As I write, Welsh National Opera CEO and Artistic Director David Pountney is deep in rehearsal for WNO’s forthcoming season: ‘Liberty or Death’. His new, twin productions of Rossini’s William Tell and Moses in Egypt will spotlight the Italian composer’s addressing of serious subjects; for Rossini was not just the creator of ‘lightweight’ comedy, romance and grand operatic spectacle, but a composer whose thirty-nine operas also encompassed the exploration of social and political issues from an individual to a national level. These issues included – at the end of his career and before he retreated into silence – the right to freedom from oppression; territory more often associated with his great supposed ‘rival’, Beethoven.

Pountney’s freshness of approach and attunement to both historical and contemporary relevance is typical of a director renowned – and sometimes controversial – worldwide for his bold, visionary productions and innovative programming. This autumn, he returns to WNO hot-foot from his eleventh and final year as Intendant at the Bregenzer Festspiele; a month-long festival which annually transforms the small Austrian town of Bregenz, nestling on the shores of Lake Constance, into a hive of operatic, musical and artistic activity.

Based around the floating Seebühne (the lake stage) and Festspielhaus, Pountney’s legacy is a festival which has excelled at combining the popular and the radical with artistic and box office success (the location will be familiar to James Bond fans, as the Festival’s 2007 staging of Puccini’s Tosca became a backdrop for spectacular action sequences in Quantum of Solace). Every performance of his production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute sold out in this, its second year, to the tune of well over 200,000 visitors. But audiences for other, less obviously crowd-pleasing events were also extremely healthy – including near sell-out for an in-depth focus on the work of HK Gruber; a contemporary composer who, as Pountney notes below, has in many ways been better appreciated to date in the UK than in his native Vienna.

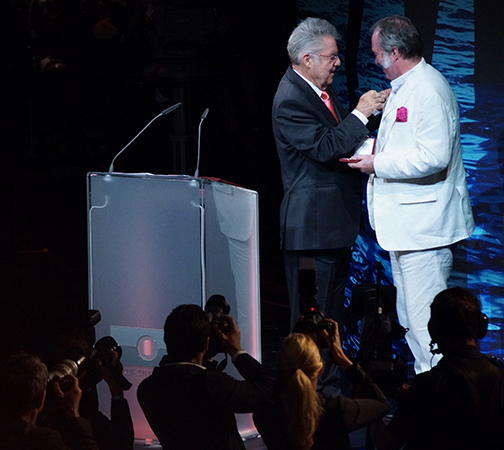

Recognition for Pountney’s achievements in Bregenz has come not only in the form of the Austrian Cross of Honour, the government’s most prestigious accolade, but with the production of a book, Der Fliegende Engländer [The Flying Englishman], edited by longstanding Festival colleagues Axel Renner and Dorothée Schaeffer. This tells the story of Pountney’s decade-plus as Intendant with an affection and appreciation that is palpable in its very title, which refers back to his first ever production at Bregenz in 1989, of Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman.

Thanks to a generous grant from Wales Arts International, I was able to visit the Bregenz Festival this summer to experience firsthand Pountney’s work within this unique European context, at the confluence if you will, of Austria with Switzerland, Luxembourg and Germany; to get a sense of how his international outlook and experience informs his work at WNO – and vice versa of course, as his association with WNO stretches back to his groundbreaking Janáček productions there of the 1970s, in co-production with Scottish Opera.

Since Pountney became Artistic Director of the company in 2011, WNO audiences have quite literally been both ‘shaken and stirred’ by his thought-provoking and entertaining themed seasons. The day after my arrival at Bregenz, he spoke with me in his office overlooking the lake stage about many aspects of his work at the Festival and beyond; about staging The Magic Flute on the lake, and about his parting theme for the Bregenz Festival this year: ‘Bittersweet Vienna’.

*

Steph Power: Running an opera festival – albeit one that takes place every year – must demand a very different approach from running a national opera company. Can you say something about the contrasts?

