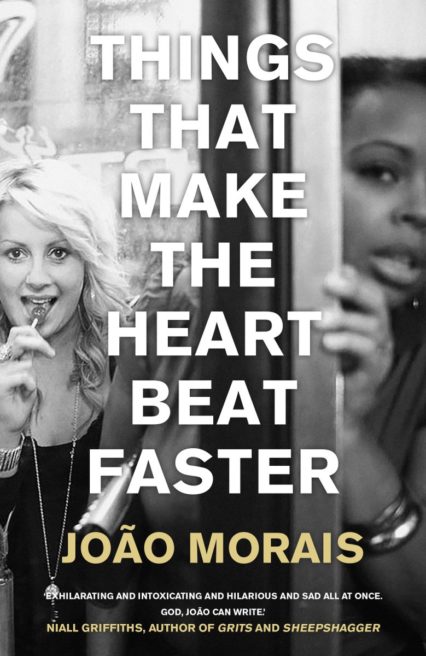

Bethan James reviews the entertaining debut collection of short stories by João Morais called Things That Make the Heart Beat Faster.

To read João Morais’s debut collection of short stories, Things That Make the Heart Beat Faster, feels a little bit like taking a very slow, indulgent stroll down a terraced street, to peer through lamp-lit windows at unknowing inhabitants. Each story, rarely exceeding ten pages, is a brief glimpse into another person’s world, as Morais captures the multifarious characters and experiences of Cardiff life in a way that is often felt but rarely articulated.

The stories in João Morais’ collection vary between first and third-person narratives, and part of the joy of finishing one story and starting another is the unexpectedness of whom we might next encounter. In first-person, Morais’s writing is at its most visceral, the characters up close, looking us squarely in the eyes. This presentness is underlined by Morais’s frequent use of colloquial Cardiff verb conjugation: I go, I feel, I want. In other, more standard pieces of prose, Morais might drop a ‘cos’ or a ‘fuck’, as if to remind the reader that these are not stories to be read at arm’s length. This familiarity ensures that we meet the characters on their own terms, which is especially important given the range of class, age and race of characters portrayed. Morais realises all characters with conviction and acuity and I was particularly impressed by his ability to capture the delicate balance of fear, disdain and boredom that two young women, Lucia and Jade, feel towards ‘slimy’ men’s advances in The Nice Guy.

Form masterfully mirrors content in the titular story, Things That Make the Heart Beat Faster, as we trip between the voices of five characters at a drug-fuelled, illegal rave. The reader is given several accounts of the same night’s events from different perspectives, as the voices mesh and blur, while in the first story of the collection, The Pavement Poet, the narrator, Jolyon, exposes the duality of living in a world in which what one thinks is rarely the same as what one says. The gulf between ‘I’m thinking/ I’m saying’ echoes through the story like a refrain until the incongruity of the thoughts and words unravel around him and he feels ‘for the first time … how alone [he is]’. Despite the character’s unpleasantness, I could not help but cringe for him as I saw the precariously balanced facades he had constructed quiver and then collapse, and could not help but pity him at the end of the story, for his embarrassment is perhaps only a little more deserved than the humiliation all of us have felt at some point or another. Morais is good at this, good at writing characters who aren’t necessarily likeable but nonetheless hold our attention on the page – characters who are, essentially, real.

Later in Morais’ collection, in the story Asking a Shadow to Dance, we meet Jordan, smoking weed in an alleyway and reluctant to return home to his mother. But like in all his stories, Morais writes with depth and nuance about the character and his situation so that we realise this behaviour is not simply teenage carelessness but something closer to directionless grief. In The Anatomy of a Beating, Morais gives voice to a belligerent bodybuilder and drug dealer, who asserts that ‘in life, violence solves everything.’ In this story especially, we see Morais’s ability to delineate a character’s psyche without ever becoming expository, so that by the end of the story when the nameless narrator learns that ‘violence doesn’t solve everything’, there is no self-righteous feeling of didacticism – it is convincingly the character’s voice.

The story Yes Kung Fu is the highlight of the collection for how it so perfectly balances humour and poignancy. It is the story of Tommo, who is attempting to see his daughter a final time before turning himself into the police, becoming entangled with Kung Fu as he causes havoc, carrying out his apparently divine mission of destroying every grey object in his path with karate chops and flying kicks. The dialogue between Tommo and Kung Fu is spectacular, especially during the car journey in which Tommo attempts to reassure Kung-Fu that ‘If you dial 666 the phone won’t be answered by Mephistopheles.’ Morais writes with wit and alacrity that always feel natural. A large part of this derives from how well crafted the characters are; Morais seems to understand that people are at their funniest when they least realise it when they are simply getting on with their daily lives. However, the humour of the stories is teased out by the author’s turn of phrase; a prison visitor who ardently kisses her convicted love interest during visiting hours is ‘like a garnet trying to retch some fish guts into his mouth’. Descriptions like this demonstrate that Morais has mastered writing and its prerequisite, observation.

In Things That Make the Heart Beat Faster, João Morais has created an accomplished, poignant and entertaining debut collection. These stories allow us to return and discover anew the realities of life in Wales’s capital city while reminding us that there is a story waiting patiently to unfurl behind every unassuming window, if only we remember to look.

Things that Make the Heart Beat Faster is available now.

Other work that Bethan James has contributed to Wales Arts Review is available to read.