Nigel Jarrett reviews Stephen Walsh’s latest book, Debussy: A Painter in Sound which enriches both popular taste and serious scholarship.

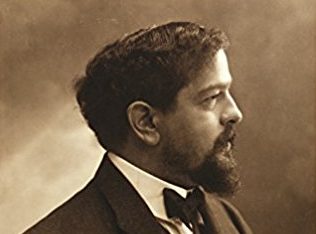

To begin at the end. In several photographs of him as an adult, the composer Claude-Achille Debussy is pictured holding a cigarette. Smoking too much, drinking too much, exercising too little, and – who knows? – a hereditary predisposition to disease all caught up with him at the age of 55, when he died of cancer. Debussy was hardly dissolute, and what we have here is as common a bunch of health issues now as it was then, and the age of the victim isn’t particularly surprising; except that in Debussy’s case it may have deprived us too early of more that would be ever-luminous in contemporary music. He was at his most ill and closest to death in the Great War, for many the historical turning-point after which, with a few exceptions, it would be impossible for composers and other artists to look back.

Stephen Walsh claims that his book is unique in dealing with music as an essential part of the biographical narrative rather than taking it as read. He means that music-lovers experience the music first; then, if they are interested, will find out about the person who wrote it. Few of these conventional biographies, the shorter ones anyway, deal adequately with the composer’s reason for being, so that there’s a frustrating disconnect: it’s easy to say music is revolutionary or reactionary but difficult to explain why without going into technicalities. Walsh regards it as natural and essential, as he has always done; among many other qualities, it’s what makes his magisterial two-volume biography of Igor Stravinsky so compelling a read and so important a contribution to musicology. (Debussy’s fabulous ballet score, Jeux, was partly eclipsed in 1913 by Stravinsky’s seismic Le Sacre du Printemps, which famously worked its audience into a lather at its première in Paris just two weeks afterwards and in the same theatre.)

A book could certainly be written about Debussy’s women, with the music, as it were, coming and going in another room. The trail through his life almost like distractions, even though his first wife, Lilly Texier, provided him with the stability of all sorts. In 1903, fresh into his fourth decade, and with several masterpieces to his name, including the recently-premiered opera Pelléas et Mélisande, he dumped her for the more cerebral Emma Bardac. Ever the evasive cad, Debussy wrote to Lily that ‘an artist is, all in all, a detestable, inward-facing man (sic) and, perhaps, a deplorable husband.’ No ‘perhaps’. Lilly attempted suicide after Debussy returned to Paris with Emma from the seaside where he described other residents there as ‘thieves for sure’. By that time, he had hit upon a method of simultaneously depicting both the literal subjects of music and one’s feelings about them (to put it crudely), as in the piano piece L’Isle joyeuse. He was also finishing his marine triptych La Mer, and further transforming solo keyboard music. Stephen Walsh corrects the popular misconception that Debussy finished, or even wrote, La Mer on a visit to an inspirational Eastbourne with Emma – he’d done that back home four months earlier; he did write piano music at the town’s Grand Hotel, and checked proofs of a piano duo version of La Mer. (The Centre du Documentation Claude Debussy believes that the orchestra proofs of La Mer were also dealt with there.) The piano music was again superb. As a teenage prodigy at the Paris Conservatoire, Debussy had nonetheless given up the possibility of piano-playing as a career in favour of composition, later influenced not so much by his musical contemporaries as by the artists and writers who interested him.

Early on, Walsh is as good as his promise not to underestimate the music: in dealing with Debussy’s student days as a part-time house pianist for two wealthy women, it’s the songs he was writing at the time that are analysed as much as the domestic arrangements involved. Biographers with less interest in the music might have researched the sexual frisson generated, certainly, in the case of Marie Vasnier, a half-decent amateur singer whose intimacy with her talented young accompanist and composer was probably, as they say, absolute. Significantly, Stephen Walsh identifies in one of the songs composed at this time (a setting of Verlaine), similarities to the love duet in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Both the influence of Wagner and the reaction against him were then central to the development of European music, especially Debussy’s. The book’s illustrations include a photograph of a twinkle-eyed Ernest Guiraud, Debussy’s composition teacher, an upholder of the status quo but a man who clearly recognised in his student’s barely-suppressible tendencies something original. Debussy’s response to the ‘languorous ecstasy’ and other ambiguities of such poetry was the beginning of his ‘impressionism’, a pejorative but unwittingly accurate term first applied to paintings at the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. Art, poetry, and music: they were all coming together, though not related in the strictly stylistic sense. Wagner’s first Bayreuth Festival was held just two years later.

