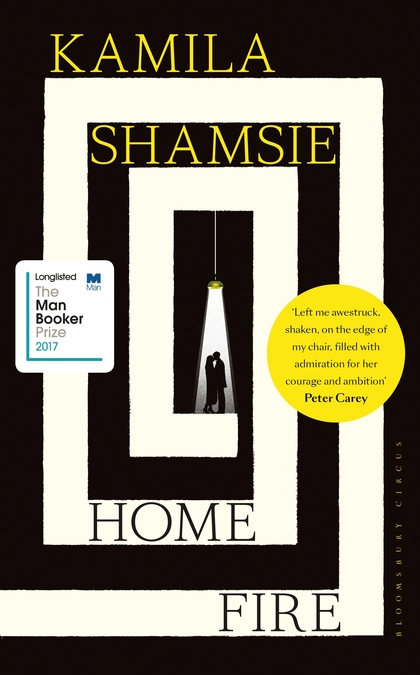

Harper Dafforn delves into the seventh novel by the award-winning writer Kamila Shamsie, Home Fire is available from Bloomsbury.

At times of political and civil unrest, tension, sedition, or oppression, classical revivals become an ascendant artistic medium for communicating hope and discontent. 2017, in Britain and America, has been a prolific year for such revivals: a few days ago I walked into Waterstones to see amongst the new arrivals in hardcover fiction Colm Toíbín’s House of Names, a novelisation of the Oresteia, and no fewer than three retellings of the Sophocles’ Three Theban Plays – none, however, have been more direct than Kamila Shamsie’s latest novel. Shamsie has soared far beyond the fashionable straits of couching an ancient tragedy in the form of a modern novel – Home Fire, longlisted for the 2017 Man Booker Prize, courageously uses the story of Antigone as a vantage from whence to bore far below the surface of complications pervading the heart of modern British society, and to create an emphasised effect of shock as much as tragic predictability. It is a contemporary tragedy which revises the meaning of fate, and our understanding of how it is created.

The novel comprises five parts, each from the perspective of one of the five principal characters, all members of two British Muslim families, the Lones and the Pashas, whose values, and patriarchs, diametrically oppose one another. The story of their increasing entwinement creeps and then hurtles towards a tragic clash of the personal and political, of human nature and the justice system.

The novel comprises five parts, each from the perspective of one of the five principal characters, all members of two British Muslim families, the Lones and the Pashas, whose values, and patriarchs, diametrically oppose one another. The story of their increasing entwinement creeps and then hurtles towards a tragic clash of the personal and political, of human nature and the justice system.

In her acknowledgements, Kamila Shamsie thanks a friend for encouraging her to “adapt Antigone in a contemporary context”, with “apologies for having done so in the form of a novel rather than a play” – though that Home Fire would lend itself beautifully to the stage or screen is tangible whilst reading the novel, it is perhaps because of its novel form that Shamsie may rank alongside Jean Anouilh in having written one of the most important adaptations of the Antigone myth since Sophocles. In the latter parts of the novel, Kamila Shamsie employs a chorus of salacious tabloids and social media, whose vitriol towards the Pasha family, methods of survey, bastardisation of “foreign” names, and political capriciousness, produce a snapshot eerily close to verisimilitude of the tyranny of the modern media – thus the chorus of citizens is restored to full potency in its ability to alternately galvanise and obstruct secular Muslim and Home Secretary Karamat Lone’s political success – lest we forget that beyond the superficiality of reportage, there are personal lives at the heart of current affairs, personal lives with which the media lack intimacy. Subtle allusions to Sophocles’ original enhance sections of prose in scenery and metaphor – compare Karamat, sitting alone, “[taking] hold of the almost-emptied glass on the chrome island” as family, guests, opponents, and advisers arrive in his kitchen to influence his judgement, with Kreon, as addressed by his son: “What a wonderful king you’d make of a desert island – you, and you alone.” (Fagles Transation, 1982) Antigone, Ismene, Haemon, Polyneices, Kreon and Tiresias, become Aneeka, Isma, Aemonn, Parvaíz, Karamat and Terri, respectively.

Furthermore, Home Fire’s polyphony derives not only from where the author has reinterpreted the concrete features of Antigone, but also from where she has elaborated on its ambiguities and points of contention. There is but one line in the play in which Antigone expresses love for Haemon, a line which is sometimes attributed to Ismene – from this, Kamila Shamsie imagines Isma as an unassuming and steadfast character with dwindling maternal authority, whose artless love for Eamonn is overshadowed by the powerful sexuality of the younger sister she has raised. Aneeka’s designs on Eamonn, and motives for achieving “justice” for her brother, contain strong nuances of this speech, apocryphal for its inconsistencies in style and characterisation:

Never, I tell you,

if I had been the mother of children

or if my husband died, exposed and rotting –

I’d never have taken this ordeal upon myself,

never defied our people’s will. What law,

you ask, do I satisfy with what I say?

A husband dead, there might have been another.

A child by another too, if I had lost the first.

But mother and father both lost in the halls of Death,

no brother could ever spring to light again.

– Translated by Robert Fagles

Here, Antigone, who previously has unwaveringly insisted that she was motivated by divine justice, launches a highly personal second justification of her acts which is apiston (ubelievable) because it is diametrically opposed to the first; in Home Fire, however, the divine dimension is removed, and human nature – or, the unwritten laws of familial ties – forms the kernel of Aneeka’s sense of justice. This sophistic debate between nomos (law) and phusis (nature) achieves crescendo in the latter pages of the novel, in a candid scene of dialogue between Karamat and Isma – herself a student of human society and affairs, a sociologist – from which Karamat’s rhetoric emerges as seeming punitive and unnatural.

Karamat, however, is not subject to as primitive a form of hubris as his template, Kreon; his urges for Muslims to renounce certain religious practises are hubristic – and hypocritical for somebody who still recites Ayat-al Kursi “as a kind of reflex” – but “well-intentioned”, from within the context of an Islamophobic society. His solution to prevent Muslims from being labelled as terrorists is to misguidedly encourage them not to behave like Muslims: “Don’t set yourselves apart in the way you dress, the way you think, the way you look, the outdated codes of behaviour you cling to, the ideologies to which you attach your loyalties. Because if you do, you will be treated differently – not because of racism, though that does still exist, but because you insist on your difference from everyone else[.]” With the apogee of the media’s hysteria in the final part of the book comes the disturbing knowledge that Muslims all over the country are offered this as the authoritative solution as their community indubitably comes under fire. The consequences for Karamat, who has tried to divorce himself from the past, are – as they were for Kreon – even more ruinous.

The middle-section of the novel, recounting Parvaíz’s radicalisation, is harrowing; the orphaned, manqué nineteen-year-old – whose career prospects, according to his sister, are slim – is groomed by an ISIS recruiter more aware than he is of his father’s jihadist legacy. Farooq exploits the absence of a masculine role model in his life and perverts his sense of what it is to ‘be a man’, before persuading Parvaíz, to fly to Raqqa and stranding him in the Caliphate. Two young men are killed trying to quit the consequences that have defined them – the moulds set by paternal expectations.

A knowledge of Sophocles is not required: the physicality of the ending would defy the expectations of a classical scholar, where the fates of the remaining characters are not imploded but forecast to implode. In powerful figura, Kamila Shamsie terminates the novel at an earlier point than is traditional, and the complexities of Home Fire are ongoing.

Home Fire is available now from Bloomsbury

Kamila Shamsie