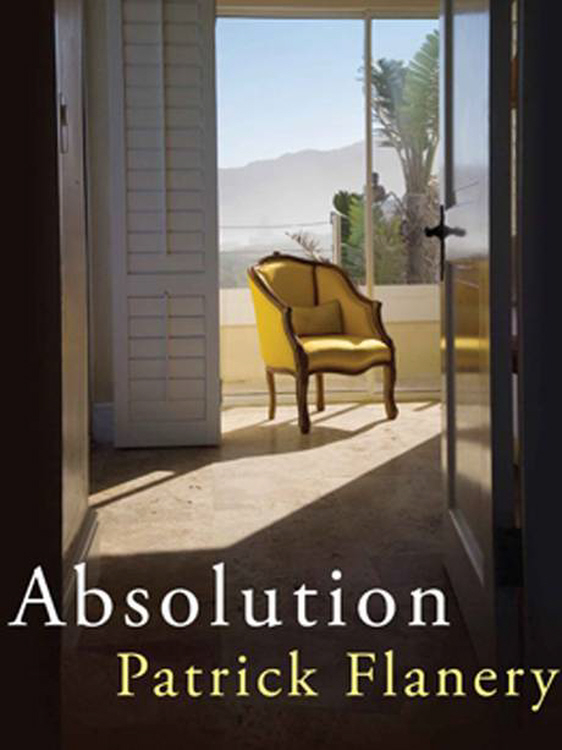

Patrick Flanery’s debut novel Absolution is an unnerving and acutely observant book. It has at its heart the issue of political terrorism, and serves as a stark hair-of-the-dog in the post-apartheid hangover of contemporary South Africa. The fairly complex story revolves around an ageing left-wing white South Aftican writer, Clare Wald, and her relationship with her biographer Sam Leroux, who provides the missing link between herself and her daughter Laura – presumed dead since her involvement with MK, the extremist branch of the ANC. The novel, which subtly evokes shades of Great Expectationsin its power dynamic, is written in what amounts to three voices: Clare’s own; Sam Leroux’s; and Clare’s attempts to inhabit the memory of Laura’s final months, pieced together from letters, diaries and her own imagination.

by Patrick Flanery

385 pages. Atlantic Books. £12.99

Absolution – I think deliberately – masquerades as a species of detective novel; or maybe crime fiction. Much of the plot centres around a life-changing episode in all the protagonists’ histories, in which each voice attempts to concretise events into a truthful account. It’s a book in which the same ground is revisited and reviewed, in the fashion of a murderer returning to the scene of a crime. Gradually though, what emerges is this: that the more memory and experience are forensically examined, the less tangible they reveal themselves to be. Some way through the novel, I understood it to be much less concerned with plot than with the fabric of the narrative itself, and so the subtle strength and unlikely poetry of its imperatives slowly realised their impact.

Patrick Flanery employs many devices through which to get his points across, not least by having his heroine Clare, an author herself, actually writing an autobiography entitled ‘Absolution’, which, by her own admission is thinly disguised as fiction. ‘It’s easier to sell a novel than a weird hybrid of essay and fiction and family and national history,’ she admits. Regrettably, this is true. And again, like a criminal unable to conceal his guilt, Flanery uses Clare as a mouthpiece to openly express his own lament.

Because really this novel is an eloquent, if ice-cold, investigation into the nature of truth, and, more specifically, the notion of trust. And in South Africa’s case, the long, slow and alarmingly permanent-seeming erosion of it. What Flanery seems to achieve in Absolution is an honest and challenging portrait of a complicated, fragile country crippled by violence and mistrust. The mood of paranoia that dominates the text is potent to the point of asphyxiation, and it’s within the pervasiveness of this apocalyptic culture of fear that Flanery questions almost everyone’s position: black, white, left, right, rich, poor, well-intentioned, maliciously-motivated. Nobody gets away uninterrogated.

So what we’re confronted with is a sort of brutally uncompromising refusal to form opinion. Instead, Flanery seems to be holding a mirror up and saying: Look; look at this mess that’s happening here. Look at how it’s happened. What he doesn’t offer are solutions.

What Flanery seems to achieve in Absolution is an honest and challenging portrait of a complicated, fragile country crippled by violence and mistrust.

Despite the sub-tropical location, the atmosphere of the novel is decidedly chilly. It’s a landscape of harsh escarpments, horrifying beach-side torture, air-con and isolating steel security shutters. Clare’s son remarks, ‘You didn’t raise us to be warm,’ which reads as something of an understatement. It’s the same blunt economy of emotion one derives from J.M. Coetzee, and it makes me consider the mindset of a people whose existential fibre is so intrinsically eclipsed by politics, from all angles, that a kind of cynical detachment takes the place of human feeling, however obliquely.

There’s fierce political passion running through the nervous system of this book and its cultural history, but what Flanery seems to be questioning is the human cost; the psychological price. Where the political agenda encroaches so completely on the arena of family and relationship, we’re faced with a nullifying of the warmth of love and connectivity. This resonates with Doris Lessing’s heavily political sections in The Golden Notebook, themselves rooted in sub-Saharan Africa, and, on a less serious, but nonetheless equally pertinent note, Nancy Mitford’s admission in The Pursuit of Love that Christian, the Communist party devotee, is a man who ‘goes through the world attached to nobody – people are nothing in his life. The women who have been in love with him have suffered bitterly because he has not even noticed that they are there.’

Although Clare and her family were historically radical whites in support of black equality, she finds herself no more integrated with the black community, and increasingly mistrustful and aware of the perpetuating divides in post-apartheid South Africa than ever. Her betrayal of and estrangement from her own family in a web of fractured political disagreement has rendered her lonely, regretful and isolated. Externally, the resentments and scars of a society she fought so hard to change seem far more entrenched than her naïve younger self could possibly have imagined, and she even finds herself buying into the enduring habits of segregation despite herself.

Flanery tackles the taboos of our modern global-capitalist world, by both sympathising with the causes of, and condemning the ravages of, terrorism. He takes on the issue of censorship, expanding the premise beyond the political into the personal, examining self-censorship and the concept of constructing or concealing truth. He asks in the novel, what is or isn’t acceptable: not only within the constructs of a society, just or unjust, but whether we apply those same measures of constraint or limitation to the self, and at what cost.

There are a lot of profound considerations in Absolution and some stunning writing in what is, on the whole, an admirably retrained style, At times the characters can seem strangely lacking in dimension and are almost entirely humourless, but I’m not sure if this too, isn’t deliberate.

Flanery achieves an aching hollowness in his book that represents a culture trying to heal from decades or centuries of conflict and oppression, where the very foundations of trust and respect have been turned on their heads. At one point he makes use of the African animal kingdom as a metaphor for society. It’s an oddly reversed presentation wherein the rich are the vulnerable herbivores being predated by the threatening poor. It’s a sinister illustration of the subjectivity of perspective, and although provocative at every turn, Flanery leaves us in no doubt as to his position on the state of the country, and indeed perhaps he sees South Africa as a sort of grotesquely illuminated didactic against the more subtle chiarascuro of the rest of the developed world.

‘She was a victim, perhaps,’ he writes of Clare after she has been the subject of a robbery, ‘but not innocent.’