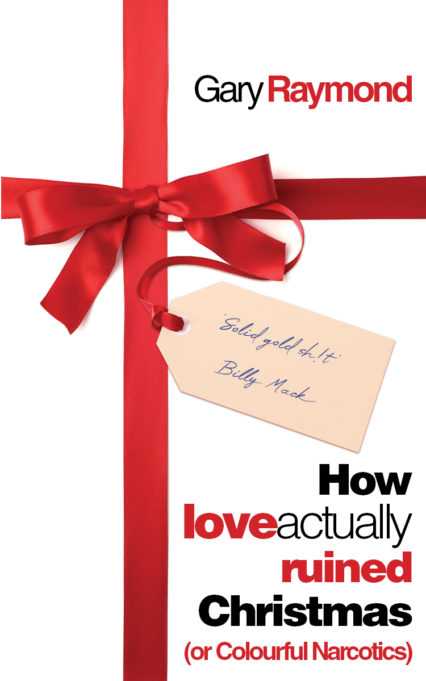

Gary Raymond‘s latest book How Love Actually Ruined Christmas, written during the lockdown, is a caustic, hilarious scene-by-scene response to Love Actually, a film the hatred for which he has been unable to shake off. Here, Wales Arts Review brings you the foreword from the book, written by film historian Dr Lisa Smithstead, as she reflects on her own relationship with one of the most popular British Christmas movies of all time.

I remember quite clearly the first time I saw Love Actually because some trauma is hard to repress. I was an undergraduate film student at the time. As such, I was possessed of obnoxiously strong opinions about Good Film and was perhaps not the ideal target audience. As the lights went down at the University cinema, I distinctly recall a growing feeling of realisation that everyone else around me was having a very different experience. When the credits finally rolled and I turned to see friends with happy tears in their eyes declaring it to be ‘so lovely’, I wondered if I’d somehow drifted into a parallel universe. Had everyone else been watching a different movie?

Several drinks and perplexing exchanges later (‘…but it’s just so sad’, ‘…but it’s just so charming,’ ‘…but wow, what a cast!’), I was willing to concede that perhaps there was in fact something wrong with me.

Thanks to the existence of this book, 20-year old me finally feel validated.

If Christmas is – according to Worst Best Friend Ever Andrew Lincoln – a time when we ‘tell the truth’, How Love Actually Ruined Christmas follows through on this promise with aplomb. Gary Raymond’s analysis is the anti-love letter to all things Richard Curtis: a scene-by-scene takedown of every paper-thin plot point, every excruciating piece of dialogue and every half-arsed characterisation.

Drawing on his considerable expertise as a critic, author and film fanatic, Raymond pulls apart what’s actually wrong with Love Actually – from plot holes to production design and the pernicious ideology underpinning much of its lazy narrative. Raymond offers new insight into the fundamentals that the film gets wrong (what the hell is going on with the timelines in each character segment? Why exactly is it fun for everyone to loudly proclaim that Martine McCutcheon’s character is, like, really fat – ha ha ha?). He also presents a fresh analysis of those scenes we think we know inside out (Alan Rickman’s character, for example, might not be quite as much of a bastard as we first thought…).

When I was asked to write this foreword, I was apprehensive. Largely because it involved having to re-watch the movie. I’ve resisted doing so for years. Instead, I’ve taken miserly joy as a Film Studies lecturer in handing out copies of Lindy West’s wonderful Jezebel article ‘I Rewatched Love Actually and Am Here to Ruin it For You’ to crestfallen undergraduates in the final week of Winter term.

As a feminist film historian and as a human woman, Love Actually has always bothered me. Because it’s a movie in which – as many commentators have since pointed out – women are essentially voiceless. They lack any genuine agency, set up as the prizes and possessions of a network of deeply unlikeable male characters. The film follows this premise to its ultimate end by positing its most ‘romantic’ storyline as the one in which the object of male affection is rendered wholly mute by a language barrier. Grotesquely sexist behaviour is never called out by any of the female characters who instead cue the audience to laugh at each joke made at their expense. Add to that its overwhelming whiteness and wealth and there’s not a great deal left to like, even if Hugh Grant does do a silly dance.

When I finally settled down to re-watch it with my newborn son (apologising as I did so for inflicting this experience upon him), my initial reaction was horror at the realisation this film is over two hours long. This horror then mutated in interesting ways as the layers of Problematic that I’d never fully clocked the first-time round snowballed with the introduction of each new character. What stands out more than anything peering back into the murky waters of the early 2000s is its relentless misogyny. This turns out to be inseparable from its fatphobia, occasional casual transphobia, and the cringe-inducing notion that to be British is to use ‘piss’, ‘shit’ and ‘fuck’ to punctuate one’s sentences – and my gosh isn’t that all just charming.

I’m also guilty, though, of resisting a total dismissal of the film’s merits by appealing to that one redeeming feature. That familiar plea of ‘I accept it’s not a good film, but I do love the bit when…’ My father-in-law, on a behind-the-scenes visit to No. 10 a few years ago, gleefully did that dance down those stairs. That’s a lot of people’s ‘moment’. For others, it’s the flashcards. Others still have a soft spot for the precocious kid, who Raymond rightly pegs as a potential future incel. My own personal push back is ‘…but Emma Thompson.’ You know, just generally: Emma Thompson. It can’t be that bad if it has Emma Thompson in it, even if it amounts to about 10 minutes of total screen time. This take has been swiftly remedied, however, by reading Raymond’s clear explanation here of why her character is possibly the original Karen in a film that clearly hates women.

The more I watched it, the more my love-hate obsessions with it grew, and the more this book seemed a necessary intervention to tackle that broad consensus that Love Actually is not just good, but a ‘classic’ of the rom-com genre. How Love Actually Ruined Christmas isn’t simply an exercise in trashing something everyone loves, however. It’s far too easy to take the contrary stance, to be That Guy for the sake of it. For all its wit, Raymond’s takedown is at heart a sincere intervention, highlighting the insidious aspects of the film. His analysis pinpoints a nastiness inherent within the bulk of its characterisations and humour fuelled by classist and sexist stereotypes that register significantly differently with hindsight.

If interrogating all that doesn’t sound entirely appealing, fear not. Gary Raymond’s scene-by-scene deconstruction pulls apart the worst the film has to offer with considerable humour, always witty in his clap backs to each offensive notion the film presents as humorously endearing. If you are equally perplexed by the popularity of this film – if you just can’t understand how this random assemblage of unappealing, barely fleshed out characters even constitutes a movie – then this book is for you. If, on the other hand, you have a soft spot for it, at the very least enjoy a fresh take on things. See if we can’t persuade you that, actually, as Raymond suggests, ‘cynicism has its uses’.

How Love Actually Ruined Christmas (or Colourful Narcotics) by Gary Raymond is available now from Parthian Books.

Gary Raymond is an editor and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.