In our final presentation from our partnership with Cardiff University’s Roald Dahl Conference 2016, Željka Flegar explores the intricate ways in which Dahl played with and championed childlike language, and how it made him one of the most famous and adored writers for children for generation after generation.

When contemplating Roald Dahl, and particularly his writing for children, what inevitably comes to mind is the statement made by Jerry Griswold in Feeling Like a Kid (2006) that “in preferring certain authors and works, while ignoring many others, the young confirm that there are a chosen few who can speak to them where they are. Simply said, the great writers for children know – and their stories speak of and reveal – what it feels like to be a kid”. A testament to this is Dahl’s immense popularity to this very day. He is ever present in the media as “UK’s top author” (BBC News 2000), has beaten “Rowling as young adult’s favourite author” (The Guardian 2007), “Enid Blyton and J. K. Rowling to top children’s writer” (Marris 2014), and was even “voted best author in primary teachers survey” (BBC News 2012). The Norton Anthology of Children’s Literature describes him as “…one of the most successful writers of children’s books of all time” (Zipes et al. 359), and it is overall strikingly apparent that he has done for children’s literature what could have been accomplished only by a selected few.

Roald Dahl’s style was impeccably unique and resulted in a specific type of expression that is particularly evident in the recent publication of the Oxford Roald Dahl Dictionary (2016). He was notorious for bending rules and upsetting the order of things, thus provoking even the charges of “vulgarity, fascism, violence, sexism, racism, occult overtones, promotion of criminal behaviour” (Culley 59), as well as the strongly divided adults’ response to his work (Watkins and Sutherland 306-7). As such, Roald Dahl was the most extreme and extravagant example of childlike language, the type of literary discourse that has been used by authors of children’s literature since the nineteenth century Golden Age era to communicate with their young audience and a type of expression often at odds with rules and norms prescribed by the dominant culture.

The theory of childlike language deals with the type of discourse that “unites the characteristics of imaginative play and children’s humour for the purpose of play with meaning, sound, and form of language, often resulting in novel expressions which delight and enlighten the child reader, and enrich language in general” (Flegar, “Nine Deviations of Childlike Language” 8). It was developed based on the foundation of (post)structuralist theories, theories of children’s cognitive development, as well as by means of a qualitative overview of some of the most influential works written for children over the course of approximately two centuries. Therefore, childlike language is characterised by its connection to the semiotic or the maternal aspect of language as defined by Julia Kristeva, which is bound to “rhythm, timbre, prosody, word-play, and even laughter” and further discussed in the context of poetic language in John Morgenstern’s account of the language of children’s literature in “Children and Other Talking Animals” (2000).

I argue, however, that children being new to the entry into the realm of language, or the symbolic, do not strive for the symbolic, but tend to oscillate between the two realms quite effortlessly. Childlike language, therefore, is also characterised by deviation from the norm, the “making and breaking of discourse” or “the tendency of the semiotic … to constantly seek to dissolve the sign back into the body” (Morgenstern) in order for readers to “observe the rules for ordering the real world by breaking them” (Cunningham).

The third aspect of childlike language is its creative or regenerative quality bound to the concept of the carnivalesque as conceived by Mikhail Bakhtin in Rabelais and His World (1965), which is, according to John Stephens, used in children’s texts to “interrogate official culture” and very broadly, by means of universal and ambivalent laughter characterized by “regenerative ambivalence” (Bakhtin) used to generate new modes of expression. In accord with children’s cognitive development, childlike language is “perceptually bound” (Strassburger and Wilson) and addresses children’s affinity for “playing with logic and content, violating the rules of language with reinterpretations and distortions, with exaggerations, combinations of the uncombinable, concoctions and collages – either by means of their own creations or by adopting given parameters” (Neuβ). Childlike language is, therefore, characterized by deviations in lexis, phonetics, semantics, orthography, and grammar, and includes the subversive and playful use of onomatopoeia, sound patterns, puns, riddles, orthographic alterations, portmanteau words, nonsense, hyperbole and neologisms. All of these deviations are contained in the work of Roald Dahl who provided children with an authentic, playful, subversive, and “vulgar” voice.

Accordingly, Roald Dahl utilised all the aforementioned elements of childlike language. In this particular excerpt from The Witches (1983) we see Dahl’s use of prosody, onomatopoeia, sound patterns, as well as interventions in orthography and phonetics (for it somewhat begs to be read outloud):

Down vith children! Do them in!

