Steph Power visited the St. David’s Hall, Cardiff to witness the latest BBC NOW performance of Huw Watkins and Gustav Mahler. Conductored by Thomas Søndergård.

Thomas Søndergård has remarked on several occasions that he finds it absolutely necessary to perform contemporary music, saying for instance: ‘if I don’t do contemporary music, I feel it’s strange … to go back to Beethoven’s 5th – or even Mahler’s 5th – because I need … new colours and new ideas to go on with the standard repertoire.’ In tonight’s concert, he demonstrated just how beneficial such an ethos can be for new and established repertoire alike, by rounding off his first year as BBC National Orchestra of Wales’ Principal Conductor with terrific performances of Huw Watkins’ Violin Concerto (2010) and that very Fifth Symphony of Gustav Mahler (written in 1901-2).

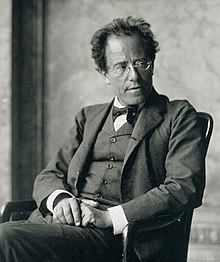

Indeed, this was the first time that Søndergård has ever conducted Mahler 5, making this concert a particularly resounding success – for the Fifth is a symphony so potentially bewildering in its innovative formal design and complex orchestration (both subsequently oft-revised) that Gustav Mahler himself once despaired of its receiving a convincing performance under any other conductor than himself; after its poor reception in Berlin and Prague in 1905 under Artur Nikisch, he wrote that ‘a musical score is a book with seven seals. Even the conductors who can decipher it present it to the public soaked in their own interpretations. For that reason there must be a tradition, and no one can create it but I.’ Alas, albeit more celebrated in his lifetime as a conductor than as a composer, Gustav Mahler died in 1911 without committing his own interpretation to phonograph or gramophone for us to hear what he may have wished to pass down by way of performing tradition – and, moreover, having eschewed tempo markings in any of his scores beyond the usual broad indications. Hence, arguments continue to rage, not just about the Fifth, but about how each of his symphonies ‘should’ be interpreted.

Part of the controversy stems from Mahler’s ambiguous status as a backward-looking late-romantic and a forward-looking modernist as we will see. Such ambiguity continues to affect the reception of many composers besides Gustav Mahler well into the 21st Century in different ways – not least the still-youthful Watkins who, as he noted in an interview for last fortnight’s Wales Arts Review, is often held to be too ‘modern’ (that is, too dissonant) by mainstream audiences on the one hand, but too ‘old-fashioned’ (that is, too redolent of post-war English music) by critics and fellow composers on the other. Notwithstanding judgements based on aesthetic taste and Weltanschauung, Watkins’ music clearly owes a debt to the Benjamin Britten he has loved since childhood. So it was fitting that his Violin Concerto was paired with Mahler for this second performance in Cardiff following its première at the Proms alongside Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5; for, as Arnold Whittall has noted, ‘a strong Mahlerian influence is evident in two of the [20th] century’s most appealing post-Romantics, Britten and Shostakovich.’ Tonight, the direct line to Watkins seemed all the more apparent for Søndergård’s thrillingly insightful approach.

Credit: Hanya Chlala

The soloist was the fearsomely capable Alina Ibragimova, for whom the Concerto was written. In her hands, the violin is at once an instrument of attacking virtuosity and molten lyricism, and Watkins has rewarded her with a substantial piece utilising both characters; equally intense and often switching from one to the other in a moment. A brilliant performance to match a brilliant part – not to mention a BBC NOW on superb form – was never really in doubt, but Ibragimova has matured and (if the Proms radio broadcast is anything to go by) played with even greater depth on this occasion, throwing phrases to and fro the tightly driven orchestra with acute musical sensitivity as well as dramatic bravura. Each of the three movements (subtly subverting a classically-based fast-slow-fast design) offered combinations of a kind of expressive fury with firmly balanced, more delicately ‘held’ textures. I have a slight compositional concern regarding the relationship of the first to the third movement, as the latter seems rather to echo a gesture already made in the former than to succeed in defying expectation for a second time, with another quietly subsiding ending. But the piece is beautifully written overall; Watkins’ ear is undoubtedly alive to instrumental possibility as well as harmonic colour, and the tripartite relationship between violin, harp and punctuating bass drum was particularly satisfying at various points throughout. I look forward to hearing his forthcoming Flute Concerto, to be premièred next February at London’s Barbican Centre – interestingly here, alongside a performance of Mahler 1.

