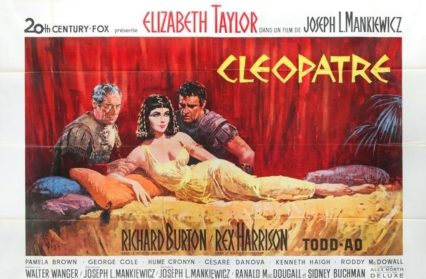

With the ‘Becoming Richard Burton’ / ‘Bywyd Richard Burton’ series due to re-open at the National Museum Wales, Wales Arts Review is publishing a series of essays to run concurrently with the exhibition, curated by Daniel G. Williams, director of the Richard Burton Centre at Swansea University. Each essay will consider a specific Burton film; here, Rob Penhallurick discusses Cleopatra (1963).

E saw Cleopatra last night with all the kids. I popped in at one point for about 10 seconds and went away and slept for another couple of hours. No reflection on the film! As a matter of fact E said this morning that the film is not at all bad — marvellous spectacle and all that.

This is Richard Burton writing in his diary on Sunday 15 August 1971. The location is just off Capri on board the 60-year-old yacht Kalizma, which he and Elizabeth Taylor had bought in 1967. The following afternoon they sailed north-west to the island of Ischia, ‘where we parked off-shore from the Isabella Regina [Hotel] where we used to live in sin while locating for Cleopatra.’ Surprisingly, in his diary Burton dwells no more than this on Cleopatra and its making. Not only is it one of the most expensive films ever made — ‘it was the spectacular to end all spectaculars — and just about did’, says George MacDonald Fraser in The Hollywood History of the World (1988) — but it also brought Richard and Elizabeth together. Both were married to other people at the outset, Taylor to the American singer Eddie Fisher, her fourth husband, and Burton to the Welsh actress, Sybil Williams, his first wife. During filming, Burton and Taylor became a ‘combination’, as Darryl F. Zanuck, head of Twentieth Century Fox, called them (in a letter to RB dated 12 November 1962). Marvellous spectacle, not at all bad, is as much as Burton can say overtly about the movie, adding, ‘My lack of interest in my own career, past present or future, is almost total.’ Not totally total, then, but almost, if we take him at face value, and maybe we should do a little more — or less — than that, and to be fair, Cleopatra (1963) itself is far from uninteresting.

Fraser’s comment refers to Cleopatra’s reputation as the movie that killed off the big budget Hollywood pre-digital historical epic for good, its problematic production nearly bankrupting Twentieth Century Fox. Although it was the highest-grossing film of 1963 and one of the best earners of the 1960s as a whole, such were its costs that it took until 1973 just to break even. Elizabeth Taylor had been a Hollywood star since 1944’s National Velvet and her fee for Cleopatra began at an unprecedented one million dollars and ended up at seven million. Filming started in the autumn of 1960 at London’s Pinewood Studios, but bad weather and Taylor’s near-fatal pneumonia yielded hardly any footage worth using despite more millions in expenditure. By September 1961, Rome had become the main location and Joseph L. Mankiewicz had taken over as director from Rouben Mamoulian, Rex Harrison had replaced Peter Finch as Julius Caesar, and Burton had been hired to succeed Stephen Boyd in the role of Mark Antony.

These changes did not stop the project’s troubles, far from it. There were more delays and escalating expenses. Originally conceived in 1958 as a B-movie costing under a million dollars, a remake of the studio’s 1917 version, by the end of 1961 Jack Brodsky, assistant publicity manager for Twentieth Century Fox, wrote that twenty-five million dollars was a more likely outlay. Right up to the end of filming, extravagance was a hallmark, with Zanuck talking of ‘investigating shooting these brief episodes [required because of drastic edits to the movie’s running time] in either Yugoslavia, Hungary, or Spain,’ adding, ‘Hungary has promised us 700 Cavalrymen.’ Estimates of the ultimate budget vary between forty and sixty-five million dollars. The eyewitness accounts in the correspondence between Brodsky and his boss, Nathan Weiss, published as The Cleopatra Papers (1963), tell of fabulous and magnificent sets ‘beyond description, particularly the Forum which is bigger than the original and about 100 times as expensive.’ It was reported that the demands of the production caused a shortage of building materials throughout Italy. Brodsky’s impression on arriving on location in Rome was of ‘chaos, organised chaos, but chaos nevertheless.’

The short, turbulent life of Cleopatra VII (69–30 BC), ruler of Egypt, the last queen of the Ptolemaic dynasty, has inspired a rich variety of movies, including three films in the silent era (1912, 1917, 1928), Cecil B. DeMille’s epic of 1934, and Gabriel Pascal’s 1945 version of George Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra. The 1964 parody, Carry On Cleo, used the sets left behind at Pinewood by the Fox production, and boasted Sid James wearing one of Burton’s actual costumes and Kenneth Williams as Caesar delivering the finest line of the entire Carry On series, ‘Infamy, infamy, they’ve all got it in for me!’ (Later voted the best one-line joke in film history, beating even Life of Brian’s ‘He’s not the Messiah, he’s a very naughty boy!’).

