A common rhetorical device used by politicians over recent years has been to begin a sentence with ‘The people of this country want/ don’t want’ as if they are speaking for us, or a large section of us. It gives what they are saying the appearance of legitimacy, an illusion of being in touch with the electorate. Despite the fact that the largest party in the recent General Election, the Conservatives, was supported by less than a quarter of eligible voters.

That politicians have been able to get away with this for so long has emboldened them to become more remote from those who they purport to represent, with party leaders being transported from event to event inside a bubble of security and people who agree with them; with other so-called ‘heavyweight’ politicians being equally cosseted within the Westminster Village. This has led to the assumption by many that they really were representing their constituents, and that a broadly political status quo was the most likely; and certainly the most comfortable.

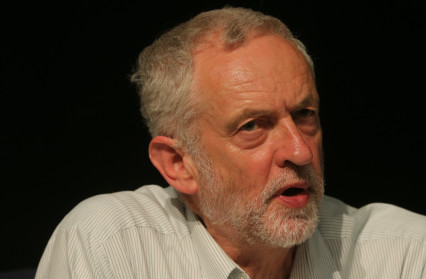

Since the election of Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader, however, this assumption can no longer be relied on. Winning on the back of an extraordinary mass movement of individuals, of voters who no longer felt they were being listened to, Corbyn has acted as a catalyst for an unprecedented amount of debate over what we can assume about politics and our society, beginning with the sheer scale of his victory.

Part of that sense of disconnection also lies with the assumption that many of the arcane rituals within our society should continue without being questioned. Whether or not one agrees with Corbyn’s views on the monarchy and militarism, we need to question them as a society on a regular basis. We have seen, in an increasingly hysterical right-wing media this week, how people who are anti-monarchy and pacifist are somehow regarded as being outside the mainstream (despite their numbers being roughly similar to those who voted Tory in the General Election). It is as if the freedom to stand against such assumptions should not be cherished as well.

Surely we need to ask why we unquestioningly accept how we can be patriotic about the above, but do not question why our media, utilities, famous brands, football clubs and public services such as schools and much of the NHS are in the hands of companies controlled by people beyond our shores. We really do not seem that bothered that the Chinese are buying into our nuclear power stations.

Arguably nowhere is this disconnection between politicians and the people greater than with Parliament itself. Here we have the absurd spectacle where it is deemed acceptable that those who seek to represent us can bray like infants doing animal impressions; yet incoming SNP members are admonished for applauding. This is an absurdity that Corbyn has already begun to address with his new approach to Prime Minister’s Questions, which needs to be the thin end of the reformist wedge if we are to get a Parliament that gets back in touch with the people.

Corbyn’s win has also begun to address some of the political assumptions about ‘what the people of this country want’. Principal amongst this is that we were happy with the neo-liberal consensus that has persisted virtually unchallenged amongst political leaders for the last twenty years. This is a consensus that has found its latest home in the politics of austerity. This is politics that is dressed up as essential, but is actually at least as extreme as anything that the new Labour leadership has come out with. A politics that states that we need to slash public services for the vulnerable and remove benefits for those who are already struggling (and abstaining in the Welfare Bill was surely the final nail in the New Labour coffin, the first nail being the invasion of Iraq). A politics that is requiring government departments to nearly halve their size over the course of this Parliament.

If we want to see how politicians have been wrong-footed by Corbyn’s election we need look no farther than some of the biggest losers in the rise of austerity politics: young people. Being left out of the increases in the so-called ‘living wage’, made to pay more and more for their education, and priced out of the housing market (including the rental sector) are just three ways in which those under 25 have been adversely affected by the policies of successive governments. Add to this an arrogant disregard for the consequences of climate change and no wonder that young people are now overturning the assumptions of political leaders that they were uninterested in politics by supporting a leader who comes from outside of the political establishment that has let them down so badly.

Right across the political spectrum we need to see assumptions being questioned. We are coming to see that refugees can no longer be kept at arms length from our shores, and that the rise in inequality cannot go on without those at the bottom at some point waking up to the reality of their situation. For many, the old order should no longer be assumed to prevail.

We live at a time of immense change, much of which we are being marched towards by being encouraged to make blind assumptions. Corbyn has already begun to challenge those things in a way that has not been done for decades. If he achieves nothing else he will have already done us a great service in generating debate in areas where we have assumed none was to be had. However, he has a lot of work to do to convince enough people that he can lead the country in a way that can bring us security and stability. It is one thing to foster a debate, it is quite another thing to sustain it and win it.

For now at least we can no longer assume that all politicians are the same, and they can no longer assume what we want.