David Pountney: Yes, I think the main thing is that the entire purpose is different. A festival to my mind should be ‘a unique event in a unique location’ – that is the phrase I use. So the idea of a balanced programme is nonsense; actually you’re supposed to make an extreme programme. Over the eleven years, I think we’ve made more and more extreme programmes really, which is great. And sometimes, when the opportunity’s been there, we’ve made some really very stringent programming. In the Weinberg year, for example, we played twenty-three pieces by this totally unheard of composer – that’s a kind of extreme programming. [Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s extraordinary opera about Auschwitz, The Passenger, received its long-overdue world première at the Festspielhaus in 2010.]

An ‘immersive’ programming.

Right – and another phrase I use is ‘no escape’! That is, we don’t offer any Brahms and Dvořák and Schubert and all that stuff! Whereas, if you’re running a theatre that is the daily bread of a community, then you’re obliged to take a completely opposite point of view, which is to try and give a balanced programme; to offer different things to that community and give them a balanced diet. And of course the whole work rhythm of a festival is incredibly different. A festival is a kind of endless foreplay and very hectic action, whereas a theatre that’s year-round has a quite different feel about it!

I can imagine! – and has to support an in-house orchestra and chorus throughout the year and so on?

Yes. We have very low infrastructure at Bregenz really. We go from around forty employees to 1,500 over one weekend, which has all kinds of weird logistical consequences [WNO directly employs some 230 people year-round with, of course, an array of freelancers per production].

You’ve talked in the past about there being an unnecessary distinction between the serious and the popular in contemporary culture. I found a nice quote where you say, ‘the blunt separation of art from entertainment is false and irrelevant’. That feels very powerful, especially in the light of something you said in our last conversation about Schoenberg; about how, in Germanic culture, there’s been a suspicion almost of entertainment because of the Nazis having tainted the idea of the popular.

Yes, through their demagoguery.

It seems to me that the popular and the serious are brought together beautifully in your theme this year of ‘bittersweet Vienna’.

That’s true, and of course the distinction is shown up by Nali Gruber’s music [HK Gruber is known as Nali], which is not afraid to embrace Kurt Weill. As it so happens, I began my ten years as Intendant at Bregenz with a programme featuring Kurt Weill.

Including two rarely done early pieces I believe – The Protagonist and Royal Palace – at the Festspielhaus in 2004?

That’s right. For me, he was absolutely the embodiment of the identity of this festival, which is a combination of the radical and the popular; that’s what Kurt Weill did. It just so happens that we’re ending with Nali who is a great Kurt Weill specialist – he sings and plays and conducts a lot of his music, and he, himself, also embodies that aesthetic, in that he’s not afraid to use jazz and waltz and popular idioms. As a result, he has on the whole been somewhat ostracised by the Viennese establishment, which regards him as a rather eccentric outsider; he’s better known actually in Britain and other places than he is in Austria, so this has been a big event for him, to have this kind of recognition here. But you could hear that last night of course [a performance of Gruber’s opera Gloria – a Pigtale at the Landestheater]. That’s basically a sort of jazz band opera, but written with an astonishing sophistication and delicacy.

Indeed, yes, with incredible detail – what scoring!

Absolutely brilliant, the score is just breathtaking. Tales from the Vienna Woods is an equally sophisticated piece of work. But Nali very much embodies that, and of course that’s something that is meat and drink to this festival. Because the other thing that makes Bregenz almost the opposite of the WNO is that we’re 80% self-financed here. Our subsidy has been frozen since 1997, so it’s now worth well over a million less than it was.

That must present an enormous challenge on lots of levels?

Well, we have much more flexibility than WNO because we have the possibility of generating very large sums of money.

With the lake stage [which has seating for 7,000 people]?

– With the lake stage – and of losing it too! A rained-out Saturday night, which we had last week, costs us 400,000 Euros because the run is sold out; we have no further seats to offer people as chances to come back again. So all the people who don’t have the so-called house tickets, have to be paid back if we’ve performed for less than a hour.

