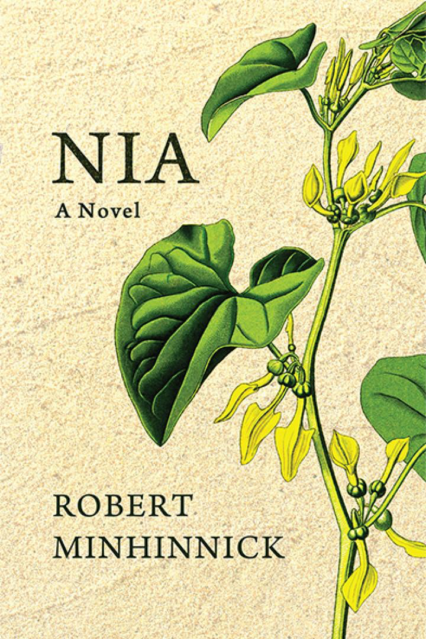

Gareth Kent reviews Robert Minhinnick’s ode to storytelling in his immersive new novel Nia, where dreams mesh with reality.

This isn’t a story…

No?

This is a memory.

Are they different?

In Nia, dreams mesh with reality, and stories coalesce into a narrative that may sometimes leave the reader reeling from a sense of vertigo. While Nia is the third novel in Robert Minhinnick’s Sea Holly series, each novel can be read in isolation – as is the case with this review. The series concerns the lives of the Vine family and those around them in a fictitious Welsh coastal town inspired by Porthcawl – The Caib. The titular protagonist, Nia Vine, is a single mother on the cusp of achieving her dream of exploring an unmapped cave system known as the Shwyl. Joining her on this journey are two childhood friends – Skye and Ike – whose professional lives allows them to enjoy the perks of frequent travel – a fact which contributes to Nia’s mounting sense of inadequacy.

Nia’s dreams and memories infringe upon the narrative during this trip into the unmapped bowels of the Shwyl cave system and provide some clues regarding her circumstances. Despite her adventurous spirit it soon becomes apparent that Nia occasionally views her being a parent as a constraint limiting her ability to explore, a fact which is juxtaposed to the guilt she feels for leaving Ffrez – her daughter – during this three-day expedition. We also learn of Nia’s chief desire to be a good mother, to avoid repeating the same mistakes of her parents, and the immediately overt suggestion of traumatic repression. As such, the novel is rife with metaphoric imagery – a friendly-looking dog from a distance becomes a fox bearing bloodied teeth; flowers in the shape of the birth canal are buried in the dunes; a goat is described as ‘god’s sacrificial throat’, yet is also regarded a sphinx.

Nia’s dreams and memories infringe upon the narrative during this trip into the unmapped bowels of the Shwyl cave system and provide some clues regarding her circumstances. Despite her adventurous spirit it soon becomes apparent that Nia occasionally views her being a parent as a constraint limiting her ability to explore, a fact which is juxtaposed to the guilt she feels for leaving Ffrez – her daughter – during this three-day expedition. We also learn of Nia’s chief desire to be a good mother, to avoid repeating the same mistakes of her parents, and the immediately overt suggestion of traumatic repression. As such, the novel is rife with metaphoric imagery – a friendly-looking dog from a distance becomes a fox bearing bloodied teeth; flowers in the shape of the birth canal are buried in the dunes; a goat is described as ‘god’s sacrificial throat’, yet is also regarded a sphinx.

There is also a strong environmentalist undercurrent to the novel, and as Minhinnick is a founder of Friends of the Earth Cymru and Sustainable Wales, this comes as little surprise. The decline of the town – where its residents are pushed to the outskirts to make way for holidayers – is likened to the destruction of its natural environment. Indeed, the realisation that human pollution extends well beyond our reach is made clear within the Shwyl where costa cups, ‘pesticides and slurry’, manage to seep into even the most desolate of places:

If she had a chance to look Nia knew there’d be grains of plastic and Styrofoam under her knees. All that plastic washed up on uninhabited islands. Pitcairn, wasn’t it? More than remote.

When it comes to style, the novel’s prose veers on the lyrical. Speech is always unmarked, and this is a device that frequently causes the voices of its characters to blend into a chaotic concoction characteristic of poetic prose. Everything blends together, dream infringes upon reality and reality upon dreams. The result is a powerful deliberation on memory and storytelling. Nia provides an examination of narratorial reliability. The novel considers how history, memories, and dreams often get muddled, and how the truth, while submerged, can surface in unpredictable ways. Ultimately, the novel has a metafictional function that forwards the notion that everything – particularly memory – is subject to a retelling. This subjugation is either through a disjuncture between memory and reality through dreams, traumatic repression, or time’s precipitation. The novel’s concern with storytelling and memory is made clear in one section when, while deep in the caves, our intrepid explorers gather around a campfire to tell each other stories that may or may not be entirely fictional:

It was another of his stories, because what was Ike but one of the dreamers who haunted this place, their tales made real by the telling, the same dreams that went round with the carousels.

Through the memory’s subjugation to its retelling, details get lost in time or mixed with other memories, stories, and dreams. The result is a recognition that notions of reliability fail to hold, and memory is exposed as a fallible and evanescent lens. Memories are revealed as a collection of disjointed shards that make up the mosaic of an individual’s life. The assimilation of dreams and lived experiences are that which result in the stories we tell. By highlighting this unreliability, however, the novel provides credence to the validity of storytelling as a means of grappling with traumatic experiences via metaphoric devices and imagery. Indeed, Nia figures storytelling as an alternative means of giving voice to that which we cannot address directly.

While its lack of exposition means Nia can often feel like a tough reading experience, the confusion it incites is simultaneously one of its core strengths. By not guiding readers too eagerly the novel places us with ease into the mind of its capricious protagonist, and the result is a dizzying, yet, brilliant carrousel of delirium.

Nia by Robert Minhinnick is available now from Seren.

You might also like…

Rabeea Saleem reviews Bad Dreams by Tessa Hadley, showing how her stories capture the multifaceted life experiences of so many women.

Gareth Kent is a contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.