Phil Morris is at the Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff to review the documentary Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles by Chuck Workman.

The single word that springs to my mind when I consider the films of Orson Welles is love. Not that he ever indulged in the sentimental confection of the Hollywood romance, nor did his films express an abstracted love of humanity. Many of his leading ladies also happened to be his lovers, and his progressive political beliefs were rooted in the conviction that people were essentially good; however, the directorial eye of Welles was too acute to human vanity, pride and stupidity to make love the subject of his films. His love was for the medium of cinema itself.

Chuck Workman’s comprehensive documentary Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles presents its subject as a directorial genius with a penchant for camera trickery and visual sleight of hand. The characterisation is not unfair; Welles often moonlighted as a stage-illusionist throughout his extraordinarily diverse career, but the illusions he cast on the cinema screen were not playful essays in mere technique; they were joyous, sometimes mischievous, yet always illuminating explorations of the central theme in all great cinema – the metaphysics of looking.

The notional lost years of Welles’ career as a director – during which many of his films were butchered in post-production, tied up in complicated legal wrangles, badly marketed or uncompleted – is often attributed either to Welles’ own profligacy with money and his ‘fear of completion’, or to the corporate short-sightedness of the Hollywood studios. Such theories ignore both the revolutionary qualities of Welles’ film aesthetic, and the full comprehension studio bosses had of the dangers that it posed to their industry. Magician reveals how Welles, working initially as a maverick within the system and later as a pioneer of American independent cinema, contravened Hollywood’s business model of selling dumb escapism to the unthinking masses. He made films that drew attention to the myth-making processes of Hollywood movies, particularly their role in fostering the empty illusion of the American Dream.

Welles enjoyed complete creative control only once as a director, and that was during the making of Citizen Kane (1941), the totemic multi-perspectival deconstruction of the notion of American greatness. This control was granted due to the freakish celebrity Welles had acquired following his notorious radio adaptation of The War of the Worlds, which panicked much of the eastern seaboard of the U.S. into a state of mass hysteria with its studied imitations of news bulletins and on-the-spot live journalism. The target of that broadcast was the naïve trust millions of Americans were investing in the relatively new medium of radio. Welles’ brilliant soundscaping of the radio newsroom, his use of diegetic music and technological savvy were not deployed for the purposes of a mere hoax, it was a caution to a docile public of the dangers of mass-gullibility. Citizen Kane is similarly fashioned out of fake news reports, misreported fictions and interviews that present a narrow or over-simplified glimpse of Charles Foster Kane that never quite coalesce into an entire and coherent portrait of the man. As meta-cinema Citizen Kane remains an object of fascination for all cineastes who are aware that post-modernism did not begin with Quentin Tarantino. The film has a greater relevance for contemporary audiences in its depiction of how the news is manipulated to serve the political interests of the rich. Rupert Murdoch might lack the grandeur of Kane, but his support for the Falklands War and later invasion of Iraq has historical parallels in the manufacture of the Spanish-American War of 1898 by William Randolph Hearst, who was a model for Welles’ megalomaniacal press baron. Presently, we also have the bathetic example of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, in which a bogus reputation for straight-talking, derived from a so-called reality show, is fuelling a very sinister populism with fascist overtones.

The reputation of Welles as an artist of genius should rest less upon his technical innovations, which include ‘deep focus’ cinematography, overlapping recorded dialogue and non-linear narrative, and more on his ability to deploy the technology of a mass medium in calling attention to and then cleverly subverting its capacity to deceive. His masterpiece might have been the extraordinary The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) had RKO not marred the finally released version with some ill-judged cuts and, rather amazingly, a tacked-on and unconvincing happy ending that makes a nonsense of the preceding drama. The resulting mess begs the question as to why the studio ruined the film, taking advantage of Welles’ absence from Hollywood while he was shooting the unfinished It’s All True in Brazil. Was it just a case of mindless philistinism?

The Magnificent Ambersons charts the slow, self-destruction of a wealthy and powerful Indianapolis family from the late nineteenth century into the first decades of the twentieth. The Oscar-nominated set-designs of the film have the splendour and detail of Vincente Minelli’s later period musical Meet Me in St. Louis, but the black and white chiaroscuro photography of Stanley Cortez hints at Ambersons’ darker themes. The agent of doom for the eponymous family is not war, nor economic collapse, it is the presence of too much money in their lives. They are ruined, just like Kane, by enormous wealth and its corrupting influence on the psyche. The Ambersons’ spoiled and entitled scion George, played by Tim Holt, epitomises this moral decay, yet the more sinister antagonist turns out to be the automobile, which George describes as “a useless nuisance, which had no business being invented”. As the magnificence of the Ambersons wanes over time, the tone of the film darkens until the fall of the once great family, paralleled by the town widening out to become a darkened city, becomes a metaphor for the passing of an American age of innocence crushed under the wheels of industrial progress.

