Max Ashworth takes a look at the 1999 film, Human Traffic which featured Jip and friends exploring the excitement of the Welsh clubbing scene. He analyses how well it’s aged after 21 years.

“The weekend has landed. All that exists now is clubs, drugs, pubs and parties. I’ve got 48 hours off from the world, man. I’m gonna blow steam out my head like a screaming kettle. I’m gonna talk cod shit to strangers all night. I’m gonna lose the plot on the dance floor. The free radicals inside me are freakin’, man. Tonight I’m Jip Travolta. I’m Peter Popper. I’m going to Never-Never Land with my chosen family, man. We’re gonna get more spaced out than Neil Armstrong ever did. Anything could happen tonight, you know? This could be the best night of my life. I’ve got 73 quid in my back-burner – I’m gonna wax the lot, man. The MILKY BARS ARE ON ME! Yeah!”

Quite. So, we lurch into an opening credits sequence of juxtaposed images in delirious technicolour depicting ravers, and then black and white clips showing police failing to use restraint against protestors, accompanied by Fat Boy Slim’s ‘Build It Up Tear It Down’ which might to some eyes imply a sober tone, which does not occur. Given that it’s never part of the story or themes that follow in Human Traffic, it’s an odd collection of socio-political scenes, suggesting some serious social commentary to follow, which it does, but not in that way.

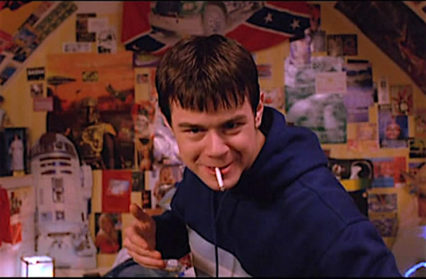

First, we are introduced to the five-strong ensemble cast, starting with Jip (John Simm), suffering from a “momentous case of Mr Floppy,” plagued by performance anxiety and being stuck in a 9-5 retail job and feeling corporately raped; he concludes his opening-credits-scene episode with, “Well, that’s me, I’m afraid.” Jip will serve as our narrator and, “If you think I’m fucked up, you should meet my friends”: Koop, a sound guy, dodgy hip-hop peddler and insanely jealous that his girlfriend, Nina, is fucking other men – it does his “nut in.” This brings us nicely to Nina, who feels like a “character out of EastEnders – the comedown version” – stuck in a 9-5 fast food shop and having a “sublife crisis” since she “fucked up” her uni interview for a degree in philosophy, and now feels rudderless.

Next Lulu. Lulu is coping well with being recently single. Yes. She really is OK with it, really. Really, she’s fine with it. “Peachy fucking creamy.” Despite this, her recent string of bad boyfriends has left her very suspicious of men. Last but not least is Moff, a role Danny Dyer was born to play, and who steals all the scenes he’s in (joking in an interview that he would have topped himself if he didn’t get the part). “Religious about not working”, a hyperactive diamond cockney geezer, happier off his ‘pickle’ and dancing all night than bother with “the hassle of the dating game”, and (talking to camera) he continues, “but with music, I can go allllll night, you know. You know what I mean? Yeah, cushti.” He points to the camera, “I knew you wouldn’t let me down. I KNEW it.”

Covering a period of 48 hours, a lot of negative reviews at the time seemed to deliberately miss the point and complain about lack of character development and plot. There is little human drama or tragedy, and no sense that anyone has learned anything, only the understandable anxieties as Monday, and reality, gets closer, and then for another five days. This is not a coming-of-age comedy like Dazed and Confused, which also happens over a restricted period of time. Nor is it Ulysses.

Nor is it Trainspotting, Drugstore Cowboy or Requiem for a Dream with their heavy-handed messages that Drugs Are Bad and Addiction Is Bad – no, duh – some may find Justin Kerrigan’s 1999 cult film irresponsible in its frank depiction of casual drug use, weekend rock stars and hedonism without repercussion, other than the hellish comedowns, of course.