Cleopatra post-Burton/Taylor also includes Charlton Heston’s 1972 version of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, and, lest we forget, three Asterix movies (1968, 1976, 2002).

For a moment, there was also the tantalising prospect of Sigmund Freud’s Cleopatra movie. On a trip to Europe in 1924, the Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn made an offer of 100,000 dollars to Freud in return for his involvement in either writing or advising on a motion-picture depiction of great love stories of history, beginning with Antony and Cleopatra. The invitation was curtly refused. In his 1957 biography, Ernest Jones says that Freud disbelieved ‘in the possibility of his abstract theories being presented in the plastic manner of a film.’

The sources for Fox’s Cleopatra were not Shaw, Shakespeare or Freud, not directly at least, but the works of the first/second-century historians Plutarch, Appian and Suetonius, and principally The Life and Times of Cleopatra (1957) by the journalist and novelist Carlo Maria Franzero. The screenplay was still being composed while shooting was under way in Italy. ‘The first 50 pages of the second act have just come from Mank’s pen and they’re fabulous,’ wrote Brodsky on 24 December 1961, ‘Burton and Taylor will set off sparks, and already Fisher is jealous of the lines Burton has.’ This Cleopatra is very much a film of two halves, the first being Caesar and Cleopatra, the second Antony and Cleopatra. Two three-hour movies were envisaged by Mankiewicz and there are those who still hope that one day lost footage will be unearthed and a six-hour ‘Director’s Cut’ version released.

By the start of 1962, shooting of the Caesar/Rex Harrison part was nearing completion and, in the last week of January, Burton and Taylor played their first scene together. In time, Brodsky and Weiss realised that the central and added ingredient that was to help make Cleopatra ‘the most publicised film in motion-picture history’ had landed, but at first they were nervous. In a letter from Rome to Weiss in New York dated 15 February 1962, Brodsky says, ‘It’s no rumour, no guesswork, about what Burton is doing to Taylor. It’s plain fact. It started about three weeks ago and is now the hottest thing ever. It seems that Fisher found out about it and started squawking, so Taylor said, quote, I love him and I want to marry him, unquote.’ The production team was worried that the affair would turn public opinion against Taylor and ruin the movie’s reception, and wanted ‘to bottle it up as long as we can’, as Brodsky put it. Eddie Fisher had been the husband of Taylor’s close friend, Debbie Reynolds, but when Taylor’s third husband, Mike Todd, died in a plane crash, Fisher, in the memorable words of his daughter, Carrie Fisher, ‘consoled Elizabeth with his penis’. The studio people feared that Taylor’s reputation could not endure another scandal. But bottle it up they could not. When the production moved to Ischia in June 1962 for the Actium sea-battle sequences, Burton and Taylor flew in together to the heliport five minutes away from their respective suites on the same floor of the Regina Isabella, while, as an exasperated Weiss testified, ‘the paparazzi were springing out of every bush, zooming past us on motorcycles, and generally creating pandemonium.’

The Burton/Taylor combination frames how we watch Cleopatra. For a full ninety minutes we anticipate our first sight of the pair on screen together. Zanuck objected to the idea of splitting the movie into two parts because he believed that no audience would show up for the first part, from which Burton is mostly absent. When it arrives, the second act is not diminished by our incapacity to disentangle the dual fated love dramas, Antony and Cleopatra, Burton and Taylor. In his extensive article for Vanity Fair in 1998, David Kamp tells of how the scene in which Cleopatra vents her anger on learning that Antony had married Octavia was filmed on the same day that Burton announced to the press that he would never leave his wife, Sybil: ‘Taylor went at it with such gusto that she banged her hand and needed to go to the hospital for X-rays.’

In line with Zanuck’s wishes, the two parts were edited into one four-hour film, thereafter cut even more severely to just over three hours. Using publicity photos and the original six-hour script, James Beuselink, in an article for Films In Review published in 1988, assessed what went missing, which included passages that were key to the narrative and to the motives and character development of Cleopatra, Antony and Caesar. However, the subsequent four-hour 50th anniversary high-definition restored edition (2013) of the movie is a stunning viewing experience.

Available on DVD, Blu-ray and streaming services, in 1080p resolution and high-quality audio, the movie looks and sounds brilliantly vivid and clear. It’s true that to a modern viewer acclimatised to swooping cameras and fast editing, Cleopatra is a befuddling and stagy encounter with the epic genre. It doesn’t entirely fit with our expectations. There are few action sequences by present-day standards, and even the grand clash at Actium seems static in comparison with twenty-first-century blockbusters. Much of the battle is narrated by onlookers instead of being shown. There is an odd tendency for some important but violent events to take place not as set pieces but off-screen — they are reported but not seen. Although both first and second acts open with impressively staged post-battle scenes, of these battles themselves we see nothing. The post-battle scenes were in fact finished late on in February 1963 in Spain, compensating for sequences previously axed by the studio, and designed to enable the narrative of the truncated version to make sense.

