Adam Somerset reviews The Square, an award-winning film directed by Ruben Östlund that casts an off-kilter light onto the art world starring Claes Bang and Dominic West.

The curators of large public galleries are a regular target for critique. Long-retired supremos of Cardiff’s public art are now known for ad hoc comments of disparagement they made to a youthful researcher by the name of Peter Lord. But the first quarter of 2018 has been exceptional, even by the standards of an enlivened art-critical scene. In the annual end-of-year summaries the Tate earned itself a Worst Exhibition of the Year accolade from The Sunday Times. That exhibition was purportedly about the Impressionists in London and wasn’t.

It has not gotten better for the Tate in 2018. The no-nonsense critic Waldemar Januszczak went to All Too Human, an apparent exhibition of British figurative art and signed off his withering article with “Tate curators, ditch the books of critical theory, enrol yourselves on a decent art-history course and get yourselves educated.”

If the Tate caused a small noise, so too has there been trouble up north in 2018. Manchester’s art-critical authorities consigned John William Waterhouse’s “Hylas and the Nymphs” to the store-room. A painting of great popularity, its removal caused a din of reproach from scholars and visitors alike. The back-tracking of lofty policy speedy.

Ruben Östlund’s much-heralded, The Square, winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, arrives at a good time. It has been reviewed as a satire on the cultural classes. It is and is done with a fine relish. Ageing donors of great age mingle with silver-tongued administrators. A new advertising generation has no truck with old media – all that matters is going viral. The competition is not other art galleries. The task is to compete with terrorism, natural disaster, populist politicians. The bedrock of good publicity is high sensation; the result that the Mad Men of 2018 come up with is both horror and comedy.

When the Museum tries to dissociate itself, that raises fresh dispute. Free speech is imperilled. The art is banal but the chattering classes get what they want, more chatter. The talk is the thing. In Manchester the wall was not left blank after John William Waterhouse’s “Hylas and the Nymphs” went down. A notice explained that the space was significant. The relationship of artist and viewing eye was secondary to linguistic exposition. “To prompt conversations about how we display and interpret artworks in Manchester’s public collection” is now the purpose.

Dominic West plays a visiting artist confounding his interviewer. His artworks in themselves are relatively minor, being pretext for a linguistic torrent of echoes and half-meanings. At Tate Britain the doughty Januszczak viewed with despair a gallery themed around identity, self and representation. Indeed, if these words were banned for a year or more, the whole edifice of art-critical exposition, not to mention Routledge’s journal empire, would collapse.

This is all good fun. In a swipe from history a gallery vacuum cleaner sucks up gravel that is part of an installation. But The Square is more than a good satire. It draws on, and blends, two traditions in film. The first is La Dolce Vita. That too won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The Square skewers the life and mores of a gilded middle class. Quite explicitly the costumes of Östlund’s willow-thin trendies are coloured black and white.

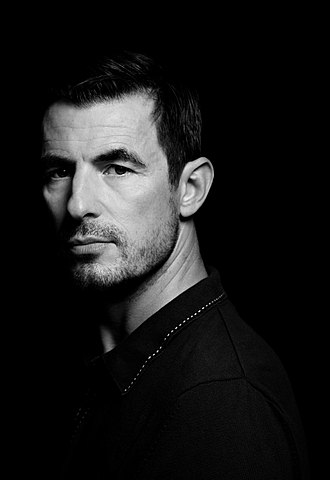

The second strand, which enhances its complexity, is the late Buñuel of the 1970’s where the secure life of the bourgeoisie is constantly under threat. This Sweden is far from the Kantian notion of the ius cosmopoliticum, the city as artefact where people may live among strangers without fear. So Claes Bang’s central character Christian is as much Candide as Mad Man. He is likeable as the disorder in his life, outside the world of art, accelerates. His clothes are impeccable, the interior of his home is perfect, his car roars at speed through the city’s underpasses, the length and grain of his stubble groomed and finely judged.

Yet all around, as in Buñuel, disorder threatens. The state art that pays his way has done away with aesthetic criteria. This new zone where art meets non-art is blurry and hazardous. The scene with Terry Notary’s performance artist Oleg is likely to join cinema’s pantheon. The scene that follows his encounter with Elisabeth Moss may not be described on a site that is open to all eyes. Even the time of post-coital rest in this world comes with a wary unspoken threat. After the disaster of Top of the Lake: China Girl Moss reveals herself here, in only a couple of scenes, as one of the best film talents of her generation.

Like Östlund’s Force Majeure from 2014, The Square does not know quite how to wrap it all up at the end. But the route there is one of wince, chuckle and continuous admiration. Östlund acid-accurate, zestful vision is wonderfully served by Fredrik Wenzel’s cinematography.

Adam Somerset is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

You might also like…

Phil Morris was at London’s Tate Modern to see a series of performance installations from Valleys Kids, a remarkable charity that has changed the lives of thousands of individuals in ex-mining communities in the South Wales Valleys.