Michelle Deininger reviews the politically-driven novel, Ironopolis by Glen James Brown, which is set in a semi-fictionalised Middlesbrough.

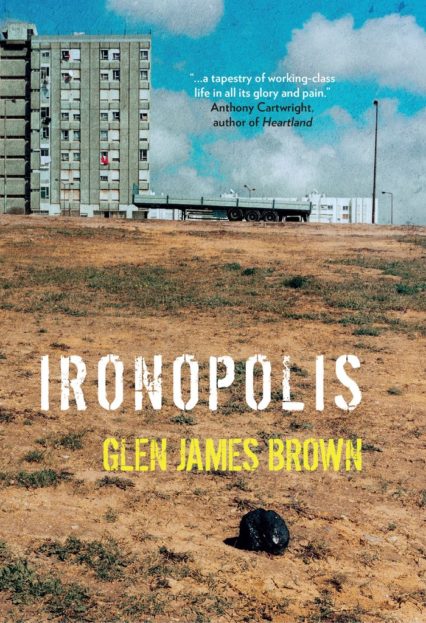

With its cover depicting a tower block, window sills strewed with wet washing, and a lump of something in the foreground that might be a rock, or could equally be dried excrement, Ironopolis could be described as a novel that illuminates working-class communities in every ugly detail.

Glen James Brown’s novel is set in a semi-fictionalised Middlesbrough, a city that was heavily bombed in the Second World War because of its huge iron and steel industries. The Burn Estate, known locally and with bleak humour as Ironopolis, is built on top of the Victorian terraces that served the growing industrial workforce of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Ironopolis envisions the slow dilapidation and death of the estate, a social housing experiment in brutalist architecture that imprisons not just the bodies but the minds of the people who live there. It traces the experiences of the residents who will be displaced by the so-called ‘regeneration’ proposed by the manipulative and exploitative housing association, Rowan Tree, who plan to raze the community to the ground once again and rebuild with higher rents and less secure tenancies. Under these layers of brick, concrete and steel lies a network of nineteenth-century sewers, tunnels and wells which are integral to the estate’s sense of identity, history and mythology. It is this intricacy and painstaking attention to the interconnection that lifts the novel beyond its portrayal of the ugliness of certain aspects of working-class realities to something beautiful.

This dark and crumbling subterranean network mirrors the lives of the characters who live above the surface and are striving for connection, intimacy and meaning in a world of alienation. All are damaged in some way by mental, emotional or physical trauma, which is often exacerbated by their brutal surroundings. The novel is comprised of a series of self-contained sections, often narrated by one character and telling the stories of others.

Jean Barr, whose overly intimate letters to an art dealer, Stephan, open the novel, is married to the violent sociopath Vincent, the unofficial kingpin of the estate. Her letters detail the slow degeneration of her physical health through breast cancer. Jean’s son, Alan, is different, other, and a target for the estate’s bullies who trick him into falling into the well. Similarly, Jim, a Frankenstein fan, is left emotionally and physically broken after a fall down the same well, shunned by the community because of his physical disabilities and tarred with accusations of child abuse and abduction because of his grotesque appearance. Gambling addict Corina, Jim’s sister, has a hair salon that slowly loses all its customers as the residents are moved from their homes. The loss of customers echoes the gradual erosion of her relationship with her daughter, irreparably damaged by Corina’s gambling. These are just a handful of the people that inhabit Brown’s world of the Burn Estate – all with stories to tell, all with pasts that are fundamentally connected.

The novel keeps returning to the elusive Una Cruickshank, daughter of a misfit mother, who leaves the Burn Estate to become an artist. Her paintings continually reconnect the place she grew up in and the characters who still live there. Jean’s letters to Stephan reconstruct tantalising scraps of Una’s past that are never fully realised or completely explained. Una, then, as her name evoking singularity suggests, remains an enigma throughout while her paintings obsessively imagine riverbank scenes and the figure of Peg Powler, a mythical entity of grotesque beauty, who haunts the sewers of the Burn Estate and terrifies generations of children.

Readers may well make parallels with Stephen King’s sewer-dwelling clown, Pennywise, from the chilling 1980s novel It, but Peg Powler is no derivative, originating in Teeside urban legend with roots dating back centuries. She haunts children’s nightmares and lures men to their deaths in the murky waters of the well. The figure of Peg Powler reads as a symbol, in many ways, of a pervasive sense of powerlessness, of being trapped – characters are drawn to her, siren-like, as they are to drugs, drink, and needless violence in a quest for meaning.

Brown walks a careful line between ugliness and beauty in the novel, contrasting the camaraderie and community of the rave scene of the 90s, for instance, with the brutal realities of territorial rivalry in an estate designed to satisfy the tastes of the architect, not the needs of the people. There is an authenticity to the portrayal of powerlessness in the face of mass corporations and the systematic failure of successive governments to ensure these communities flourish. There are many moments of hope, sometimes in the simple act of telling a story, or of being heard. But there are also journeys of discovery. Jim, for example, finds a sense of belonging and a way of being that fulfils him when he falls in love with fellow raver Adam. Annabelle, a young mother and Corina’s estranged daughter, is accepted to study at an art school in Brighton, inspired by the work of Una that she snuck off to see as a teenager in Stephan’s art gallery in London.

Glen James Brown’s Ironopolis is a complex, polyphonic novel that plays with voice, truth, and authenticity as well as being highly experimental in its use of typography, structuring and layering. For example, in the fifth section, ‘Uxo’, the narrative voice of Alan Barr is almost overwhelmed by his incessant use of footnotes, transcriptions of conversations and excerpts from journals. Yet what Brown suggests, through this innovative palimpsest technique, is that there is no single story of this working-class community. Every single thread is interconnected, through family, geography, history and, often, conflict. Threads are key, and it is no coincidence that Una Cruickshank lives in Loom Street or that Alan Barr talks of the ‘labyrinth’ of his family’s history. Corina’s mother knits the ‘Terrible Thing’, a shapeless, monstrous mass that creeps across the carpet, and represents the slow unravelling of her mind in every dropped stitch. The Burn Estate is the minotaur’s lair, and the interconnections are the threads that enable characters to escape and survive or, as is often the case, condemn them to batterings, humiliations or death.

Brown incorporates elements of myth, urban legend, history and intertextuality to create a work that is highly disturbing, brutal in its ugliness, and yet also hauntingly beautiful. To find this level of structural and technical brilliance in a debut novel is rare. To find one that speaks to working-class experience with empathy and, at times, aching authenticity is rarer still. This is an author to watch.

Glen James Brown’s Ironopolis is out now with Parthian Books.

More work by Michelle Deininger on Wales Arts Review is available to read.