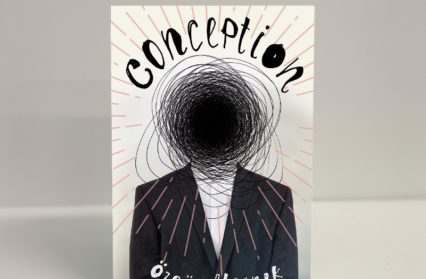

What is the meaning of conceptual art? Michelle Deininger reviews Özgür Uyanık’s new novel, Conception, which explores the nature and value of art through a sociopathic protagonist who is determined to succeed.

Conception by Özgür Uyanık follows the journeys, both literal and artistic, of the unnamed central character of the novel, who is himself a conceptual artist. Told from a first-person perspective, the reader is given in-depth and increasingly troubling access to the artist’s mind and motivations as well as detailed accounts of his travels between London (where he lives), New York and Istanbul (where he was born). The artist is spectacularly and dramatically horrible – rude to his friends, even more, unpleasant to his personal assistant, S (Samantha, shortened to S because her full name is distasteful), and a provocateur in politics, art and life in general. Petulant, self-obsessed and vain, he is perhaps one of the most distinctive and memorable sociopaths to be found in contemporary fiction. At the same time, this persona critiques and challenges settled notions of identity and provides an acerbic deconstruction of the aftermath of the empire, especially in relation to Istanbul.

Throughout the novel, there is a sustained focus on the nature and meaning of conceptual art. As the protagonist explains: ‘No one knows what it is unless it is studiously labelled and hung in the hallowed halls of a designated place of contemplative worship’ (52). In many ways, the book itself is a philosophical exploration of how the meaning of art is shaped – how it is created, curated, understood and, often, misread. The artist sees himself in the same kinds of terms, dressed in particular labels, wearing branded sunglasses, and constantly anxious about his place (and lack of sustained success) in the wider art world. Context and juxtaposition are everything. One of the especially satisfying aspects of the novel is that the protagonist’s focus on aesthetics is repeatedly echoed, even to the level of the sentence. In fact, the novel often reads like an exploration of surfaces, from the shining floors of high-end London hotels to the ‘polished concrete’ of an art exhibition in Istanbul. The conceptual art at the centre of the novel is the artist’s own piece, a work shocking in its self-destructive nature. The reader is often left wondering whether anything has any meaning or truth anymore, especially when it comes to art.

Read in conjunction with Uyanik’s recent essay, ‘My Other(ed) Self’, published in Just So you Know: Essays of Experience (Parthian, 2020), the novel takes on further resonance. From the opening pages, it is already clear that the novel is grappling with some difficult issues, including the legacy of imperialism, and the fractures caused to a sense of self by not quite fully belonging anywhere. Uyanik’s essay deals with the loss of connection with cultural heritage, in his case symbolised by shelves of unread books by well-known Turkish writers of the twentieth century. It also charts the difficulties of being a Turkish-born writer living in Wales, and the challenges posed to BAME writers through being ‘encouraged… to produce palatable cultural artefacts for a post-colonial UK marketplace’. Conception is not a ‘palatable’ novel, though there may be some irony to be found in the sheer number of references to eating, consumption and food. The unnamed artist is constantly pulled between different centres of cultural influence – the language and culture of Turkey, the consumerist attraction of Britain and the US. As the artist says to his mother ‘I never wanted to be in between… I was taken from the place of my birth and dropped into a foreign land and left to flail about… I am a rootless stranger oscillating violently between two alien realms – trying to fit into both and fitting in nowhere’ (67). That his mother’s response falls between ‘equanimity and sadism’ in its focus on the ‘glorious’ work that will undoubtedly come out of that pain speaks volumes for both their relationship and the destructive potential of art. Sadism, however, is closer to the art that the protagonist creates, and the violence that he unleashes on others.

Conception is a novel that deserves to be read slowly to fully appreciate the wordplay and sharp wit of the writing. Aside from the artist’s darkly humorous voice, a sense of undischarged violence runs through countless descriptions of people, place and culture, and the novel repeatedly draws attention to its own status as a work of art, forged in the aftermath of a post-colonial heritage. The novel’s self-aware humour comes through most clearly when the artist is in observer mode, noticing the tiny details of the world around him, though he directly rejects ‘people watching’ as an ‘abhorrent’ and ‘vacuous’ waste of time. What the reader experiences is a growing sense that these observations are being channelled through a perspective that is becoming increasingly distanced from reality. Underneath the humour are complex layers of intertwined trauma and violence while the ending, which is deeply disturbing, proves that the surfaces we see and the stories we tell ourselves often cover up ugly truths.

Conception by Özgür Uyanık is available now from Fairlight Books.

Michelle Deininger is an avid contributor at Wales Arts Review.