And without pride or shame, I have been reliably informed that the amount of drugs consumed in Human Traffic is far from excessive, or even remotely dangerous. This said, there were a few tabloid stories which at the time were waging war against ecstasy, and there were many lurid headline obituaries on Slow News Days; maybe reckless, due to its ultimately positive message (Prof David Nutt lost his government advisory position when he provided stats to show that more people die from horse riding accidents in a year than from taking ecstasy). But this isn’t a pro-drugs film either. More a pro-take-drugs-in-moderation-because-you-think-it’s-fun film. No one embarrasses themselves, shits the bed, throws up or pulls a whitey, there’s no coked-up aggression, no violence, just 48 hours of pure escapism, man. Safe as fuck.

In fact, the only moment of tension comes when Jip poses as a rock journalist to blag his way into The Asylum, a club owned by a schizophrenic cokehead, and calls his gran, whom he pretends is his Mixmag secretary: “Has Danny Rampling confirmed his set?” “Danny who, love?” and becomes increasingly surrounded by goons. He eventually gains entrance, adopts a Delboy voice, “He who dares, my son. He who dares.” And the only moment of suspense comes when we see Moff masturbating the following morning because E gives him “the horn,” intercut with his mum climbing the stairs to his bedroom with his breakfast, and inevitably opening his door.

Nina explains to Lulu why she’s bringing her 17-year-old brother along to the club to pop his E cherry: “He’s gonna do it eventually,” Nina says, “So it might as well be with me, in case he gets in with the wrong crowd.” This is not advocating or encouraging drug use, it’s saying if you will take drugs then be smart, stick around your mates, know when you’ve had enough. Safe as fuck. Moff tells Nina’s brother, “You fucking stick with me – I’ll look after ya’. You’ll never buzz like you ever buzzed with me.” And in the final act, the aftermath, Koop reassures Moff who, in classic comedown style, apparently, is “off the drugs,” says, “When the comedown outweighs the good times, you know the party’s over, man.” Lulu adds, “It’s not like we’ll be doing this forever . . . we’ll get bored of it eventually.”

In a scene satirising over-serious documentary, a ‘Jeremy Factsman’ walks and talks us through drug distribution in clubs, referring to ‘homies’ ‘pukkas’ and ‘coin’, ending with “What’s your name? What have you had? Reach for the lasers. Safe as fuck,” before joining in and raving it up like everyone else. Nina and Lulu bump into a crew filming a documentary on British club culture and proceed to elaborately wind them up. Interviewer: “So why did you come here tonight?” Lulu says to Nina, “Can I answer that? To get ab-so-lute-ly traaashed.” “Do you take ecstasy?” “No, we used to but now we jack up on heroin . . . we never used to but then we saw Trainspotting and it made us want to do it . . . we just seem to be so impressionable . . . Hi mom!”

The first we see of Lulu, she is fellating a Coke bottle with ease, and when Moff discusses murdering Peter Andre, “It would be impolite not to torture him first,” and “like a cream puff that doesn’t touch the sides,” Moff going to extremes, “Yeah, wire coat hanger down the japs eye, really hurt the geezer,” we see the emptiness in pop-culture; what they say is not enough. When Jip says, “this could be the best night of my life,” we entertain a certain sadness under the surface, the next weekend could also be the best night of his life, or maybe the last weekend?

Of course, you don’t just learn about the character through backstory or flashback, and even though we get a glimpse – Jip’s mother works as a prostitute, dad in prison for fraud, and Koop’s deceased mother and mentally delusional father, and Moff’s hideously middle-class homelife (unfortunately Nina and Lulu are divested of similar character time), it’s just a glimpse into boring reality. Human Traffic is confident enough to reveal character without flashbacks but through dialogue and reaction – while on E the dramatis personae find it impossible to be dishonest: “dirty” and “filthy,” as some of the bad reviews accurately report.

What follows is a fourth-wall-breaking pseudo-documentary, heavily laden with pop culture references. You don’t need to know all of them, and if you get none, you’ll have been invited into their group vocabulary anyway: “Have you got your party head-on?” “Me, I’m Worzel fucking Gummage,” but you’ll recognise most of it. It doesn’t date; the episodic nature of the edit gives Human Traffic a frenetic feel especially during the segues featuring dance music and evening street montages, but the camera lingers over most of the group scenes, the conversation so organic and single-take that you expect in some scenes the actors found the material or situation too amusing to continue and the director has to regrettably employ a cutaway.

