Thomas Tyrrell reviews the gothic drama film The Little Stranger based on the 2009 novel of the same name by Sarah Waters.

It is a truth universally acknowledged (or so Pride and Prejudice would have it) that the ideal marriage is between an ingenious young woman and a really expensive piece of property. The Little Stranger, an adaptation of the novel by Sarah Waters, flips the script on this. It’s the 1950s, and Hundreds Hall has been crippled by death duties and the aftermath of war. No longer the bustling Pemberley it was in the roaring twenties, the place is swathed in ivy, filled with abandoned rooms and leaking like a sieve. It is inhabited only by Mrs Ayres (Charlotte Rampling), still, the imperious matriarch from an earlier age, Roderick (Will Poulter), physically and mentally broken by the war, and Caroline (Ruth Wilson), hauled home from military service and charged with keeping the house together. Where once they were attended by a full domestic staff, they now have only a single young maid.

Into this household comes Dr Faraday (Domhnall Gleeson), representative of a rising middle class. As one of the doctors whose mouths Aneurin Bevan offered to stuff with gold in the creation of the NHS, his prospects are far brighter than those of the declining aristocracy. A budding romance with Caroline seems to offer him a giddy ascent, becoming master of the household where his mother once worked as a maid. With her as his Darcy, he seems within reach of a more brilliant marriage than even Elizabeth Bennet ever attained. But Faraday’s interest in the household begins to take on the character of an obsession, and following a mysterious spate of mysterious deaths and fires, the remaining Ayres begin to believe the house is home to a supernatural force.

In tone and content, The Little Stranger could not be more different from the last screen adaptation of a Sarah Waters novel, 2016’s The Handmaiden, which transposed the plot of Fingersmith to 1930’s Korea. That film was a riot of octopuses, Japanese erotica and lesbian sex, but here starched upper lips, Brylcreem hair and woolly cardigans abound. There’s barely so much as an on-screen kiss. Even Waters’s trademark exploration of lesbianism in history is here relegated, uncharacteristically, to the subtextual. We are told Caroline had a brilliant wartime career in the Women’s Auxilary Air Force, and the only time we really see her come to life is when she meets an old WAAF friend at a dance. They Charleston energetically, while Faraday watches from the sidelines with a look of excruciating jealousy. Sadly, this friend is never seen again, and when Caroline later agrees to be married to Faraday, the relationship is predicated on a mutual misunderstanding. He thinks he’s marrying the house, while she thinks he’s offering to take her away from it. When this becomes clear, she breaks the engagement and resolves to set off for Canada on her own.

She is the most sympathetic character in The Little Stranger, but if her emotional frigidity makes it hard to warm either to her or to Faraday, the erstwhile romantic hero, that’s partly a function of the time period, with the repressive conformism of the fifties setting the scene for its overflow in the actions of the poltergeist. None of these rattling and bangings come anywhere close to threatening the film’s 12A certificate, however, and the film’s unimaginative cinematography fails to add any pizazz to the proceedings.

At times there’s a failure to properly foreshadow a later event — I am still unsure what exactly happens behind the drawing-room curtains in one of the key scenes of the first part of the movie. At other times, it’s all too obvious. We know, almost from the moment we see the house’s central stairwell, that someone will fall down it, and a nightie-clad tumbler is duly sent flying through the air in the film’s final scenes.

Hundreds Hall itself doesn’t truly have the air of a gothic mansion, more of a middle-of-the-road National Trust property with the edges scuffed up a bit. The final twist is judicious and satisfying, if not particularly surprising, but I found myself wishing that the poltergeist posed more of a threat to the film’s stifling propriety, longing for at least some of the Grand Guignol touches that enlivened Crimson Peak (2015) — or indeed The Handmaiden. That film, at least, provoked animated discussion. Was it condemning pornography, or was it, in itself, pornographic? What did it have to tell us about the similarities between British and Japanese colonialism? With The Little Stranger, it’s all too easy to imagine a general murmur of approval, a brief discussion of class, a reference to lesbianism, and then a long, cool, starched silence.

The gothic drama, The Little Stranger is available to stream through online platforms now.

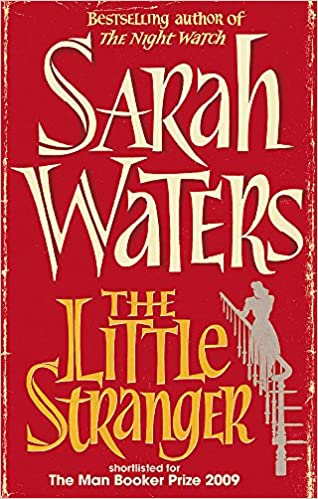

For the novel by Sarah Waters click here.

Thomas Tyrrel is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.