Perhaps listening to Mahler may have encouraged Watkins’ impressive instinct for knowing what to leave out as much as knowing what to put in, so to speak, instrumentally speaking. Certainly, tonight’s glowing performance of the Fifth Symphony emphasised Mahler’s rich and subtle use of orchestral colour, which made such a profound impact on the younger composers he encouraged in the Vienna of his day; figures such as Schoenberg, Webern, Zemlinsky and Berg. But, for them as for the music philosopher Theodor W. Adorno, ‘more important than … Mahler’s style are the more hidden [innovations] of his compositional method. All contemporary compositional technique lies ready in Mahler’s work under the thin cover of the late romantic language of expression.’ The grand reference here to ‘all contemporary technique’ might in fact be largely applicable to Austro-German music but, in that context, it certainly seems fair; for Mahler effectively expanded the structural boundaries of symphonic form to modernist breaking point through vast, long-range thinking, incorporating new kinds of episodic writing and variation techniques, as much as through ‘backward-looking’, romantically intensified expression. No composer since has expanded the symphony further – at least, not in terms of sheer scale and intensity of utterance.

Not only that, but Gustav Mahler incorporated all sorts of overtly ‘popular’ – and often deliberately garish – devices in his self-expressed bid to portray the ‘whole world’ in his music and to ‘make[s] objective an untrammelled subjectivity’ as Adorno put it; all sorts of ironic and parodistic sounds – from hurdy-gurdies to cow bells, via gushing sentimentality, manic waltzes and terrifying marches – find their brash way into his music alongside beautifully embedded folk tunes, literary references, the most exquisitely subtle harmonic thinking and passages of truly searing existential joy and angst.

In terms of the accepted ‘reading’ of the Fifth Symphony as a journey from ‘dark to light’, Søndergård and the BBC NOW did a superb job tonight – not least because the conductor seemed to succeed in laying out all such devices and underlying formal subtleties as they appeared, as it were; allowing them to bubble up in service of the score’s apparently sprawling forward momentum, rather than trying to shape them in too ‘conscious’ a way. Thus, the heavy Funeral March of the first movement seemed to dovetail into the clean, almost Beethovenian parallel world of the second movement Tempest with its echoing funeral march, leading naturally to a third movement Scherzo blessed with a lightly ironic touch and so on. Part of this achievement was undoubtedly due to the excellence of the orchestra, who quite simply played their socks off – with particular praise owing to the exceptional Principal Trumpet Phillippe Schartz and obbligato Principal Horn Tim Thorpe.

But another crucial aspect was Søndergård’s wonderfully unfussy phrasing and, above all, his sense of clarity and pace – most notably in the fourth movement Adagietto, made famous by Luchino Visconti’s use of it to depict heart-rending loneliness, unrequited love and impending personal doom in his film Death in Venice. Unfortunately, the film (not to mention Mahler’s apocalyptic later symphonies) seems to have encouraged many conductors to treat the Adagietto like a dirge – but not here, thank God; rather, Søndergård’s quicker tempo and transparent string sound helped to uplift the movement to its more authentic and characteristically autobiographical purpose, as a love song without words from the ecstatic Mahler to his beloved Alma, whom he was shortly to marry – and thus the conductor made sense of the ensuing glorious optimism of the symphony’s climax in its fifth movement Rondo-Finale, in which many of the work’s monumental musical and emotional themes make a final re-appearance.

Altogether, this concert offered music-making of an extremely high calibre and proved a thought-provoking, as well as celebratory, way to end the BBC NOW season. As Mahler himself said of the Fifth Symphony, ‘a completely new style demanded a new technique’. Tonight, the confident programme and the expansive, generous way in which it was delivered seemed indicative of Søndergård’s ongoing ambition to develop and shape his own vision as a conductor, as well as the playing of this exciting orchestra with which he has already forged a deep artistic resonance. Personally, I can’t wait for the new season to begin this autumn.