There is a wonderful reality in the dialogue, and the observations are well played. The director said that Human Traffic is a kind of facsimile of him and his clubbing friends around the mid-nineties, and I am also here to tell you that I have spent hours dancing into a sweat at some dingy club and then found myself chatting profound bollocks to my new best friend in someone else’s kitchen the following morning. The kitchen conversation between Moff and some random he’s befriended, both easily finding all sorts of tenuous similarities between Star Wars and intergalactic drug dealing, and getting equally excited by their banal observations and cod philosophy; Yoda and a bong, very funny, you had to be there.

Although released in 1999, as said the film actually depicts early to mid-nineties clubbing. Hence it is refreshingly bereft of what the millennials grew up with and take for granted, and to them, Human Traffic may appear dated and may miss the cultural zeitgeisty references. Otherwise find it ‘vintage’. Pre-mobile phone and the internet, we are spared the contrivance of text messages or emails appearing on the screen, or the story being advanced merely by someone answering their mobile phone, or by someone not answering their phone. Admittedly, there is an early scene where the phone is crucial in organising Lulu a ticket to The Big Night Out, but it serves to enhance their group vocabulary, the inventiveness and spontaneity of it, and the easy bond that these close friends have with each other, and something happily missed by internet vocabulary.

The Jip/Koop double-act communicate as if from a playbook of ritualistic statements and catchphrases. In one scene Koop somehow dives through the window into Jip’s impressively antique car, and at first, Jip appears irate, “Who the fuck do you think you are, you twat? Why don’t you use the fucking door like everyone else?!” Koop replies, “Because I’m not everybody else, fool.” Of course, one gets the feeling that Koop is being disrespectful on purpose: “Hey, don’t let me prove my masculinity to you.” “Masculinity, what? Testosterone is flowing, bruv.” “I smells a glassin’ in the air, boys,” says Jip in a broad Welsh accent. And then follows more what feels like a routine between the two, an elaborate verbal handshake, both faking anger before embracing and doing a little dance.

I don’t think you need to have been part of that scene to ‘get’ Human Traffic (but of course it helps). Canvassing a group of friends, it turns out people don’t want to talk about Human Traffic anymore, or re-live The Halcyon Days before graduation, before kids, jobs and mortgages and responsibilities happened.

They are the human traffic – for five days a week they are living in the passive tense, driving down pre-existing roads, on established routes at established speeds, following rules and signals, directions, obeying; and then trapped on a ring road, lost, stuck in a seemingly predestined phantom gridlock, delayed at Paddington, a rail replacement bus hit in the rear while stationary. Yeah. Safe as fuck.

There are three acts: the first introduces the group of friends as they get ready to go out; the second is the drug-fuelled partying at The Asylum and the after-party; the last act in the aftermath, the dreaded comedown.

On Sunday Lulu is having a rather grand luncheon with her aunt and uncle. It is a very prim and proper occasion and Lulu proves to be very good at putting another hat on. To provide the reality underneath the stilted conversation, subtitles run alongside the stiff and formal dialogue. But, Auntie proves to be adroit at picking up signals, cutting through the bollocks, and asks, “You didn’t have too much to drink last night?” Lulu, “We didn’t touch a drop.” The subtitles read ‘2 pills and ½ gram of coke’. Auntie asks, “And how is Jip?” Lulu smiles coyly and looks down, “Jip’s very well, thank you.” The subtitles read, ‘He’s a great shag’. Auntie smiles and nods wisely. The subtitles read, ‘I’m sure he is, my dear.’

Nina and Lulu celebrate Nina’s recent unemployment, after the sexual harassment from her ‘subhuman’ manager, Martin, with “semen oozing from every pore,” as he almost literally slithers over her: “are you looking after my meat, Nina?” Nina throws off her cap, “Fuck this.” We cut to a press conference at an awards ceremony, cameras flashing: “Thank you, thank you,” Nina says, “Already great to join the two million. Looking forward to sitting on my arse, reverse sleep patterns, and some hardcore Richard and Judy.”