Goodness, that’s living on the edge in more ways than one isn’t it, with the weather?!

Well, we do build that in of course. After two performances we’re insured anyway so the maximum we can lose is 800,000 Euros.

Which still seems a huge amount! Just thinking about ‘bittersweet Vienna’ for a moment, it strikes me that The Magic Flute is a wonderful foil for Nali Gruber’s music, but there’s also something about ‘Flute itself embodying both the bitter and the sweet. That opera is sometimes seen as all sweetness if you like – in romantic terms at least – and it’s not at all; to me there’s a lot of nightmare in it.

Very much so, and you’ll see in this version that, actually, Sarastro is a very sinister character. Sarastro belongs in jail in my book! – and so that darkness is definitely exploited. And of course two people try to commit suicide in The Magic Flute!

Plus the sexual violence and threat thereof!

Yes!

But it’s often the Queen of the Night who is labelled the ‘baddie’ in plot terms – people sometimes don’t get beyond that.

Well, I think all of that just comes about because people treat Sarastro as the ‘goodie’. And actually, the minute you distrust Sarastro the whole piece becomes totally logical because it’s then a piece about the modern figures – the people with the modern music, Pamina and Tamino – being the future, and the process of the piece is to make Sarastro and the Queen irrelevant.

Right, so together Sarastro and the Queen of the Night represent the old order?

Yes, they both die in my Magic Flute. They die in the last minutes, the final battle. And what we always said was, ideally – and that’s why the setting on the lake stage is this primitive island with primitive creatures on it – because that whole world is primitive, with these hierarchical authorities – really what should happen is that the whole set should just sail off and sink into the Bodensee! Because it’s over, it’s finished, and the world belongs to the rational, enlightenment future. If only!

If only, yes, indeed! So is there something here about the questioning of what is ‘natural’ – on many levels, but especially, what is ‘human nature’- within that fairy tale setting? People often talk about the Enlightenment as something that pitched rationalism against instinct, for instance – and I wonder whether that’s another false binary which the opera addresses?

Well in The Magic Flute you have the instinctive person who is another of the people who are going to be part of the future, and that is Papageno. So in a way that is catered for in the piece.

With Papageno it’s interesting that Mozart physically mutes him – what a thing to do to an opera character! – so he can’t speak let alone sing.

Yes! – if only for a short while.

And then one of the tropes in it involves speech. Tamino has to remain silent – whilst Papageno is accused of chattering too much, which is something women are often accused of!

Indeed, and they are accused of it in The Magic Flute. What is it? ‘Ein Weib tut wenig, plaudert viel.’ [‘A woman does little, chatters a lot’. Said by one of Sarastro’s Priests.]

But that whole idea of the battle of the sexes is there as well in the piece – perhaps in terms of the new generation coming in and having to find their own way based not on power, but as equals, based on reason?

Yes perhaps, I don’t know; that is, Mozart and Schikaneder [the librettist] thought of it differently, but it’s interesting how well the piece responds to being looked at in that way. For example, right at the very end of the piece, it’s Pamina who leads Tamino through the trials. Now I’m sure they were not making any kind of feministic statement in those days but it’s just a little example of the way in which the piece has such flexibility that it can take an interpretation that I’m sure Mozart and Schikaneder never had in their minds. Obviously they saw Sarastro as a kind of Freemason, an example of the future, but they littered the piece with enough problems that it remains open. The whole identity of Monostatos for example is… Well, you’ll see – a solution to that is proposed in the first seconds of the production. You’ll need to be awake and watching!

Now that’s intriguing – and I can’t wait to see it [you can find my review here]. I can see the three ‘Drachenhunden’ of the set now out of your window – the ‘Dragondogs’. What are they in your production – are they guardians of the island, or keepers of the Masonic fire in some sense?

