Norena Shopland explores the newly reprinted edition of Mary Gordon’s Chase of the Wild Goose, a part-novel and part-biography of the Ladies of Llangollen.

Mary Gordon (1861−1941) is someone who deserves a biography. She was a doctor, prison inspector (she was the first British female prison inspector in 1908) prison reformer, suffragette and author who wrote extensively on improving women’s lives. Today she is most known for two works, Penal Discipline (1922), advocating penal reform, and the novel Chase of the Wild Goose (1936) both written after she retired aged sixty.

Chase of the Wild Goose, part-novel, part-biography of the Ladies of Llangollen was republished as The Llangollen Ladies in 1999 and Sarah Waters’ review notes:

“Gordon’s spirited, romantic account of the lives of the Ladies of Llangollen is a fascinating piece of queer literary history in its own right. A claiming of kinship, across time, with two remarkable women, it’s a deeply feminist work, a celebration of courage and nonconformity. It’s also endearingly odd! Part biography, part novel, part spiritual memoir, it’s wholly bold and eccentric and I’m delighted to see it reprinted.”

That edition has fallen out of publication and so Lurid Editions has brought out a new version in order to maintain awareness of what is an important work. Not least because it was the first time the Ladies biography had been covered and therefore claims an important place in women’s history, but also because it is one of those early books in the UK that covered same-sex relationships, albeit in muted tones.

The Ladies of Llangollen were Lady Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755–1831), who did not, as so many biographical pieces still perpetrate, run away to avoid forced marriages. They ran away because they wanted to be together and became a cause célèbre precisely because it was so unusual for two women to want to spurn societal demands of marriage. It did attract comments that they were Sapphists (women attracted to women) and the whispers followed them throughout their lives.

The Ladies became minor celebrities in the late eighteenth/early nineteenth centuries and were visited and corresponded with many leading names of the day in the arts, literature and politics mainly because their lives were presented as the perfect friendship, the rejection of sex, requirement to work (being from gentry families they were fairly affluent) and the general aspects of life that grinds people down. They were living the ideal life of walking, reading, charitable work and rounds of visits to local people, they were everyone’s ideal life. This was a carefully constructed image to avoid the scandal of Sapphism, yet it is precisely because of this carefully constructed image that their story has survived and debated on for decades as to whether they were, or were not, people we might today recognise as lesbian.

In order to perpetrate this image, it was necessary to construct a narrative of carefully selected words and phrases fed into texts about their lives. Gordon follows this pattern but pushes the boundaries with overt hints about their love for each other. From page one, Gordon sets out this obscured narrative:

“they made a noise in the world which has never since died out, and which we, their spiritual descendants, continue to echo. It is true that they never foresaw that the hum they occasioned would join itself to the rumblings of the later volcano which cast up ourselves, suffice it that they made in their own day an exclusive and distinguished noise.”

This opening paragraph offers much to be dissected, who are “we”? Feminists? Lesbians? Both? This carefully constructed paragraph conforms to the feminist literature of the day but also to the subtle, reading-between-the-lines narrative we have come to recognise in the hidden language of queer readings.

Throughout the book Gordon leaves us hints, on the second page she writes of the ‘real reason’ for leaving Ireland and refers to “how history or scandal is made.” and refers to “the main feature of the Ladies’ lives, their great and abiding love for one another.” Throughout the book she stresses their love.

Gordon was writing at a time when LGBTQ+ literature was creeping into the public consciousness. The sexologists had opened the doors, those men and occasional women who had begun to study the nature of sexuality and had made popular words like homosexual and lesbian. They questioned the notion that same-sex attraction was an addiction to a certain act but rather were people complete in themselves, or as the French philosopher Michel Foucault put it, the homosexual had become a species. We can see the links between these early works where Chase can be placed. Radclyffe Hall had written The Well of Loneliness in 1928 and is lauded as the first openly lesbian themed novel. The sexologist Havelock Ellis, who used the word “inverted” which he argued was simply a difference not a defect, wrote the foreword to Hall’s novel (it was removed from later editions). In the early twentieth century sexology morphed into psychology with people like Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, believing people were born bisexual. Carl Jung, who founded analytical psychology, believed that some people were born homosexual and Gordon studied with him in Switzerland. She became friendly with Jung’s wife, Emma, a noted analyst in her own right and who wrote of the hostility women have to suffer from men, and it is to Emma that Gordon dedicated Chase.

Like Carl Jung, Gordon had a great interest in spiritualism and mediums and this is reflected in the final part of Chase when Gordon meets the ghosts of the Ladies, a chapter often described as slightly “odd”. In this chapter she recaps recent gains in women’s suffrage and hints “no one thinks it remarkable now if two friends prefer to live together. They do so all over the country. You two friends would be no exception nowadays” and she makes them into pioneers:

“Had you any idea how many women have been on a pilgrimage to this little old house of yours? Silently, saying nothing to anybody – but they came … you made the way straight for the time that we inherited … you dreamed us into existence.”

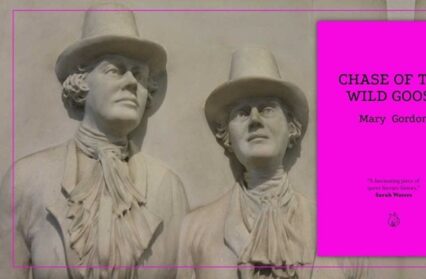

A year after the book was published Gordon used the profits to install a marble relief at St Collen’s Church, Llangollen where the Ladies are buried alongside their servant and friend Mary Caryll, “Mary the bruiser”. It is reputedly modelled, not on the Ladies of whom few images exist, but on Gordon and her partner Ada Violet ‘Vi’ Labouchere an English sculptor. The faces on the relief do bear a resemblance and Gordon seems to feel there was a connection – when she meets the ghostly Ladies she writes that Eleanor “started” when she saw her, surprised “at my likeness to her friend”, so perhaps she felt justified in modelling herself on Sarah.

Chase of the Wild Goose has an important place in LGBTQ+ literature as well as the history of sexology so it is timely that this unique book has been brought back to life by Lurid Editions.

Chase of the Wild Goose is available now from Lurid Editions.

Norena Shopland is the author of Forbidden Lives: LGBT stories from Wales; co-author of Queering Glamorgan a free research guide published by Glamorgan Archives; A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA Historical Records; A History of Women in Men’s Clothes: From Cross-Dressing to Empowerment; The Welsh Gold King.