Pre-club drinks in the pub, Jip reminds us of his anxieties, and rewrites the national anthem into “Something I can relate to.” And so we get a toe-curling moment when he stands up and starts singing his updated lyrics, and with the small ball bouncing out the karaoke syllables in the lyrics beneath until gradually, and inevitably, the whole pub has joined in, and just as you’re starting to think that this is a bit of a duff moment, the song ends and with Jip telling us, “Yeah, well, maybe not.” It’s a confident film that deliberately drops the ball and then says yeah, so what, I did it on purpose, and you know what? I might do it again. Pull my finger.

Exposing the duality of their existence, and how drugs, in this case, ecstasy, make the characters speak more freely, apparently, as you peel away at surface and superficiality as, through the characters, you see ‘reality’ anew. While high on drugs, they take life for granted, the moment belongs to them individually and as a group. But Human Traffic is always about what’s happening underneath, about what’s really happening, man. Koop interrupting the verbal sparring with Jip on the telephone by banging it on the table is a good example of cut-with-the-shit, man. Howard “Mr Nice” Marks has a cameo to discuss, or preach, from a pulpit ‘Spliff Politics’ and show how people inveigle their way into a conversation with the person who’s just skinned up, hopefully changing direction of the spliff in their favour. We cut between Marks’ ‘sermon’ and the narration it provides: due to an interloper, Felix is now in danger of not getting the spliff next and tries to bring the conversation back to him so the spliff passes his way, but wait, now the interloper has the roller engaged, they have a mutual friend, so Felix interjects ineffectually once more, “Yeah, proper homegrown,” it’s getting tight but then, shock horror, the roller’s girlfriend turns up and, “gimme some of that.” Double usurp. For a slice of life film about nothing in particular, it is surprisingly rewatchable, and quotable, 21 years later, and the film rewards you for repeat viewings.

At the afterparty, we visit Jip and Koop discussing personal things, as you do on E, apparently, but it takes a few moments to realise the camera is positioned under the glass coffee table upon which Koop is using a credit card to divvy up a couple of lines of coke, and continues obsessively throughout their conversation, which focuses on Koop’s father’s mental illness. Jip says, “So your dad thinks you’re two people? Wow, that’s properly west,” and a conversation ensues on the nature of sanity; high on drugs, are they insane right now? How do you define ‘insane’? Those conversations. Ergo, the kind of conversation you wouldn’t otherwise have had. Later Jip opens up to Lulu about being “sexually paranoid” and in a fantasy sequence, Jip gives a running commentary of his most recent sexual disappointment. Hardly small talk over coffee.

There are clear stats that show millennials’ drink and drug use peaks at roughly 20 but declines sharply through the mid-twenties. I’ve looked into it, so you don’t have to. But by all means, knock yourself out. Easily beating the baby boomers, Generation X are the real druggies, topping the graphs for all sorts of controlled goodies, declining towards the late twenties, but not as sharply.

Is it too simplistic to ask if modern communication, Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, etc, whatever, has become the new hit to chase, that next new buzz of connectivity, the social network fix as friends contribute or ‘like’ your Facebook update or shared link, tell you that your dinner looks really lovely, another Twitter follower, or even random I Can Has Cheezeburgers gifs about cats, or Brexit, and WhatsApp groups that constantly respond? Real situations (Don’t I appear popular?) get interrupted by virtual conversation; that constant buzz of the mobile, and the depressingly fifth refresh of your Facebook page. Comedown. And phone zombieism. Is it clever mitigation from the 9-5? Kill three angry birds? Or gimme gimme gimme, and kill none? And if the fun stops, maybe another anonymous 3 am tweet might perk you up a bit. Enjoy hate responsibly. Has social media inadvertently curtailed that lunchtime drink, the crafty afternoon spliff break (allegedly) drinks after work on Friday?

And with streaming services, has this encouraged a new type of binging culture? Netflix and chill. I’m from Generation X that received landline calls to spontaneous parties at 2 am and grabbed my keys and, um, well, other things, whereas millennials might say, “We have to be up at 8, it’s now 2, so let’s be naughty and watch just one more episode of Breaking Bad.”

For a seemingly otiose film about weekenders living it for the moment, there is a lot to talk about and enjoy again in Human Traffic. I can’t wait for the sequel and see how, twenty years later, these characters are now steering through, and mitigating modern life. Reach for the lasers. Safe as fuck.

For the full cast list, and other information about Human Traffic, click here.

Max Ashworth is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.