The first two films of Orson Welles exposed notions of American progress and greatness as empty shibboleths, just as the nation was emerging from the Great Depression to become a great super-power. Both films could have stood as progressive attacks on the moral vacuum at the heart of capitalism by which RKO might have accrued considerable artistic prestige. However, the demythologising of Welles’ storytelling, his repudiation of cinematic narrative orthodoxy and his challenges to audiences to understand just how they were being tricked and fooled by mainstream culture was anathema to the studio.

Welles remained very much in demand as an actor for the remainder of his life, although the films he would later direct, as in the case of The Magnificent Ambersons, would be damaged by studio heads in the editing room. Again, this should not be interpreted as wanton destruction on their part, but an attempt to curtail Welles’ playful subversions of the tropes and practices of commercial film-making. The Lady from Shanghai (1947) is a pot-boiler noir thriller that would have very little to commend it, were it not for Welles neglecting to make sense of its plot and taking the opportunity instead to deconstruct the movie-star image of his then wife Rita Hayworth. Columbia had made Hayworth a megastar with Gilda (1946) only a year before, so studio head Harry Cohn was understandably annoyed to find his most prized asset being treated in The Lady from Shanghai as the pretext for modernist noodling on the construction of the femme fatale archetype. Despite the studio cuts making the story even less comprehensible for audiences, the surreal touches of the film’s latter scenes, particularly the climactic ‘Hall of Mirrors’ sequence, are justifiably some of the most famous and most quoted in cinema.

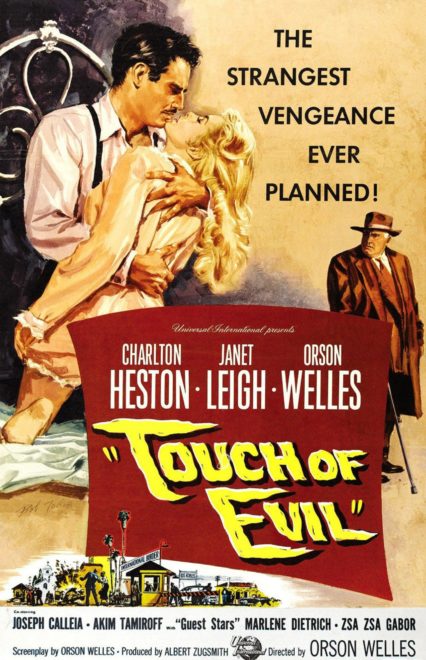

Whereas both Touch of Evil (1958) and Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) are thrillers that sensationalise and titillate audiences with the prospect of a beautiful Janet Leigh in peril at a run-down motel, it was only the latter film that remained untouched by its studio because of its efficient use of film-making technique to deliver the requisite number of screams and thrills for its audience. Touch of Evil eschews the cheap psychology of Psycho, with its sexually perverted (perhaps gay?) mummy’s boy killer, to examine the malign influence of corrupt police captain on a border-town. Norman Bates is a monster who terrifies because he is weird and unlike us; yet Welles’ antihero Hank Quinlan is, for me, far more disturbing because he is just like us, human, deeply-flawed and hateful. Touch of Evil is a much better film than Psycho as a result. Not for the first, nor last, time Welles’ film was taken from him and recut because it dared to ask deeper, more challenging and insidious questions about the human psyche than Hollywood would dare, even now.

Jean-Luc Godard once described cinema as “truth twenty-four times a second” but commercial film has always been, from the days of Georges Méliès, a repository of our idle dreams, our escapist fantasies and comforting collective delusions. The films of Orson Welles demonstrate how the processes of cinematic mythologising act as a form of mass deception. They reveal that the promise of truth that cinema appears to offer is an illusion. They show that everything we think we have seen, we might have misperceived, or at least misunderstood. His films sharpen our senses, challenge our perceptions and awaken our internal bullshit-meters. His films are a warning to us, his career is a warning to artists in an increasingly market-driven society.

The most astonishing aspect of Orson Welles’ career is that in a century during which the commercial market took on the role of artistic patron, and in a field in which the imperatives of financial success often led to cinema being described merely as an industry, one of its greatest exponents was compelled to subsidise his own creative work through acting in films much less worthy, and certainly less experimental, than his own. For the final two decades of his life, Welles used his unmistakeable, cigar-smoke-imbued vocal chords, voicing-over adverts for frozen peas and cheap sherry, to fund what sadly turned out to be glorified home-movies. While a slew of lesser talents, most notably George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, frequently paid homage to Welles at a succession of life-time achievement galas, he remained a marginal figure in Hollywood. Why did he persist then in film-making to his own financial detriment? Why not return to the stage, where his manifold talents were first recognised? The answer to these questions is one word, love. Near the end of his life Welles dryly observed, “I think I made an essential mistake in staying in movies, but it’s a mistake I can’t regret, because it’s like saying, I shouldn’t have stayed married to that woman, but I did, because I loved her.”

Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles by Chuck Workman at the Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.