Boil their bones and fry their skin!

Bish them, sqvish them, bash them, mash

them!

Brrreak them, shake them, slash them, smash

them!

Offer chocs vith magic powder!

Say ʻEat up!ʼ then say it louder.

Crrram them full of sticky eats,

Send them home still guzzling sveets…

Semantic deviations notwithstanding, Dahl foremostly relished in word play, where the association to the semiotic is particularly apparent in the appearance of delights such as WONKA’S WHIPPLE-SCRUMPTIOUS FUDGEMALLOW DELIGHT (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory 26) or Gumtwizzlers, Fizzwinkles, Frothblowers, Spitsizzlers (The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me 63). Often he utilised blending in the creation of portmanteau words, e.g. snozzberries = snooze + berries (CCF 104-5). Likewise, the incongruity often involved in the conception of children’s humour is evident in Dahl’s use of nonsense, a stylistic device and genre that was revived in the nineteenth century by Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll (Zipes et al. 1154) who “contributed to producing children’s literature not solely as instruction and admonishment, but as entertainment for the pleasure of the child” (Rogers 44). Dahl’s fascination with limerick, Lear’s favourite poetic form, is evident in the following example from The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me:

‘My neck can stretch terribly high,

Much higher than eagles can fly.

If I ventured to show

Just how high it would go

You’d lose sight of my head in the sky!’

Incongruity resulting in humour spans across Dahl’s entire opus, producing deviations such as:

[…] Supervitamin Candy [which] contains huge amounts of vitamin A and vitamin B. It also contains vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin F, vitamin G, vitamin I, vitamin J, vitamin K, vitamin L, vitamin M, vitamin N, vitamin O, vitamin P, vitamin Q, vitamin R, vitamin T, vitamin U, vitamin V, vitamin W, vitamin X, vitamin Y, and, believe it or not, vitamin Z! The only two vitamins it doesn’t have in it are vitamin S, because it makes you sick, and vitamin H, because it makes you grow horns out of the top of your head, like a bull…

The appeal of nonsense that Dahl frequently uses is what Jennifer Cunningham (2005) elaborates on by means of Paul McGhee’s (1979/2002) five-stage-model of humor development, beginning with a child being able to perceive incongruity during infancy (stage 1), the ability to produce incongruity nonverbally as a toddler in stage 2 and then verbally in childhood by, for example, misnaming objects or actions, followed by playing with words in stage 4, and riddles and jokes in stage 5 as the child begins to seek a resolution to incongruity (104). Incongruity universally marks the development of every human being and is, therefore, readily perceived and explored.

However, the most notable feature of Dahl’s writing, and one that needs to be particularly emphasised, is exaggeration. Dahl’s unrestrained use of hyperbole inevitably leads to taboo, grotesque, gore, and, laughter. Note the full description of Headmistress Trunchbull in Matilda (1988):

Miss Trunchbull, the Headmistress, was something else altogether. She was a gigantic holy terror, a fierce tyrannical monster who frightened the life out of the pupils and teachers alike. There was an aura of menace about her even at a distance, and when she came up close you could almost feel the dangerous heat radiating from her as from a red-hot rod of metal. When she marched – Miss Trunchbull never walked, she always marched like a storm-trooper with long strides and arms swinging – when she marched along a corridor you could actually hear her snorting as she went, and if a group of children happened to be in her path, she ploughed right on through them like a tank, with small people bouncing off her to left and right. Thank goodness we don’t meet many people like her in this world, although they do exist and all of us are likely to come across at least one of them in a lifetime. If you ever do, you should behave as you would if you met an enraged rhinoceros out in the bush – climb up the nearest tree and stay there until it has gone away. This woman, in all her eccentricities and in her appearance, is almost impossible to describe, but I shall make some attempt to do so a little later on.

In creating characters and situations that were incredibly striking, Dahl followed the advice of his main protagonist to “[n]ever do anything by halves if you want to get away with it. Be outrageous. Go the whole hog. Make sure everything you do is so completely crazy it’s unbelievable” (Matilda). The random violence, expressions, methods and deviations of Miss Trunchbull are so wholly unbelievable that they are basically funny. Not surprisingly, the word REVOLTING (in capital letters) instantly comes to mind as well. Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes (1982), adaptations of classic fairy tales in rhyme, feature Little Red riding Hood who “whips a pistol from her nickers” and shoots the Wolf, the Prince who “chops off heads!”, or Goldilocks being a “brazen little crook”.