But there is majestic spectacle. In particular, Cleopatra’s procession into Rome is a hypnotic, stupendous marvel peopled by six thousand extras (real not CGI people, naturally), and featuring Cleopatra and her son atop a huge black mobile sphinx pulled by three hundred Nubian slaves. The sets are indeed fabulous and magnificent, and the orchestration of the crowd scenes is remarkable.

The 1963 Cleopatra herself also looks stunning. Her jet-black hair and vibrant eye make-up — thick feline eyeliner with blue shadow from her lashes to eyebrows — heightened the style of previous Cleopatras and created a stir even as the film was in production. Revlon marketed ‘The new Cleopatra Look’ a year before it opened . Taylor was in the habit of wearing her Cleopatra make-up, which she applied herself, after she left the set for the day, and press photos sparked a fashion trend. The trend developed further into something more meaningful. What the look signified can be gauged from the following connections: Andy Warhol’s Liz as Cleopatra compositions of 1963; David Bowie considering adopting the Cleopatra guise around the time of Hunky Dory (1971); Marc Bolan using permutations of the Cleopatra make-up in television appearances in 1975–6; and Siouxsie of the Banshees thereafter setting it as the Goth template. Liz Taylor’s Cleopatra eyes signify the exotic outsider — glamorous, rebellious, defiant, literally extra-ordinary.

The performances of the film’s principals are never less than engrossing. Rex Harrison’s Caesar comes across at first as an old-style schoolteacher with a taste for innuendo who just happens also to be a mastermind of political and military strategy. Several times he addresses Cleopatra as ‘young lady’, and on meeting Pothinus he delivers a line worthy of Carry On Cleo, ‘Lord Chamberlain and chief eunuch to King Ptolemy. An exalted rank. Obtained not without certain, shall we say, sacrifice.’ But all of this is in the script, written by Mankiewicz in a style that Weiss describes as ‘a contemporary language which is neither colloquial, which would be silly, nor too stately, which would be antique.’ One gets used to it. In contrast, Antony’s dialogue in the second half requires tormented emotion, and Burton gives it plenty. The first half of the film presents Antony as a loyal, supremely adept military commander with an impetuous, hedonistic streak. In the second half, he is a tortured, crazed lover with a perpetual glass of wine in his hand. The transition seems too sudden and clumsy, and likely would have been tempered by the lost footage. The change in Cleopatra is less jarring. Throughout, Taylor conveys both calculated cunning and emotional openness. In the first half, her political scheming is in the ascendancy, but gradually this is overpowered by passion. Hers is the most cinematic performance of the production. Burton’s and Harrison’s portrayals have that whiff of the British stage about them, and the film’s reliance on dialogue and fondness for (magnificent) interior sequences gives it a relatively theatrical feel. Burton’s 1971 diary entries indicate his irked susceptibility to the view that movie acting was secondary to the theatre. He talks of the Press’ opinion that ‘I had dissipated my genius etc. and “sold out” to films and booze and women… by no means dull but by all means untrue’ (15 August 1971). Compared with Burton and Harrison, Taylor is given more opportunity to demonstrate the fantastic telepathic power of cinema. In the first half especially, there are moments when the camera merely lingers on her silent face. She and her director knew what Sigmund Freud disbelieved — that the motion-picture camera can read minds by dwelling on an expression and the movie screen can transmit thoughts mutely. Roddy MacDowall as Octavian is also creepily good at this. Yet it is Burton who wordlessly achieves the movie’s killer punch with his back to the camera, as he slumps to the deck the moment he realises fully what he has done in fleeing Actium.

And for any Freudian with access to Burton’s diary there is another moment of recognition in one apparently humdrum line of Antony’s near the start of the second part: ‘I wish I had not drunk so much today.’ Compare this with the diary entry of 16 August 1971:

E is sitting opposite me having her “breakfast” consisting of vodka and orange juice. A habit she picked up from me in my drinking days. A good start to the day if confined to one. In my case, sadly it had become as much as three and even more if there was anyone game enough to join me. A bottle before lunchtime was by no means unusual and a pleasant but ruined morning behind me.

My thanks to Katrina Legg, Stacy O’Sullivan, Susan Thomas and Sarah Thompson of the Richard Burton Archives, Swansea University.

Rob Penhallurick is the author of Studying the English Language and Studying Dialect (both published by Macmillan International), and co-author of Welsh English (De Gruyter).

Read last week’s Becoming Richard Burton essay here.