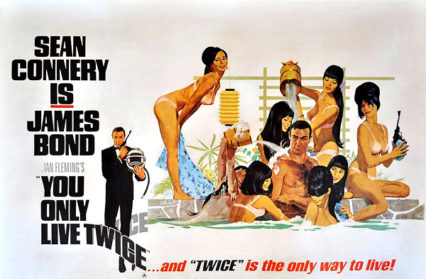

Gray Taylor takes a look at the story behind Roald Dahl’s penning of the script for Sean Connery comeback Bond movie, You Only Live Twice.

Roald Dahl; writer and creator of the Bond novels, in which suave super agent James Bond fights the forces of evil terror organisation Spectre, ably flanked by Willy Wonka of Q branch supplying our hero with exploding marshmallows and flying fizzy drinks. The character came to prominence in the ‘sixties, fighting such villainous plots as poisoning Britain’s pheasant population and unleashing huge, weaponised, organically modified fruit. The character fell out of favour because of far-fetched stories involving a coven of child murdering witches and a plot in which Bond joined forces with an amiable giant to fight a renegade group of overgrown humans.

Okay, okay so this is all happening in a parallel universe, but in 1967 we had a little taste of what that universe might have been like. (Besides that giant plot isn’t much more far fetched than the film plot of Moonraker).

In 1967, Dahl’s world and the world of Ian Fleming’s James Bond collided, as the successful children’s author was credited with the screenplay for You Only Live Twice. As a huge fan of both these worlds, You Only Live Twice has always held a special place for me in the pantheon of Bond films, in turns a frustrating disappointment hindered by production difficulties, and a huge, impressive action adventure movie that laid the foundations of every action adventure movie that followed it. As a child, I had always treated this venture with a great romanticism, two literary kings of the ‘sixties thrashing out the plot for the most exciting hero of our time. Of course, the reality is much more different; for a start Fleming was dead.

Next up in destroying the dream; Dahl wasn’t the first choice for screenwriter and was brought in at the last minute as Richard Maibaum, screenwriter of the previous Bonds, was unavailable. Dahl himself would probably not have entertained the idea of writing the screenplay had he not needed to bring in some quick income after his wife, Oscar-winning actress Patricia Neal, had become ill and was unable to work. In fact, once Dahl started work, he found Fleming’s book to be ‘tired’, ‘bad’, and ‘Ian’s worst book’. Dahl went on to say that, ‘You Only Live Twice was the only Fleming book that had virtually no semblance of plot that could be made into a movie.’ He also added, ‘I could retain only four or five of the original novel’s story ideas.’

Next up in destroying the dream; Dahl wasn’t the first choice for screenwriter and was brought in at the last minute as Richard Maibaum, screenwriter of the previous Bonds, was unavailable. Dahl himself would probably not have entertained the idea of writing the screenplay had he not needed to bring in some quick income after his wife, Oscar-winning actress Patricia Neal, had become ill and was unable to work. In fact, once Dahl started work, he found Fleming’s book to be ‘tired’, ‘bad’, and ‘Ian’s worst book’. Dahl went on to say that, ‘You Only Live Twice was the only Fleming book that had virtually no semblance of plot that could be made into a movie.’ He also added, ‘I could retain only four or five of the original novel’s story ideas.’

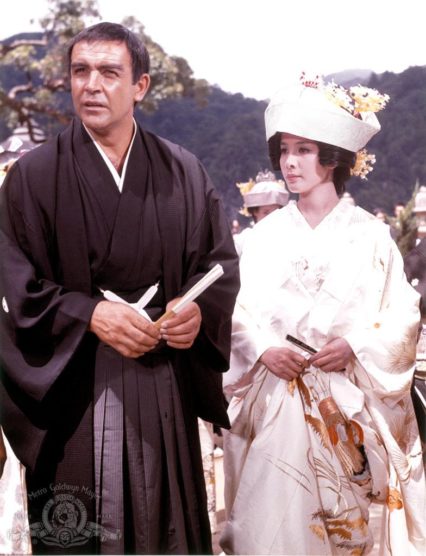

In many ways though, Dahl was perfect to tackle this difficult job. He and Fleming had been friends, serving in an elite group of spies together in 1942 on a direct order from Churchill to improve British relations with the US in order to ensure their backing in Britain’s fight against Nazi Germany. Yes, real James Bonds! In fact, Dahl had actually experienced far more action than Fleming, being wounded as an RAF pilot, and was actually far more the charismatic James Bond-type able to charm open doors that Fleming could only dream of walking through, which included hanging with FDR in the White House and sparring, both mentally and physically, with Ernest Hemingway.

Fleming seems to have admired Dahl greatly, even more so when it was Dahl who made the first foray into movies, working on a failed project with Walt Disney. Fleming is reported to have asked Dahl for help getting money for a film adaptation of Casino Royale, leading to the classic quote, ‘Money’s despicable stuff, but it buys Renoirs.’