Interestingly enough, such stylistic identity is a common feature of traditional fairy tales as “stories of human experience told in primary colors” (Tunnell and Jacobs). The flat characters, cruel vengeance, grotesque villains and stylistic simplicity are all elements of classic fairy tales, which in Dahl’s case explains the charges of vulgarity aimed his way, but also his universal appeal (Flegar, “The Alluring Nature of Children’s Culture”).

The likewise striking aspect of Dahl’s writing is its neologistic quality in accord with the transformational, regenerative and perennial nature of childlike language. The use of childlike language frequently results in the invention of fantastic secondary worlds, creatures, objects, customs, procedures, or what Jann Lacoss in the context of the Harry Potter phenomenon calls a “specialized lexicon”. In Dahl’s case the innovative use of language particularly reflects on lexis, the obvious example being the specialised Oxford dictionary published in his honour, featuring words from aardvark to zozimus (OUP). Many of those are derived from Gobblefunk, the language that Dahl invented in his novel The BFG (1982), which were created by means of blending and mixing up words and phrases, such as delumptious, dinghummer, catasterous disastrophe or deaf as a dumpling (see fig. 2).

Finally, all the deviations involved in the production of language according to Dahl result in a novel and humorous type of childlike expressions that is well depicted in this account of a dream from The BFG:

i has ritten a book and it is so exciting nobody can put it down. as soon as you has read the first line you is so hooked on it you cannot stop until the last page. in all the cities people is walking in the streets bumping into each other because their faces is buried in my book and dentists is reading it and trying to fill teeths at the same time but nobody minds because they is all reading it too in the dentist’s chair. drivers is reading it while driving and cars is crashing all over the country. brain surgeons is reading it while they is operating on brains and airline pilots is reading it and going to timbuctoo instead of london. footbal players is reading it on the field because they can’t put it down and so is olimpick runners while they is running. everybody has to see what is going to happen next in my book and when i wake up i is still tingling with excitement at being the greatest riter the world has ever known until my mummy comes in and says i was looking at your english exercise book last nite and really your spelling is atroshus so is your puntulashon.

The grammatical, semantic, or orthographic deviations are there to provide a child with the opportunity to deconstruct language and construct it according to their own liking, to violate rules of speech and conduct in order to learn them, and to accumulate power.

The features of childlike language, however, appear in Dahl’s writing for adults and his cross-over fiction as well, as in this excerpt from the short story “Georgy Porgy” (1960):

As you might guess, I am having to keep entirely to myself and to take no part in public affairs or social life. I find that writing is a most salutary occupation at a time like this, and I spend many hours each day playing with sentences. I regard each sentence as a little wheel, and my ambition lately has been to gather several hundred of them together at once and to fit them all end to end, with the cogs interlocking, like gears, but each wheel a different size, each turning at a different speed. Now and again I try to put away a really big one right next to a very small one in such a way that the big one, turning slowly, will make the small one spin so fast that it hums. Very tricky, that.

Dahl’s childlike expression is present in all his writing. However, he was very aware of his audience. Although in his writing for adults he uses hyperbole, grotesque (e.g. metamorphoses), unexpected twists, subverted expectations, taboo and word play, he pays particular attention to the linguistic aspect of the text, or the symbolic, in his texts for children. The reason for this is primarily historical and cultural. Dahl’s use of childlike language reflects the fact that he “aligns with the child reader, entirely takes away the adult authorial power to caution and teach moral lessons and literally annihilates the adult influence in the creation of children’s texts,” and thereby “metaphorically ‘flips off’ adult culture and acknowledges the power of the twentieth-century child consumer” (Flegar, “The Alluring Nature of Children’s Culture”). In this sense Dahl is the embodiment of changes that took place in the second half of the twentieth century that gradually demarginalised children’s culture and made it appealing to everyone.

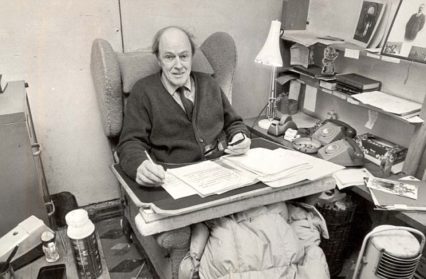

Dahl’s relationship to language most likely originated in his family and circumstances. He was born in Llandaff, Cardiff, Wales, into the Norwegian household of Harald Dahl and Sofie Magdalene Dahl where he developed a significant attachment to his Norwegian roots and folklore (Zipes et al.). He recalled his visits to Norway in his autobiography Boy (1986), thus:

All my summer holidays, from when I was four years old to when I was seventeen (1920-1932), were totally idyllic. This, I am certain, was because we always went to the same idyllic place and that place was Norway. Except for my ancient half-sister and my not-quite-so-ancient half-brother, the rest of us were all pure Norwegian by blood. We all spoke Norwegian and all our relations lived there. So in a way, going to Norway every summer was like going home.