There isn’t any Masonic reference in this production really. Yes, they’re guardians of a primitive world I suppose. And of course they fulfill a very important – not really practical but necessary – function in terms of defining proportion. Because you have no proportion out there on the lake stage, there’s no frame. When you’re sitting there as part of the audience, you can’t see anything that would give you a sense of size. So one of the things that as a director you have to do on the Seebühne is to define the proportions of the space, which can be different in each piece. And they are very different from one production to another, because you’re not confined within a predetermined foot-print, such as is dictated by a proscenium arch. Some productions spread out with lots of water in between and some concentrate together, and some go upwards.

Has working with the Seebühne changed your thinking as a director, in terms of the ways you might use a more conventional space such as WNO’s at the Wales Millennium Centre?

I don’t think so – you have to think very differently out on the lake. Some of the solutions that we’ve adopted are to do with that, actually. For example, in my view the Three Ladies are not really solvable on the lake stage. Because what you’re trying to do out there all the time is to push people apart; if you have a love duet, you want that love duet to have ten metres between the duettists, and then you get this fantastic, epic tension out there. As soon as you have three people standing around like this (moves cups together) it looks totally boring, but if you do that with the Three Ladies (moves cups apart) then the musical ensemble falls apart. And so that’s why we decided to represent the Three Ladies with puppets, sung from inside, where the orchestra is. You get an ideal musical cohesion but then you can have three fantastical figures on the stage who incorporate an idea which fits the scale out there.

So I presume the puppets can be large.

They’re very large, yes.

Ah, so there are the three large dragondogs and the three ladies… what do you do with the three boys? – It’s full of ‘threes’ actually this opera isn’t it, to the great joy of the Masonic interpreters!

It is! Well the three boys are performed by dancers and are also sung from inside.

Without yet having seen it! – but hearing you speak and looking at the stage – the ‘Flute seems to me a fantastic opera to stage here. There’s a phrase I believe you’ve used for the lake stage productions: ‘intelligent spectacle’.

Yes that’s my phrase.

I think Mozart would have loved that!

I’m sure he would!

As we’ve touched on, The Magic Flute is full of all kinds of different ideas related to the Enlightenment. I’m intrigued by how Tales from the Vienna Woods might echo that in a sense, albeit in a very different way. Horváth’s play [of the same title], which Gruber has used for his libretto, is full of bitter irony and detachment and estrangement – he takes the idea of reason and shows what happens when reason is perverted and people go passive; when people don’t take responsibility for their actions or thoughts. How does that come into your ‘bittersweet’ theme?

Well obviously Horváth’s title Tales from the Vienna Woods comes from the title of a Strauss waltz. So he is suggesting that the play might be some delightful operetta-ish Viennese confection when it’s the absolute opposite of that in fact, and is really a very bitter piece. The play is also punctuated by scraps of music all the time – the poor girl playing that exact waltz on the piano off-stage! And actually Horváth wrote on the manuscript of one copy of the play, ‘Music by Kurt Weill’. He obviously imagined that that might be possible, which also suggests this bittersweet flavour as it is very much the way one describes Kurt Weill’s music. So yes, they are connected and Magic Flute is also a kind of confection – it has a lot of charm and so on – but as we’ve said, it has these very dark aspects.

The ‘Flute also has a tension between the natural on the one hand and the artificial or mechanical on the other – which I guess might be another Enlightenment theme – with lots of musical and technical effects. There’s a kind of literal acoustic ‘magic’ in the piece, with music onstage and offstage that the characters respond to, the pipes, the glockenspiel/celeste and the flute itself, that are intentionally ‘supernatural’ rather than ‘natural’.

And there are certainly lots of different musical styles which are chosen with a very definite structure. The music for the Queen is basically like Handel really, and the music for Sarastro is going back into a sacred tradition. So those two characters have archaic music – we’re being told they’re out of date already. Whereas Pamina and Tamino’s arias are exceptionally modern, even for Mozart – because they both have a kind of ‘stream of consciousness’ aria in fact, which puts them on a different plane. Then you’ve got the street music with Papageno – his whole aspect – so there are very clear musical signals as to how to read the story.

