It was in his wartime Indian letters that Alun Lewis exclaimed to his parents: ‘The world is much larger than England, isn’t it? I’ll never be just English or just Welsh again!’ During that time Lewis produced some of his finest poetry: ‘I consider my poems as expressions of personal experience’ he said. These lines remind me of another poet whose personal Great War experiences produced a masterpiece that has largely been forgotten. Perhaps because it is just too ‘big’ for most anthologies!

The 1920s and 1930s – those sigh-like, ‘in between’ decades evolved into moments of contemplation for the poet. His name was David Jones and he was about to ‘transubstantiate’ his war memories into verse. In Parenthesis is complex, yet as David Blamires says: ‘It is a work that communicates even before it is understood.’ It can be enjoyed on numerous levels and it is surely apt to read such a work with the hindsight of a century behind us.

In Parenthesis is not ‘just’ a poem and Jones was never ‘just’ a poet.

Let me take you back to Nant-y-Ffin in the rugged folds of the Black Mountains where a hermit works on his lettering, engraving and painting. This man is a ‘Welsh Londoner’, a veteran who dreams about the oneness of Britain, constantly seeing the legionaries on the hills and gasping at nature as it pulsates with the charged memory of its Creator. Both Jones and his friends T.S. Eliot and Saunders Lewis were aesthetically ‘sacramental’, seeing, according to Charles Moorman, ‘man and nature, seen and unseen, object and symbol as part of a total experience.’

Jones’s poetry is difficult. It might help the reader as he reads the two hundred pages of In Parenthesis is to view it through two lenses. One lens is Celtic with its historical, mythological and linguistic tints. As you look notice the shadows, or echoes, of an earlier poetry by the sixth- century war poet Aneirin who documented the Thermopylae-like defeat of the Gododdin tribe by a superior Saxon force. There are echoes from the Mabinogi too especially with that magical cauldron that rejuvenated the fallen. The second lens is Christian, especially Roman Catholic, or rather, ‘Catholic’. Both lenses are connected by the central motif of ‘rebirth’ bridging these two important traditions.

Labelling the poem as ‘just’ English or ‘just’ Welsh will simply not do. It is not even wholly ‘Anglo- Welsh’ either because although Jones is usually numbered with Laura Wainwright’s nomads ‘between two established cultural spaces’, like a nomad, he is always on the move. The reader soon realises that the poet does not set up his tent in one tradition for very long!

The narrative of the poem focuses in on the Somme Campaign from December 1915 to July 1916. It follows Private John Ball whose march from camp to trench feels like a Homeric epic. Its realism, at first, is overwhelming because not even the minutia of an ache goes unnoticed. The poem appears as a seven- part cacophony saturated with complex allusions and a myriad of voices. You will encounter obscure characters speaking a range of different languages from the old Welsh to cockney dialect with a bit of Latin rite thrown in. No wonder Thomas Dilworth said that reading the poem for the first time was ‘like clawing through gauze’!

The poem’s narrative slowly takes us to the massacre near Mametz Wood. The death of Lieutenant Jenkins is very moving and an example of that nightmarish realism that this camera-shot poetry captures:

He sinks on one knee

And now on the other,

His upper body tilts in rigid inclination

This way and back […]

Time stops. Nine or ten lines describe the gassy death. A face ‘lifts to grope the air’ like that ‘drowning’ soldier in Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum est’. His body is described ‘like a pendulum’, swinging in and out of eternity, ‘this way and back’ before dying. These flickering characters have the potential to change into Arthurian knights or Celtic warriors at any moment; they clamber through the Somme and then they are suddenly striding through Camlann. Eerily the same crows fly ‘across the evening’, cawing, waiting to feast on the fallen. It is the transformative and mythical nature of the poetry that reveals that In Parenthesis is much more than a war narrative.

Look through the Celtic lens. The use of the Mabinogi and the Battle of Catraeth fuses into a universal ritual of producing art in a wasteland situation – of making it new again. The bard has a eulogistic role as ‘rememberer’ but as Jones stated ‘the poetry of the “first bards” was concerned’ not only as eulogy but also for the ‘recalling and appraisement of the heroes in lyric form.’ We follow him. Can you hear the soldiers singing again whilst facing the apocalyptic riders?

Riders on pale horses loosed

and vials irreparably broken

an’ Wat price bleedin’ glory

Glory

Glory Hallelujah

and the Royal Welsh sing:

Jesu’

Lover of my soul… to Aberystwyth.

Not even death and all its philistinism can silence the musical nation. You can hear the commander shouting ‘Move on-get a move on-step over-up over’ as we follow the figure ‘immediately next in front’:

His dark silhouette sways a moment above you – he drops away

Into the night and your feet follow where he seemed to be.

As we follow, you encounter Aneirin; the Celtic bard is brought back in the guise of the modern Aneirin Lewis. All seems lost when you see this bardic prototype killed with ‘no one to care’ and ‘no maker to eulogize him.’ Has art been defeated? Has the war finally silenced the poets?

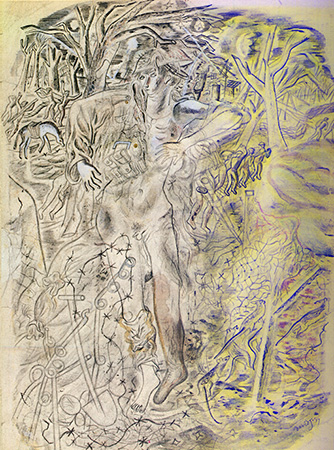

Not at all – Jones takes up the mantle. Look through the Christian lens and you begin to realise the significance of the soldiers. They are not only rejuvenated through words but they evolve into quasi-redeemers echoing Christ by triggering creativity in that dismal terrain; this is the old motif of life from death constantly pointing to that empty Judean tomb. This explains the Golgotha-like frontispiece with the soldier crucified in wire, two crossed trees both sides and the faded red trickle that seeps into the surrounding ground. Their death gave us In Parenthesis and the whole creative portfolio that emerged from the panoply of war.

We finally arrive at the Dantean conclusion – my favourite part. The mythic Queen of the Woods symbolically recognizes the goodness of the soldiers by transforming them into ‘sweet princes’ with floral diadems. The poignant episode is enhanced by the concept that all the soldiers, German and British, are ‘worthy of an intelligent song for all the stupidity of their contest’. In Parenthesis vividly portrays this by fusing the severed Germanic ‘flaxen heads’ to the ‘bent Silurian shoulders’ that lie together in the trench. Surely this is Jones’s poetic monument to the futility of war.

Jones survived. However, like Alun Lewis, the world had grown much larger that year and it would take him years to rein in all those agitated memories and write them down on paper.

This is the year of the poppy and it is a very good time to read In Parenthesis. Perhaps as you wander through the woody scenes in Owen Sheers’ Mametz you will imagine the young Jones peeping through a crack in the wall somewhere in Northern France. What did he see? He saw the peasantry celebrating mass in a barn. Maybe that moment of bliss in such an Armageddon inspired him to perform his very own poetic transubstantiation. How did he achieve this? He wrote a poem, thus creating art from a Wasteland situation.

In Parenthesis is more than ‘just’ a poem especially when the bullets are powerless against ‘this song’ and all the others.

Illustration by Dean Lewis