Because his parents maintained a relationship to their heritage in many ways, but mainly by speaking Norwegian at home, Dahl had equal command of both English and Norwegian, making him a simultaneous or true bilingual (Harley). Research over the past few decades has revealed that bilinguals are endowed with a cognitive/mental flexibility because they have two sets of vocabulary for one object, providing them with a higher capacity to generate novel ideas (Ahtola; Bialystok; Baker). The arbitrariness between meaning and form allows them to think divergently, while at the same time experience the intensity of being simultaneously exposed to two different cultures. It is very likely that Dahl’s cognitive flexibility contributed to his subversive and playful use of language, even quite early on, as the following school report suggests, “I have never met a boy who so persistently writes the exact opposite of what he means. He seems incapable of marshalling his thoughts on paper” (Nudd). Dahl’s perception of linguistic sign as arbitrary, most likely influenced by his bilingual upbringing, as well as his keen sense for social interactions, which were blown out of proportion and conceptually subverted, allows for a deeper understanding of his style. Roald Dahl genuinely knew what children liked and he had the means to address that.

Years after his death Dahl’s literary and linguistic influence remains. To honour the centenary of his birth on September 12, 2016, the Oxford English Dictionary updated the latest edition with six new words associated with Dahl’s writing (Dahlesque, golden ticket, human bean, Oompa Loompa, scrumdiddlyumptious, witching hour) and revised four phrases that had been popularised by Dahl’s tales (frightsome, gremlin, scrumptious, splendiferous) (Dent; Cooper). Especially highlighted by Vineeta Gupta, head of children’s dictionaries at Oxford University Press, was his use of old words, rhymes, malapropisms and spoonerisms as a linguistic method to his “mad use of language”.

Much like Roald Dahl’s contribution to literature, childlike expression is characterised by subversiveness, empowerment, experimentation, freedom and justice. From the beginnings of children’s literature that were bleak, indoctrinating and didactic, children’s culture has come a long way owing to individuals like Dahl who perceived children as a population with specific preferences and tastes. Since the Golden Age childlike language has permeated mass media and influenced the global culture in a profound way, mostly by means of advertising and media adaptations of literary works. Roald Dahl as a representative example of this playful, subversive and regenerative expression has provided children (and adults) with a fulfilment of two very essential needs: to be entertained and amused, as well as to understand the world and their place in it (Flegar, “Nine Deviations of Childlike Language” 9). It is impossible to have read Dahl and forgotten about it. Roald Dahl was a master of his trade who manipulated language in order to delight, engage and distress. It was a technique by means of which memorable stories and characters came to life, and made us realise that ANYTHING was possible.

You might also like…

Gray Taylor takes a look at the story behind Roald Dahl’s penning of the script for Sean Connery comeback Bond movie, You Only Live Twice.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Roald Dahl | A Retrospective.

Željka Flegar was born in Osijek, Croatia, in 1978. She is currently assistant professor at the University of Osijek where she teaches courses in children’s literature, media and drama in English. Her research deals with deviation from the norm, subversiveness and the intricacies of the English language and literary discourse, such as word play, nonsense, the creation of neologisms, as well as metafictive and experimental techniques. In her recent work she ventured to discuss bilingualism of number one children’s authors, “monstrous” discourse and relations of power in fantasy literature, the improvisational nature of the literary heroes of the Golden Age, “childlike language” of children’s fiction, as well as carnivalesque adaptations of fairy tales. Her research was published in Croatia and abroad (Književna smotra, Discourse and Dialogue, Humour and Culture 1, English Language Overseas Perspectives and Inquiries, Libri & Liberi, Detskie Chtenia, The Cambridge Quarterly, International Research in Children’s Literature), she presented her papers at international scientific conferences, hosted theatre workshops and staged plays with people of all ages. She recently published the book on improvisational theatre Theatrical improvisation, language and communication [Kazališna improvizacija, jezik i komunikacija] (2016).