In terms of that ‘incidental’ music Horváth wrote into his play, I’ll be fascinated to see what Nali Gruber does with it – if indeed he follows the play to that extent – because the music Horváth requests is very specific. Particular waltzes and so on.

Actually, Nali follows the play very closely. It’s really a sort of dialogue piece basically.

It seems to me that in the UK, Bertolt Brecht, who in some ways might be comparable in terms of artistic and political temperament and dramatic skill, has been far better known than Horváth. Is that still true do you think?

Yes I think that is true. The National Theatre have staged Tales from the Vienna Woods [in 1997 and, in a new version, in 2003]. I guess it’s the only play that’s really known of Horváth’s, whereas obviously with Brecht there are many more. Of course, Horváth’s output includes Figaro gets a Divorce – which is going to turn up at some point… [the play transports characters from Mozart’s opera into a chaotic modern situation.]

Ah – that IS intriguing… and are there any plans to bring Nali’s opera to the UK at the moment?

Not as far as I know. I would love to bring it to WNO but I don’t know how we would manage that.

Well I sincerely hope you can! [You can find my review here]. Within Austria, what’s the relationship like between the Festival and Vienna? You’re very distant here from the capital.

Very distant. There hasn’t really been any significant relationship with Vienna other than the fact that we borrow their orchestra [the Wiener Symphoniker, which also performs a series of concerts each year at Bregenz].

Obviously WNO is a national opera company. Are there specific differences in the way opera is viewed in Austria as opposed to Wales or the UK?

Well, the politicians turn up on the opening day; every festival opening the President of Austria is here. This year the Prime Minister came too and a couple of other members of the Cabinet were present. And that’s regarded as normal. Whereas in Wales, although I’m sure various members of the Assembly do come from time to time, there isn’t a sense of them, or of the First Minister automatically coming to the first night of a season at WNO. Obviously a festival is a bit different for the reasons that we’ve discussed, but then of course the whole entourage goes on from here to Salzburg Festival a week later, so you do get the sense that it’s considered much more a central part of Austrian culture. Although equally, as I said, we’ve had a frozen subsidy for a long time – since ’97.

Yes, that’s horrendous.

That’s got to come to an end now, it’s got to be changed. But the festival has managed to do quite well nonetheless – which of course doesn’t encourage them to give us more money!

That’s ironic isn’t it? But ‘bittersweet Vienna’ is at least an Austrian theme from their point of view…

Yes – most of my other themes have not been Austrian. We’ve done Kurt Weill as I say and we’ve done Nielsen.

Maskarade, right?

Yes. We’ve also done Szymanowski, we’ve done Weinberg obviously, we’ve done André Tchaikowsky, Judith Weir, Detlev Glanert – who’s German – but this 2014 Festival is actually very Austrian because we’re doing Nali, then also the ‘sitcom opera’ tonight [Life at the Edge of the Milky Way, touched on briefly here, penultimate section] is by Bernhard Gander, who’s a young Austrian composer. And obviously The Magic Flute is very Austrian.

Also, the other music-theatre piece which is being premièred, Trans-Maghreb, has an Austrian composer [Peter Herbert] and librettist [Hand Platzgumer, with Ingrid Bertel]. It’s turned out logically, as I was doing Nali Gruber, that there would be a certain Austrian emphasis this year, but it’s not something that I’ve felt obliged to do. I suppose I felt that at least one of these three composers that I’ve commissioned this year should be Austrian really – I mean, fair enough!

Am I correct that you’ve given five major world premières here in the last five years?

Yes, in the last five years.

Which is a great record.

We’ve done, I think, twenty-two world premières altogether if you include the smaller-scale pieces!

Which is greater still! Will there be any further correlation with your ‘British Firsts’ series at WNO, having brought over Robert Orledge’s completion of Debussy’s La chute de la maison Usher?

