Opera masterclasses are an integral part of the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World programme. They provide invaluable advice to the young conservatory students who participate, and inform audiences about the unique demands made upon singers in performance. Phil Morris attended a directing masterclass delivered by David Pountney, Chair of the Cardiff Singer Jury and Artistic Director and Chief Executive of Welsh National Opera.

Dora Stoutzker Hall, Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, 19 June 2015

To those unfamiliar with the workings of the rehearsal room, it is tempting to think of the opera director as someone responsible simply for mounting a spectacle to match the sublimity of the music. Discussions of a director’s ‘take’ on a famous opera often centre on a concept – The Magic Flute transposed to the subterranean sewers of Vienna with strong Freudian overtones, that sort of thing. David Pountney’s many triumphs at WNO have been distinguished by compelling conceptual framing and bold visual designs, however the spectacle has always been underpinned by his psychologically insightful approach to character, and his intense focus on opera as human drama as rather than mere staged singing.

The opening scene of Don Giovanni was therefore an appropriate choice for his masterclass. The Mozart-Da Ponte masterpiece is a cautionary fable on the perils of hubristic hedonism exemplified by its eponymous anti-hero. Yet the enduring fascination of Don Giovanni lies not so much in its moral lesson but in its detailed and psychologically nuanced examination of relationships. The opera features a set of young lovers caught up in a narrative web of sexual desire, guilt, recrimination and power. Both libretto and score portray these complex and dynamic relationships in a richly layered text that requires exhaustively detailed analysis.

Pountney begins by explaining to his audience that before putting the scene on his feet, he and his performers ‘would normally spend an hour talking’ about their characters and what happens to them during the scene in question. Chanae Curtis (Donna Anna) and Andrew Henley (Don Ottavio) quickly agree that they are to play a pair of sheltered, young aristocrats who have blithely entered into betrothal having once been childhood sweethearts. The chaste innocence of this relationship is to be shattered in the opening minutes of Don Giovanni by the title character’s attempted rape of Donna Anna and his subsequent murder of her father, the Commendatore. Pountney summarises their brief discussion by underlining that these, ‘[A]re two confused young people dealing with monstrous events’.

The scene takes on a distinct shape as Pountney frequently draws the attention of his performers to the clues, or indications, embedded within the score and libretto; so that the confusions and welter of complex emotions experienced by each character are delineated with clarity and empathy. Pountney is particularly insightful on Donna Anna’s impressionistic post-traumatic recollection of her near rape. He directs Chanae Curtis to physically recoil from Don Ottavio’s touch as he tries to console her, reminding her that only moments before the opera has begun Donna Anna’s body has been subject to a terrifying violation. Andrew Henley’s buttoned-up Don Ottavio is similarly brought to life as he is asked to consider the inescapable futility of his character’s response to Donna Anna’s outrage and grief.

Pountney constantly attempts to inspire his performers to achieve the illusion of spontaneity, which, when successful, makes the scene increasingly compelling even when the action is repeated over and again as part of the rehearsal process. He frequently reminds his performers, ‘You don’t know these words. You haven’t spoken them before in your life’. In other words, the performer’s awareness of the musical line they have to sing should not result in their performance seeming calculated or wholly preconceived. At several points the aim of realising emotional truth in performance appears even to supersede musical imperatives. Pountney highlights several moments at which an understandable instinct to sing well must be curbed to better communicate the emotional truth of the character’s experience. He advises both performers, ‘Try not to be too artistic. You don’t have to make it beautiful’.

The effort of one hour is expended on the staging of what would constitute only a couple minutes of stage time. What begins to emerge from these pain-staking efforts is – in spite of the centuries old Italian words and classical music – an intensely powerful and convincing portrayal of a young couple dealing with the psychological fallout of a brutal sex attack and murder. Watching the scene take shape we are reminded that opera is not an archaic art-form that only reifies the past, it is a mode of human drama in which our most primal, dark, deep and transcendent experiences are expressed. Mozart is our contemporary when his music is sung as if for the first time, by characters who are only conscious of what they are about to say at the very moment their feelings are vocalised.

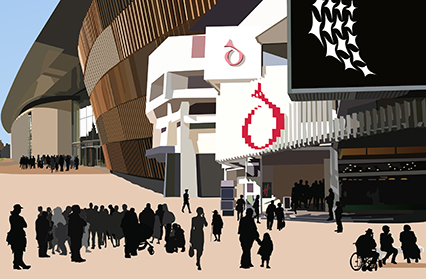

Illustrations by Dean Lewis