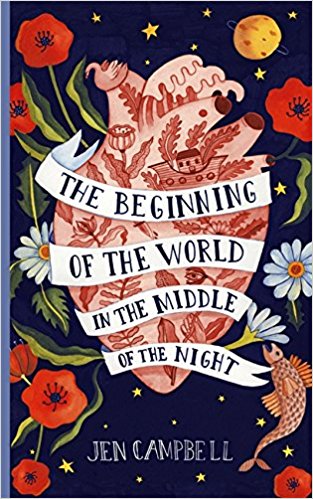

Carolyn Percy casts a critical eye over a new collection of short stories by Jen Campbell, in her review of The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night.

Hearts for sale: red, live, raw, bloody and beating; Ghosts, bottled in jars and sold; an island hotel where you can be closer to your deceased loved one, and a girl who supposedly has one foot in the world of the living and the other in the land of the dead; children who are part plant and a ‘mermaid’ on display in a local aquarium.

These are just some of the weird and wonderful things you’ll encounter between the covers of The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night, the debut short story collection from award winning poet and Sunday Times best-selling author Jen Campbell, whose previous work includes non-fiction (Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops, More Weird Things Customers Say in Bookshops and The Bookshop Book), poetry (The Hungry Ghost Festival) and children’s literature (Franklin’s Flying Bookshop with illustrator Katie Harnett).

The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night starts off strong with ‘Animals’, a visceral, sinister and yet strangely beguiling look at how an emotion is turned into a commodity. In a society where love and happiness are measured and indexed, hearts – be they animal, human or glass – are products for sale. The narrator has just purchased a swan heart for captive lover Cora, who has had a succession of different animal hearts, each causing a different problem:

The fox heart her nocturnal.

The deer heart made her flee.

The bear heart made her possessive.

The wolf heart gave her rage.

The narrator hopes the bird heart will tame her. Throughout, there are many of references to classic tales and myth, including the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan and the fairy tale often known as ‘The Six Swans’, as the narrator frequently muses on Swan motifs throughout history and folklore.

Jen Campbell admits she’s always been “fascinated by storytelling, and particularly fairy tales. How humans have always tried to explain things that they can’t possibly understand with, sometimes outrageous, stories.” Indeed, she has dedicated several videos on her YouTube channel (Jen Campbell is part of the YouTube community known as ‘booktube’) to the histories of various fairy tales, including ‘Beauty & the Beast’ and ‘The Little Mermaid.’ So it’s not surprising that the opening epigraph of The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night is a quote from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: “It is true, we shall be monsters, cut off from all the world; but on that account we shall be more attached to one another.” This is reflected in both subject matter and style; her stories often explore characters, situations and settings caught in that strange area between the known and the unfamiliar, between the normal and the ‘monstrous’; her style is conversational, often going off on digressional thematic tangents before returning to the main thread, which works well in the longer stories – particularly in the title story, which is set out like a play script, and therefore mimics the seemingly random currents of and flow of spoken conversation – but doesn’t always work quite as well in some of the shorter ones, leaving them feeling as if they could’ve been expanded upon. Leaving you wanting more, however, is a better position for a story to be in than overstaying it’s welcome, and even the shortest story in the collection brims with atmosphere.

Jen Campbell admits she’s always been “fascinated by storytelling, and particularly fairy tales. How humans have always tried to explain things that they can’t possibly understand with, sometimes outrageous, stories.” Indeed, she has dedicated several videos on her YouTube channel (Jen Campbell is part of the YouTube community known as ‘booktube’) to the histories of various fairy tales, including ‘Beauty & the Beast’ and ‘The Little Mermaid.’ So it’s not surprising that the opening epigraph of The Beginning of the World in the Middle of the Night is a quote from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: “It is true, we shall be monsters, cut off from all the world; but on that account we shall be more attached to one another.” This is reflected in both subject matter and style; her stories often explore characters, situations and settings caught in that strange area between the known and the unfamiliar, between the normal and the ‘monstrous’; her style is conversational, often going off on digressional thematic tangents before returning to the main thread, which works well in the longer stories – particularly in the title story, which is set out like a play script, and therefore mimics the seemingly random currents of and flow of spoken conversation – but doesn’t always work quite as well in some of the shorter ones, leaving them feeling as if they could’ve been expanded upon. Leaving you wanting more, however, is a better position for a story to be in than overstaying it’s welcome, and even the shortest story in the collection brims with atmosphere.

One more element of Jen Campbell’s writing I must point out is her representation of diversity: not only do her stories frequently feature people of different skin colours and sexual orientations and people with disabilities (Campbell lives with ECC syndrome, a genetic developmental disorder characterised by, among other things, a malformation of the hands known as ectrodactyly, and is a passionately vocal advocate for better presentation of people with disabilities in the media, arts and entertainment) but they are wonderfully portrayed – i.e. as normal. There’s no excessive attention drawn or point hammered home, these things are just presented as part of the rich background tapestry of life. The narrator in ‘Little Deaths’, for instance, makes a casual reference to her wheelchair halfway through the story, without having previously given the reader any clues that this was the case, because being disabled is merely a thing about her not what defines her.

Comparisons could be made to Angela Carter, but Jen Campbell’s stories have a quality completely their own; haunting in their imagery and powerful in their brevity.