Steph Power attended a concert by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales at Hoddinott Hall featuring the works of Panufnik, Britten, Matthews, Otaka and Lutoslawski.

Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, 28th March 2013

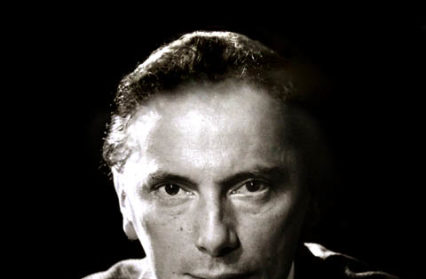

Andrzej Panufnik – Katyń Epitaph

Benjamin Britten / Colin Matthews – Double Concerto

Hisatada Otaka – Flute Concerto

Witold Lutosławski – Concerto for Orchestra

Conductor: Tadaaki Otaka

Flute: Adam Walker

Violin: Anthony Marwood

Viola: Lawrence Power

Between January and May, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales has programmed works by Benjamin Britten (1913-76) in five concerts, including tonight’s, in celebration of his birth centenary in 2013. This is evidence of the very high regard in which Britten is held; the more so given that his reputation rests upon his operas (and, to a lesser degree, other vocal works) rather than his instrumental music – and certainly not upon those minor pieces forming part of BBC NOW’s current series. If only Britten’s some-time friend Witold Lutosławski (1913-94) were appreciated in the UK to anything like the same degree relative to his own, actual compositional stature. Alas, Lutosławski’s music is by no means as familiar to UK audiences as that of the home-grown Britten and so his centenary, also falling this year, is attracting far less attention* despite his being one of the major composers of the twentieth century, whose significance is acknowledged far beyond his native Poland. Tonight’s offering from BBC NOW’s spring season cast a welcome ray of light upon Lutosławski in the form of his most popular piece by far, the Concerto for Orchestra (1950-54) – but not, sadly, upon any of the four symphonies, nor upon his mature orchestral oeuvre.

The concert opened with a piece by Lutosławski’s compatriot and another, much closer, friend (as well as formative, war-time piano duet partner), Andrzej Panufnik, who managed an extremely dangerous defection to the West in 1954, just as the ‘accessible’ Concerto for Orchestra was about to rehabilitate Lutosławski with Poland’s Soviet masters. Panufnik wrote the Katyń Epitaph (1967/69) to commemorate the massacre of fifteen thousand defenseless Polish prisoners-of-war in Katyń Forest by the Russians in 1943 and ‘to express my personal sorrow that the Western civilised nations have allowed this crime to remain forgotten’. It is a short piece (just eight minutes); simple in structure but highly intense, and so a difficult opener for the orchestra. On this occasion, the ensemble took a while to settle upon their entry following leader Lesley Hatfield’s emotionally piercing opening solo, but conductor Tadaaki Otaka quickly gathered his forces into a convincing crescendo to the close.

Perhaps the string sound in the Panufnik could have been warmer and fuller to greater effect – but there were no such issues in the following work, the Double Concerto for violin, viola and orchestra by Britten and Colin Matthews, which was beautifully played by soloists (Anthony Marwood and the outstanding Lawrence Power) and orchestra alike. For a composer aged just eighteen, as Britten was at the time of writing in 1932, pre-Opus 1, this piece is a remarkable achievement and it is fully deserving of its place in the repertoire since its posthumous premiere in 1987. However, one wonders how much of the perceived quality of the piece is down to its stunning orchestration, which was done by Colin Matthews (b1946), not Britten, who left the piece as an unfinished student work. Matthews assures us that the orchestration is ‘virtually 100% Britten’ and taken from markings that Britten himself made on his short-score. But the instrumental colours, gestures and sheer sophistication are almost eerily prescient of the mature Britten and it would hardly be surprising if Matthews had been, albeit unconsciously, influenced by his intimate knowledge of Britten’s developed style. Whether he was or not, the finished Double Concerto is a clear example of the extent to which orchestration is an art in itself; intrinsic to the compositional process and much more than a matter of obeying markings on paper.

Alas for Hisatada Otaka (1911-51, father of tonight’s conductor), his Flute Concerto (1948, revised 1951) did not benefit from its close proximity to the impressive Britten/Matthews, although it made for a gently evocative start to the second half in this nicely put together programme of three concertos and an epitaph. The combination of French-influenced light melodicism with occasional flashes of Viennese-ish waltz evinced Otaka’s European training, but the solo flute part (albeit played with unassuming warmth by Adam Walker) was full of clichéd pentatonic swoops and harmonic-minor runs just too reminiscent of composers like Jacques Ibert. There was nothing here to tax either soloist or orchestra, nor to challenge the audience. But perhaps that was the point, given that the work preceded the virtuosic rollercoaster that is Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra.

The Flute Concerto was quickly forgotten in the opening pulsating timpani of the Lutosławski, which commanded attention from the start; indeed, the respect and affection which the orchestra holds for their Conductor Laureate were palpable here in Tadaaki Otaka’s riveting performance. The playing was superb across the orchestra and throughout this bold and vital piece as he shaped each of the three movements with a combination of sure pacing and minute attention to detail, interweaving the complex, ever-changing instrumental sections and solo lines with a discreet, almost alchemical skill. Rhythmic precision, textural balance and nuanced phrasing – all were present in exemplary abundance and made as compelling a case as any for the piece’s designation as a ‘great work’ (if any were needed) in spite of Lutosławski’s own attempts to dismiss it in hindsight as ‘a work which I could not rank among the most important ones in my music … [which] originated in a way which I had not quite expected, as a sort of a result of what was my episodic symbiosis with folk music.’ Speaking later of his difficulties at that time with the socrealizm of the authorities’ Soviet-adopted artistic stance, he further dismissed the nationalism of the Concerto for Orchestra, saying ‘I wrote as I was able, since I could not yet write as I wished’. For sure, the work in no way represents Lutosławski’s mature style or later aesthetic concerns (as in, for example, his exploration of aleatoric techniques from 1960 onwards, after hearing part of a broadcast of John Cage’s Piano Concerto). But it is a fantastic piece and performances as electric as this remind one that there simply is no substitute for hearing music of exceptional calibre performed live by brilliant exponents. Would that BBC NOW audiences were to be given the chance to explore the composer’s unique rethinking of symphonic form through an Otaka/Lutosławski cycle of symphonies and other of his orchestral works.

* the highest profile celebration is the Philharmonia Orchestra’s Woven Words Festival www.woven-words.co.uk

Tom Service devoted Radio 3’s Music Matters to Lutosławski on Jan 19th: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01pyffp

Photo credit: Camilla Jessel Panufnik

You might also like…

Cath Barton attends the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama (RWCMD) for a celebration of Benjamin Britten on what would have been his 106th birthday.

Steph Power is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.