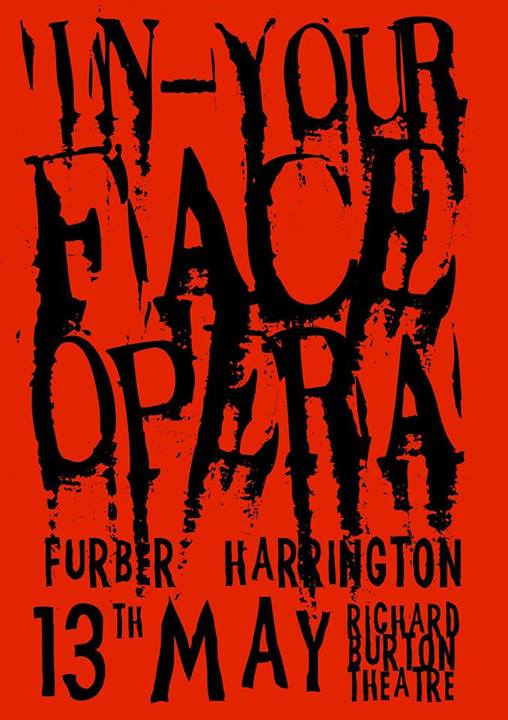

Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, Richard Burton Theatre, Dora Stoutzker Hall, May 13.

In-Your-Face Opera Double Bill:

The Pin Drops

Words and music by David Harrington

The Man, the Corpse and the Soldier

Words and Music by Lewis Furber

Singers/actors: Conal Bembridge-Sayers / David Harrington / Katrina Nimmo / Lei Roberts – presented by Marjorie’s Hat Box

Musicians of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama

Conducted by Jack Lovell

Oratorio

Bhava

Words and music by Ben Lunn, from ancient Buddhist texts.

Singers and musicians of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama

Conductor: Ben Lunn

Marjorie’s Hat Box

‘Warning: very strong language and upsetting themes’.

I confess my heart sinks whenever I’m presented with such cautions before a performance. Not because I’m easily shocked – I’m quite the reverse. But rarely do they turn out to signal genuinely disturbing, or even thought-provoking, content – and, in any case, generally speaking I don’t believe we should be warned of that in art, because it infantilises the audience. Challenging taboos and investigating dark areas of human experience are vital and serious functions of art in any culture, including through comedy.

But depressingly often, the warning merely turns out to mean a dialogue peppered with ‘fucks’ and ‘cunts’ (hardly shocking), and action containing violence and/or sex of some graphic variety designed for cosmetic impact. I’ve no objection to either per se, but if those are the sole attractions, I’m likely to become bored, as I did in David Harrington’s The Pin Drops, staged as part of Atmospheres New Music Festival: a day-long showcase of work by graduating composers from the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama. In Harrington’s story, an abused and aging opera singer – the valiant and capable Katrina Nimmo – kills and eats her offensive husband and then her lover. Interestingly, the woman-on-man violence happened largely off-stage. We can enjoy watching women being abused and humiliated, but not their men-folk it seems.

According to the blurb, this piece (and the far more thoughtful, yet hardly insipid, The Man, the Corpse and the Soldier, by Lewis Furber) were an ‘innovative hybrid form of shock and music theatre’ which aimed to ‘thrill and arouse the minds of a modern audience so bombarded by dreary formulaic blockbusters and low-brow media’. Exactly what this means I’m not sure – and I suspect (or hope) that whoever wrote it did not intend ‘low-brow’ to denote cultural inferiority. But empty narrative gestures by way of rape and physical violence leave me cold; especially when, as in Harrington’s piece, the characterisation relies on gender cliché and casual voyeurism – and Harrington can no longer plead student in mitigation. At any rate, I find that people who have lived experience of ‘upsetting themes’ rarely go on to present them as titillation for others. Musically, Harrington’s pastiche cabaret and show tunes were certainly enjoyable, and elements of his theatre were effective, even amusingly done in places – the diva’s direct addressing of the audience early on, for example. But I’d look elsewhere for truly adult themes.

