One of the side benefits of setting a slice of autobiography next to a selection of short stories – as they’ve done in this Library of Wales volume – is that the reader can often see how life can be transformed or transmuted into fiction. In this respect Dai Country acts as sort of parallel text, showing the way a novelist appropriates from his own life, much in the same way as Paul Auster’s The Red Notebook details such borrowings and appropriations.

So many episodes and details of Alun Richards’ formative years (the section of his autobiography included in this volume is mainly about childhood and ends just as his schooldays reach their final term) make it into his fiction. Take this event from the time when Richards worked as a trainee probation officer and had to interview a woman whose son had attempted to castrate himself with a cut-throat razor:

Upon discharge from a surgical ward, he was transferred to a mental hospital where I had to visit him and complete a standard form after consultation with his mother. One of the column entries asked for a statement describing the mother’s attitude to the matter in question. I think it said, ‘Attitude to the Offence’.

In the dingy almoner’s office, a little woman sat opposite me, demure in a purple hat, a fox fur; on her lapel a clutch of artificial flowers of the kind which I always remembered my grandmother wearing. She had come down to the valley to the hospital dressed in her Sunday best. For me it was a poignant moment but I adopted a breezy confidentiality as I questioned her.

‘Tell me, Mrs Williams, what do you think yourself about what Emlyn’s done?’

She smiled, a tight little smile from those purse-like lips, clasping her hands primly about her handbag.

‘What our Emlyn have done is wrong,’ she said carefully; ‘but it was on the right lines.’

And this is the way in which the self-same event surfaces in one of Richards’ short stories, namely ‘Dai Canvas’:

Once he had worked with a young lad who was too close to his mother. One day, after some traumatic adolescent experience, the lad attempted to castrate himself with a razor blade. The mother accompanied him to hospital and while she deplored the extent to which the boy had gone, she still saw virtue in his action. He had gone too far, as she said to the appalled caseworker, but it was on the right lines! And hearing the tale, Benja saw her point. He recalled it now with a smile.

There are many such interfaces between memory and story in this volume, shot through with that Richards’ panache and zest for life (I remember him offering me a G&T on an early afternoon visit but have no memory of pouring myself into a taxi when I left, although I do remember some of the stories). That badinage, that ready flair for bon mots and pithy anecdote is here in abundance, such as the comparison that suggests that ‘Like the Greeks, the Welsh enjoy their woes and they nourish them in abundance, often preferring remembering to living.’ Richards’ blue remembered hills are made up of coal waste and the vivid descriptions of the town where he grew up are full of populous sights and industrial sounds for ‘Always there seemed to be the clank of shunting coal trucks, coupling and uncoupling and, at intervals, pit whistles blew while at other times of the day the roads echoed with the clink of steel-tipped colliers’ boots, their faces black as they came up from the pit.’

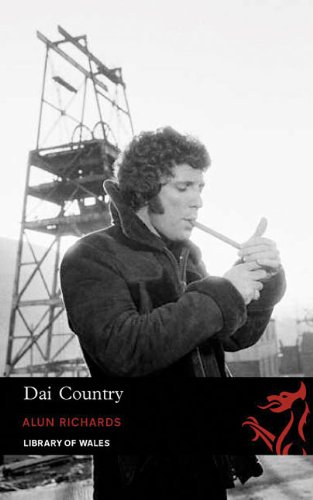

by Alun Richards

One of the strongest characters in the autobiography is the grandmother, matriarchal enough to lead one of the tribes of Israel. She feels guilty if she’s not working and has plenty of wisdom to share around, not least the fact that one should always wear clean underclothes in case of an accident, especially when visiting major English cities! ‘Suppose you were run over?’ she would argue; ‘you don’t want people to know where you’re from!’

Life for the young Alun isn’t easy. It’s a tough time economically and the shadows of war are lengthening and there are also random acts of cruelty, such as the day the teacher dishes out some gifts to his charges but realizes there aren’t enough pencils and bananas to go round. He then separates the pupils by asking all those without fathers to stand up. Getting to his feet, this becomes the public announcement of what separated Alun from others. He is the boy without a dad. It shapes him.

There are other horrible incidents, especially the rape by half a dozen of the bigger boys of a girl who ‘was not quite there’ on a school trip. It’s a terrible moment made all the more so by its casualness, and the clear lack of heed of the boys involved.

Rugby offers him a source of solace and satisfaction, even though he ‘lacked the physical coordination for excellence, but early on I sensed that there might be a place for me.’ But if rugby is one escape route then fiction is a veritable super-highway out of there, as he devours fiction omnivorously and uncritically, book after book, having to obtain extra library tickets to last him over the weekends. Crucially, while in the sixth form, he reads Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, which he describes as an ‘event’ in his reading life.

The seven stories selected to populate Dai Country are his best and best-known and will hopefully send people out to read his two full collections. There are glamorous women seducing young schoolboys, police brutalities, parables of ageing, gay accusations at the rugby club and a boxing story which fair suppurates with revenge. Collectively the stories and sample slices of autobiography allow us to spend a little more time in Richards’ company, which is never a dull thing, as he was a man he could always inject a champagne fizz into the words that tumbled out so fluidly and engagingly.