Well I’m hoping that the final one will be a production from here actually… to be confirmed…

Ah, we’ll wait and see! I gather that Nali’s opera was originally planned for 2013 but that he needed more time to complete the score. When programming, do you always have in mind a Plan B in case events force a change?

Actually no, not at all! And originally I wasn’t going to do this extra year here either, but there was a big muddle about the succession, and then they appointed someone who didn’t turn up – or anyway was sent back again before he could even start! – so then I was asked to take care of this extra year. Then the situation with Nali came along – and actually I think André Tchaikowsky really found me; it was quite, quite funny. [Last year saw the posthumous première at Bregenz of Polish composer André Tchaikowsky’s The Merchant of Venice, directed by Keith Warner. Which, incidentally, was awarded ‘Best World Première’ at the 2014 International Opera Awards. Tchaikowsky lived from 1935-1982. He died in Oxford, and was no relation to the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky].

So how did the Tchaikowsky opera come about at Bregenz?

Well, I’d done the Weinberg portrait in Leeds and a Russian musicologist called Anastasia Belina-Johnson came up to me and said, oh you’ve done Weinberg, now you have to do André Tchaikowsky, and I sort of went, ‘What?!’ It rang a bell because in fact he had played through a part of The Merchant of Venice to a group of us at English National Opera – in 1982 I think, in the first year I went there. We hadn’t done it for one reason or another, and very shortly after that, Tchaikowsky sadly died and the opera had fallen out of my mind really.

Anyway, so this woman mentioned it to me on this particular day in Leeds, and the very next day I flew to Warsaw. There I was, in the foyer of the Grand Theatre in Warsaw, and from the far corner of this huge marble foyer, a little figure came out and came up to me from across the whole foyer and said [in a heavy Polish accent] ‘Ah Mr Pountney, oh yes, now you’ve done this Weinberg you know the next thing you have to do is André Tchaikowsky’. So I went [looking up] ‘ok ok, I get the message’! I thought, well I have to do something! I got the piece and we had some play-throughs down in Wales and I thought yes, ok. So when Nali came up with a revised timing I knew exactly what to do! But it was chance. André Tchaikowsky’s dybbuk!

And when you return to Wales – very soon – you will be thrown immediately into rehearsal for new productions of two Rossini operas!

Yes! To me this is actually a marvellous opportunity to encounter a great composer who had entertained the world with countless masterpieces. Then, right at the end of his composing career, he engaged historically for the first time with a real political subject in William Tell. Because we live in a time which is dominated, really, by the disasters caused by people’s aspirations to freedom, it’s very interesting to see this topic being discussed in the first real political opera since Fidelio.

Rossini has so often been unfavourably compared to Beethoven as a ‘lightweight’ but actually to ignore or discount William Tell – and indeed even the far earlier Moses in Egypt – as serious opera is a huge mistake.

Yes. Moses in Egypt actually starts out sounding like Beethoven – it starts out sounding like something out of the Missa Solemnis!

Doesn’t it! Well I look forward to the season. In the meanwhile, to Mozart and Gruber! Many thanks for speaking with me.

David Pountney’s production of The Magic Flute at Bregenz is available on DVD (Unitel Classica). His production of William Tell opens at the Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff on Friday September 12. Moses in Egypt opens there on Friday October 3.

From 2015, Elizabeth Sobotka takes over as Bregenz Festival Intendant, the first woman to hold the post. She has been director of Graz Opera since 2009.

A revival of Dominic Cooke’s surreal staging of The Magic Flute has been programmed by Welsh National Opera for Spring-Summer 2015. For those – like me – who have yet to see it, WNO promises that it will be ‘warm and witty’, ‘irrepressibly entertaining’, and ‘featuring an angry lobster, a newspaper-reading lion and a fish that is also a bicycle’.

And why ever not?

original illustration by Dean Lewis

With thanks to Wales Arts International for their generous support.