…Such as – by way of illustration – Welsh National Opera’s recent staging of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut. This was a production which induced a kind of moral panic in some audience members, with its scenes of sexual slavery, scantily-clad prostitutes and twisted, mafioso thuggery (the production raised other objections too, but that’s a different debate). The point is, director Mariusz Treliński devised those scenes precisely to show a conjunction between sex, money and power, and the hypocrisy of a society – ours today, as much as Puccini’s, or Prévost’s (from whom his libretto came) – in which women like Manon are literally created by men to be fantasies or ‘luxury toys’. How far Treliński’s staging succeeded is moot – and whether his singing actors were up to the task. But his intention was far from perversity for its own sake, or to glamourise sexual violence; rather, to take an intelligent look at deep-seated social problems caused by the clash of moral values with opposing fears and desires.

Thankfully, the second opera on this Atmospheres double bill, The Man, the Corpse and the Soldier, showed real promise in that regard. Lewis Furber’s subject encompassed male rape, homophobia, racism, murder and mental disintegration – and he managed not to be glib about any of them, despite that gleeful rhetoric of the programme note. In Furber’s story, utilising the same set as Harrington’s (a room in a flat, with the instrumental ensemble part-hidden up stage), the Man strangles his male lover but tries to continue living as normal alongside the corpse, mentally unravelling until his own demise at the hands of a psychopathic soldier. Lei Roberts showed real torment, loss and self-hatred in the main role, which demanded he alone hold the audience for long stretches (too long, actually, between the initial murder and the soldier’s appearance). Furber’s stagecraft and dramatic sense will doubtless develop as he gains experience, but his basis was sound and his characters had substance. Above all, Furber’s music was both inventive and expressive of the Man’s inner twists and turns (the subtle use of electric guitar and percussion being one of many highlights). Conductor Jack Lovell navigated his impressive band with aplomb through this and Harrington’s score.

*

Sierra Goldberg

Going stylistically and thematically from chalk to cheese, the next (and final) item on the Atmospheres agenda was Ben Lunn’s Bhava, described by the composer as an ‘oratorio-like work’. Lunn’s title refers to a Buddhist concept of the continuous cycles of life, death and reincarnation, and the four sections of his piece are, appropriately enough, designed to be performable in any order ‘and still make musical and narrative sense’. The musical material is strong, and I see no reason why this flexibility shouldn’t work in practice – possibly because the piece has, in fact, no narrative in conventional linear story terms. Rather, each section is an exposition of, or reflection on, a certain Buddhist theme. But whatever the section order, the work could benefit from some judicious editing in places to mitigate a slight sense of losing one’s way within its hour-long span.

That said, this is an admirably ambitious and broadly successful work, and Lunn, who conducted the première, did well in coaxing sustained commitment from his assembled RWCMD volunteers: a chamber choir, plus nine-piece ensemble with an emphasis on resonant, deep toned and percussive sounds. The instrumental line-up, as well as Lunn’s use of vocal chant and declamation, clearly reflects his inspiration in Tibetan ritual music. There was some extremely effective writing for the bassoon and trombone in particular, with echoes of shawm and rag-dun. Cello, double bass, harp and organ also featured alongside thundering bass drum and tom toms, tam tams and ringing crotales to create an evocative and colourful sound world with some great, crashing climaxes. An added piano jarred somewhat timbrally – and sheer volume overpowered the choir in places. But the singers coped impressively with some high tessitura lines and their pitching was accurate and diction clear for the most part.

Lunn quoted further influences in his biographical note, from Bataille to Perotin and, of contemporary composers, Rădulescu, Pärt and the late Jonathan Harvey. It was this last who felt most present here – in spirit more than through direct musical allusion, but clearly so in the delicately ethereal Bhava I, for instance. This sole instrumental section was inspired by a comparison between the blossoming lily in the pond and the idea of enlightenment. Bhavas II-IV were based on Tibetan texts: respectively an excerpt from the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the ‘100 Syllable Mantra’ and ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’.

It wasn’t clear from the programme note how far the religious meaning of these texts is, in itself, important to Lunn – and perhaps that doesn’t matter. Clearly, he has been moved by them, and the larger wisdom they represent, to urge his audience to greater awareness of matters spiritual, ancient and modern. The result is a work that is as heartfelt as it is thoughtful, and which signals an interesting turn to a more tonal language for its composer. My one caution going forward would be to guard against a too-literal adoption of non-western music styles. Bhava manages to avoid that – just – with its co-inspiration in 11th century organum. But the line between celebrating another culture and appropriating it is sometimes a fine one.