So, what do we get from this serendipitous meeting of suave action hero and James Bond? Well, first off, Dahl captures the zeitgeist with a story of stolen spaceships, stolen in outer space no less, and dispenses of the morose, revenge plot of the book, particularly necessary because the events that led to it hadn’t happened yet in the James Bond movie world. Dahl is also aware of the potential for Bond’s world to be larger than life with the stupendous budget of the producers and the talent of designer Ken Adam, hence we have perhaps the greatest Bond set ever, Blofeld’s lair inside a volcano. This lends itself perfectly to the explosive, expansive action set-piece at the end, Dahl going for an all out gun battle that really does inform eighties action movies.

Humour had been hinted at in previous Bonds (Pussy Galore, anyone?!), but here Dahl ramps up the level of humour significantly, something that by and large, for better and for worse, subsequent Bonds would embrace. At times, the humour is almost Carry On, comedy heightened to a saucy postcard. At one point as Karin Dor pushes out her breasts, she offers Bond advice on his smoking: “Mr Sati believes in a healthy chest.” Dahl’s playfulness and lightness of touch with the dialogue here is nothing short of revolutionary for future Bonds; it certainly helped prolong the series’ popularity and longevity, as well as of course dooming it amongst critics pretty much right up to Daniel Craig strolling out of the sea with a brand new package (ooh err, matron).

Humour had been hinted at in previous Bonds (Pussy Galore, anyone?!), but here Dahl ramps up the level of humour significantly, something that by and large, for better and for worse, subsequent Bonds would embrace. At times, the humour is almost Carry On, comedy heightened to a saucy postcard. At one point as Karin Dor pushes out her breasts, she offers Bond advice on his smoking: “Mr Sati believes in a healthy chest.” Dahl’s playfulness and lightness of touch with the dialogue here is nothing short of revolutionary for future Bonds; it certainly helped prolong the series’ popularity and longevity, as well as of course dooming it amongst critics pretty much right up to Daniel Craig strolling out of the sea with a brand new package (ooh err, matron).

The action too becomes more in the realm of fantasy and this is indeed the most action packed Bond up until this point. This really does set the standard for Bond films in the guns and explosions stakes. This was the film where, as a child, I presumed that if you were shot in a film you had to fall from a great height, such is the abundance of stunt people throwing themselves off great heights. And, of course, Dahl’s imagination is in full flow in Bond’s gadget laden mini helicopter, Little Nellie, replete with rockets and flame thrower; it could probably only be beaten by a flying glass elevator.

Amongst all the fun, however, Dahl does add the cynicism that features in the fantasy of his children’s books. Here, though, we are in the very real area of world politics. There’s the aforementioned space race references, but even more telling is how Dahl writes for the American characters. Perhaps inspired by his time trying to appease and charm them during the ‘forties, the American characters here are far more pig headed than we see in other Bond movies. Felix Lighter is nowhere to be seen and the comradeship with his American counterpart is completely absent from the relationships we see. American chiefs dismiss the British as nonsense peddlers ignorantly believing that their instruments are beyond the potential for fault as they are the superior nation. Turns out the British are right all along, allowing them to smugly smile, gracious in victory.

Another cynical aspect of Dahl’s script for You Only Live Twice is that this is the film that really establishes the female characters as disposable creatures, present for Bond’s amusement, to be dispatched by the bad guys, with little regret from Bond himself. This is, of course, a characteristic of Fleming’s novels, but it is largely lacking in Maibaum’s screenplays that preceded this and it seems odd that it should be the writer of so many beloved children’s books and, in many ways, a forward thinker, that should emphasise this element.

But, really I’m nit picking at what, for me at least, is one of the very best Bond films. I truly have never noticed Connery’s apparent disinterest in being in the film, by now completely fed up with being Broccoli and Saltzman’s personal cash cow, legendarily refusing to act when Saltzman appeared on the set of this film. The imagination in You Only Live Twice is lifted to a fantastic level and without it perhaps the film’s content would have been too grim to be enjoyed, including a pool of piranha munching a woman to death, strong stuff in 1967. Dahl delivered the screenplay in eight weeks and described it as ‘the biggest load of bullshit I have ever put my hand to.’ Cubby Broccoli disagreed and hired Dahl to write the screenplay for Fleming’s Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, which Dahl less eloquently described as ‘a piece of shit.’ That time everyone agreed. But, in You Only Live Twice, Dahl not only laid down the template for the next 35 years of Bond movies, but also created the ultimate Bond, action packed to the rafters of its dormant volcano. It might be overstuffed, but as Bond says, when his attendant Japanese play things laugh at his hairy chest, “Japanese proverb say: Bird never make nest in bare tree.”

You might also like…

Why are Roald Dahl’s villainous women so monstrously evil? In the latest in the series of essays examining the work of the iconic children’s writer in partnership with Cardiff University, Samantha Velez explores the preponderance of female villains in Roald Dahl’s work.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Roald Dahl | A Retrospective.

Gray Taylor is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.