Debussy’s life and musical development are tracked side by side and chronologically. Having won the almost obligatory Prix de Rome (he hated his sojourn in the Eternal City), back in Paris, and with a few prize-winners responsibilities yet to fulfil, Debussy then completed the Cinq Poèmes de Baudelaire in which his employment of the whole-tone scale (no chromatic movement of semitones) enabled him to ‘see’ music in terms of its stasis, not its inevitable onward procession. It had its provenances, not least in Russian music, Liszt, Javanese gamelan, and, to the composer’s satisfaction at least, Palestrina; but now it was central rather than peripheral or en passant. He was just twenty-seven. ‘There’s no such thing as theory,’ Debussy told Guiraud. ‘You just have to listen. Pleasure is the rule.’ The pleasure one gets from Jeux, among many examples, derives not so much from the abundance of material but from the way Debussy buries it and even the work’s structural design in a shimmer of sound, the whole, as it were, being greater than the sum of its submerged parts. When in the early 1890s more first-rate works had been written or were on the cards, such as the Proses Lyriques, the string quartet, and the opera Pelléas et Mélisande, Debussy was skint. Truth to tell, there’s not much in his extra-musical life that’s gripping or redounds to his credit. He took up with a girlfriend, Gaby Dupont, borrowed money, survived on chocolate bars and bread for lunch and in the matter of trying to settle down with another woman (it initially came to nought) was a bounder. Even if it weren’t his avowed intention, Walsh must have been glad of the opportunity to treat the opera and other major works in-depth for want of more than mundane details of his subject’s life.

Debussy’s enchanting Prelude d’après midi d’une faune, after Mallarmé, was the first orchestral piece without voices he’d written. An astonishing achievement, says Walsh, in terms of the ‘delicacy and refinement’ of its orchestration. Wagner was still present, but this is Debussy the flaneur, lingering over the music when it suited him instead of being under a compunction to head straight for a destination as per conservatoire rules. It doesn’t sound much when putting it that way but it was ground-breaking, the antecedents notwithstanding. In dealing with the three-movement Nocturnes, Walsh explains musical impressionism brilliantly, delving beneath the popular conception of a painter’s fudging of detail to discover how Debussy located what Kandinsky termed ‘interior content’. Far from being indistinct, Debussy was meticulous and calculated. How did it all work, particularly in Fêtes, the central image of Nocturnes? Walsh says, ‘Just as festivities leave a certain platonic impression on our mental retina, aside from the specifics of the event itself, so the music seems able to go directly to that retina without passing through the event, which may be attached to it afterwards as a kind of excuse or explanation.’ That’s as clear a description of how the ineffable medium of music works as one could wish for. The ‘windy-watery’ final image, Sirènes, with its vocalese for female chorus (the sirens of mythology) looked forward toJeuxand the more familial La Mer, another marine triptych.

When he married Bardac, Debussy had fifteen years to live. Piano music continued to form summits of achievement, not least the two books of Preludes and, later, the two-piano work En blanc et noir, which, Stephen Walsh avers, in its freedom of utterance ‘proclaims the mastery of the mature genius’. (He wonders whether or not the two books of Preludes were actually intended as homogeneous cycles. One pianist at least, the Serbo-American Ivan Ilić, delights in re-ordering their sequence, inspired by more than mischief.) An explosion of creative energy kept the compositions coming: the piano études, a cello sonata, a violin sonata and a sonata for flute, viola, and harp. A projected opera based on Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ – La Chute de la Maison Usher – remained fugitive; it’s been ‘completed’ a few times, most convincingly by the British musicologist Robert Orledge. Having decamped to Angers at the start of the war, Debussy returned with four works, two of them masterpieces, ‘all suggesting new avenues, new creative possibilities. Added to his worsening illness in 1915 was a maintenance row with Lilly – he’d paid no alimony for five years. Woman trouble, the war, and desperately failing health (always leading the sick down a fast-narrowing tunnel) were combining to bring him down. Flawed genius; it’s a common enough story. He died on March 25 1918, the ‘greatest French composer perhaps since Rameau.’ Debussy was the first 20th-century composer, says Stephen Walsh, who finally had to formulate the detail and design of each piece of music afresh. No-one since had done that so skilfully or with such beautiful results. He believes – and it’s ‘roughly speaking’ his own view – that Debussy is loved by many who respond instinctively to the beauty of his music without its occurring to them that he might seriously be regarded as one of the very greatest composers.

Reading the book is enhanced if there are recordings and scores to hand. It’s not much to ask; in fact, it’s a delight, but some inveterate page-turners might find it irksome. Debussy: A Painter in Sound is not only penetrating and informative but also elegantly written. It’s a combination that’s been typical of Stephen Walsh’s work from the time he began writing music criticism in London for the public prints. He now contributes to the website artsdesk.com. After the Stravinsky biography, he wrote one about Musorgsky and his circle, the kuchka. All these, including the latest, have been widely praised. It is because he deals with so-called ‘technicalities’, though not at inordinately masonic length, that his books and reviews are notches above those of writers only too glad of an opportunity to bypass them and talk about something else. That they – we – are all besotted with the music, dissected or not, goes almost without saying.

Debussy: A Painter in Sound by Stephen Walsh is available now from Faber.

Nigel Jarrett is a winner of the Rhys Davies Prize for short fiction and, in 2016, the inaugural Templar Shorts award. His latest book of stories, Who Killed Emil Kreisler? was published two years ago. Jarrett writes and reviews for, inter alia, Acumen poetry magazine, Jazz Journal, and the Wales Arts Review. For many years he was a music critic of the South Wales Argus.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.