Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ paintings are represented in all the main public collections in Wales, as well as others in the United Kingdom, and his artist’s books are found in libraries internationally. A retrospective exhibition comprising some 200 works from across the artist’s career loaned from public and private collections was held by the National Library of Wales in 2011 to coincide with his sixtieth birthday. A substantial multi-author book devoted to his work was published by Lund Humphries in 2011, in which Simon Callow called him ‘one of the most individual and complete artists of our time’.

Clive Hicks-Jenkins: In 2015 I began a collaboration with Daniel Bugg of the Penfold Press. The Press specialises in making screen-prints, a process I had no experience of, my previous printmaking having been limited to making the occasional lino-print. None of that deterred Dan, who was confident he could guide me through the processes of screen-printing. I cut my teeth on a trial screen-print of a Staffordshire pottery group. Man Slain by a Tiger turned out so well that Dan produced the print in an edition of thirty-five that has since all but sold out. That was preparatory to the big project, which takes as its inspiration Simon Armitage’s 2007 translation of the epic medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I was so impressed by Armitage’s version that I’ve been making paintings on the theme since reading it. Between us Dan and I hatched an idea for a fourteen-print series based on the poem. The prints would be made over two-to-three years, and the plan was to offer each print as it was completed. The editions would be seventy-five prints per title in the series. We’ve worked faster than we’d anticipated, and having reached nearly the halfway point with six prints completed, we’re celebrating with an exhibition at the Martin Tinney Gallery titled Gawain and the Green Knight: Clive Hicks-Jenkins and the Penfold Press.

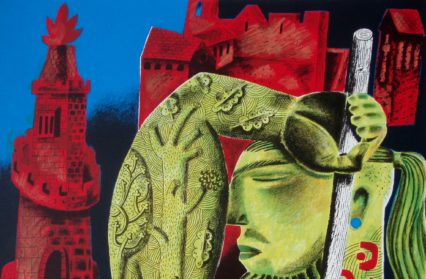

The Green Knight Arrives is the second print in the series. It’s Christmas at Camelot, and with King Arthur’s court gathered for the festivities, the arrival after dark of an unexpected and unusual guest is perhaps the most spectacular entry of a character in the history of English literature. The uninvited Knight rides into the court. He’s a giant of a man and in all his parts – hair, beard and skin – he is green. Even his horse is green. He bears a fruiting holly branch and carries a mighty double-headed axe. He proclaims he has come to throw down a challenge to the King, but in the custom of the day the challenge may be taken by any champion Arthur nominates. Young Gawain, the King’s nephew, steps forward. The Green Knight’s challenge is implausibly simple. He will stand and take a blow to his neck that Gawain will deliver with the double-headed axe, on the understanding that in a year’s time, Gawain will stand and take the return blow from the Green Knight. No threat at all then, as the Green Knight’s head will be parted from his body by Gawain’s blow, and that will be the end of that. But this is a Green Knight, and he comes at the magical turning point of the year when things might not unfold in the expected way. Well, we didn’t think they would, did we?

The moment I chose to show is one not described in the text. Here’s the Green Knight outside the doors of Camelot, just before he makes his entrance. It’s a portrait. We’re in closeup. His eyes are closed as he readies himself for what lies ahead. What he’ll undergo is not in the normal way of things. All the rules of nature are about to be broken. That’s going to take deep reservoirs of fortitude, even for a giant of a man whose colour is unusual. He steadies himself.

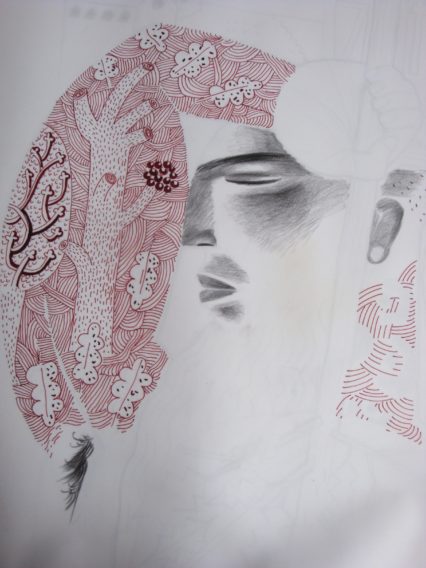

To make the image, Daniel Bugg had to print it in layers. Screen-printing requires the squeezing of ink through a fine mesh stretched across a frame. The mesh is treated so that ink can only pass through the required areas. You can think of it almost as a stencil, and there has to be a stencil for every colour in a print. So my job is to provide Dan with layers of artwork that will assemble into a finished image. To produce these, I work on transparent plastic sheets using specially formulated paints, crayons (very greasy) and fibre-tip pens. I don’t work in the colours that the print will be made in. There’s no need. I use a limited palette of black and red that shows well enough through the layers of plastic for me to get an impression of what the drawings are going to look like when printed on top of each other. What concerns me most at this point is the composition and the quality of the mark-making, although of course I have a plan firmly in my head of what I want the colours to be. Once I’ve produced all the layers for the print, Dan ‘exposes’ them so that they’re reproduced in the finest detail onto the mesh screens. Once done, the printing can begin. It’s never straightforward. Colours are mixed, proofed and remixed. Sometimes the order of printing is changed. Some colours are opaque and some transparent, and there can be unexpected effects. It’s a long process of trial and error. We discuss every stage of the making of a print until we arrive at what we set out to achieve. I’ve had to learn to think differently about image making. The process is not at all what I’m accustomed to when working at an easel making paintings. With a painting, each layer of brushwork obscures most of what’s beneath. With a print, all the layers show. There’s nowhere to hide!

To make the image, Daniel Bugg had to print it in layers. Screen-printing requires the squeezing of ink through a fine mesh stretched across a frame. The mesh is treated so that ink can only pass through the required areas. You can think of it almost as a stencil, and there has to be a stencil for every colour in a print. So my job is to provide Dan with layers of artwork that will assemble into a finished image. To produce these, I work on transparent plastic sheets using specially formulated paints, crayons (very greasy) and fibre-tip pens. I don’t work in the colours that the print will be made in. There’s no need. I use a limited palette of black and red that shows well enough through the layers of plastic for me to get an impression of what the drawings are going to look like when printed on top of each other. What concerns me most at this point is the composition and the quality of the mark-making, although of course I have a plan firmly in my head of what I want the colours to be. Once I’ve produced all the layers for the print, Dan ‘exposes’ them so that they’re reproduced in the finest detail onto the mesh screens. Once done, the printing can begin. It’s never straightforward. Colours are mixed, proofed and remixed. Sometimes the order of printing is changed. Some colours are opaque and some transparent, and there can be unexpected effects. It’s a long process of trial and error. We discuss every stage of the making of a print until we arrive at what we set out to achieve. I’ve had to learn to think differently about image making. The process is not at all what I’m accustomed to when working at an easel making paintings. With a painting, each layer of brushwork obscures most of what’s beneath. With a print, all the layers show. There’s nowhere to hide!

Gawain and the Green Knight: Clive Hicks-Jenkins and the Penfold Press by Clive Hicks-Jenkins

The Martin Tinney Gallery, Cardiff

Thursday 8th Sept – Saturday 1st Oct, 2016

You might also like…

In the latest in our series looking at the breakthrough work of artists, French-Quebecker artists Valériane Leblond opens up about her attachment to the Welsh landscape, her technique, and her development as an artist.