‘We deny the right of any portion of the species to decide for another what is and what is not their “proper sphere.” The proper sphere for all human beings is the largest and highest which they are able to attain to.’

– Harriet Taylor Mill

The notion of female enfranchisement, and more latterly gender equality, is a relatively new concept in political and cultural discourse. For millennia a woman’s role and place in society has, more often than not, been defined by her relationship to men – as a wife, mother or daughter, but never as an equal, that is independent or free. Even great female historic figures, such as Elizabeth I (The Virgin Queen) or Cleopatra, are significantly defined through their relationships, or lack thereof, with men. Through religious dogma and cultural norms, the role of women in society has not developed for much of our history, it is certainly true that women have mostly fulfilled the role of domestic slave; destined from birth to undertake a position in society that was always subservient to man. From Genesis 3:16 assertion that ‘Unto the woman He said, “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception. In sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee”’ to considerably more modern forms of discrimination (witness the current conversations concerning the limits of women in politics, music and comedy), the insistence that this is a man’s world is undoubtedly true.

However, it was during the age of revolutions (the French, American and Industrial) that the seeds of possibly one of the most significant cultural advancements were planted. The publication, in 1792, of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman began the slow process of debate and dispute that challenged a contemporary society that cherished tradition and innate cultural conservatism over equality and reason. The arguments that Wollstonecraft outlines, that men are not naturally superior to women and lack of education is the only difference between the genders, were easily dismissed by a patriarchal society. But as the new century developed the arguments grew in volume: Jane Austen and the Brontë family started to describe polite society from an often unheard female perspective; women began to enter the industrial workforce; and institutional education reform was also introduced. Throughout the massive upheaval of the nineteenth century the fight for political representation was constantly being waged, the horrendous inequality between rich and poor was only heightened by the newly established industries and forms of commerce. The clamour for parliamentary representation from many sections of society became deafening.

The first significant attempt at forming a national organisation to lobby for the enfranchisement of women was started in 1867. Lydia Becker, founder of National Society for Women’s Suffrage, developed many of Mary Wollstonecraft’s assertions on education and gender equality and won a surprising victory for women’s suffrage in the Isle of Man, by securing the right to vote for women in the 1881 election to the House of Keys. However, this small victory had little impact on the plight of women’s suffrage on the mainland of Britain. Despite the support of many radical Liberal MPs, such as John Stuart Mill, the momentum of the suffrage movement was beginning to stall. The lack of any progression in the suffrage cause forced a split, in 1903, in the ranks of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) – a small minority, including Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, believed that the constitutional approach to claiming the vote for women, undertaken by NUWSS, was too passive and ultimately ineffective. The formation of Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a bold and militant step in claiming victory for female enfranchisement. By 1913, WSPU had come to dominate polite conversation and newspaper headlines in the stifling orthodoxy of Edwardian Britain.

The upbringing of Hannah Mitchell was a fairly typical existence for a woman in the Victorian era. Born in 1872, Mitchell was denied a formal education by her parents and expected to assist her mother in supporting the male members of her family – disillusioned with the prospect of eternal domestic slavery and marital servitude, she ran away from home at the age of fourteen to Bolton in search of employment. After witnessing her mother driven to furious outbursts of anger and despair by the monotonous drudgery of housework, Mitchell quickly became radicalised by first socialism and then the Suffrage Movement. However, unlike many of her WSPU colleagues, including the Pankhursts and Margaret Haig Mackworth who were born into relatively comfortable economic surroundings, Mitchell knew only too well the struggles and indignity of being poor and female. In her autobiography, The Hard Way Up, Mitchell honestly details many aspects of an average woman’s life that led her to believe that militant suffrage was the most efficient way to secure the vote. From the ‘sheer barbarism’ of child birth to the subjugation of marriage, she became vehemently resentful of the inequality of the sexes, and embittered at the freedom and opportunities afforded to men. She noted:

Perhaps if I had really understood myself, as I did later, I should not have married. I soon realised that married life, as men understand it, calls for a degree of self-abnegation on the part of women which is impossible for me. I needed solitude, time for study and the opportunity for a wider life.

It was not just the traditional role of women that drew so many to the militancy of the WSPU. Working conditions and employment opportunities for women in the pre-war Britain were limited at best and non-existent at worst. Annie Kenney, one of the most indefatigable members of the WSPU, had started work at a local cotton mill at the age of ten years-old to help her parents (and eleven siblings) survive the crushing economic reality of so many of Britain’s working poor. For many working class women there were limited employment opportunities available in the mills, mines and in domestic service, but little chance of any progression from general hard labourer. However, for the women of the established lower middle classes the options were fewer; teacher, Poor Law Guardian, wife and mother. The glass ceiling was so restrictive, in terms of employment, that it would have been more accurately described as a glass cage. The suffocatingly limited employment opportunities combined with the lower wages for women, for instance Kenney would have been paid up to fifty percent less than a man who did a similar job, meant that many women felt the constitutional approach of the NUWSS, although valid, would not produce the required results. Sadly the correspondents of a man in Twickenham to his local newspaper typified the indignation felt by many people towards the Suffrage Movement:

It is a pity that women, especially married women, cannot find sufficient domestic duties to keep them from such acts as these, and helping to lower the opinion of the British woman in the eyes of other nations.

Dr Martin Luther King once pronounced ‘a riot is the language of the unheard’, and whilst the Suffragettes never rioted, the actions undertaken by the WSPU were these women shouting to be understood. Political and civic institutions were failing women – employers exploited them, husbands could beat them and a society ignored them – yet it was only men that had proper recourse against the vagaries of a conservative society. Emmeline Pankhurst identified that women suffered in society because their experiences and opinions were never understood in Parliament (a Parliament run by men, voted for by men and which produced laws designed for men). If the lawmakers do not understand the issues faced by a section of people, how can they produce a law to help them? It was clear, to the WSPU at least, to attain an equitable Britain, for both sexes, that women must be free to vote. Emmeline Pankhurst noted that

It is perfectly evident to any logical mind that when you have got the vote, by the proper use of the vote in sufficient numbers, by combination, you can get out of any legislature whatever you want, or, if you cannot get it, you can send them about their business and choose other people who will be more attentive to your demands.

However, Parliament was reluctant to change. It was through both ideological stubbornness and political pragmatism, that the Women’s Franchise Bill and the Conciliation Bills did not pass the reading stages. Even though many Liberals in the government supported the idea of women’s suffrage they still voted against these Bills because they believed that it would gift the Conservative Party one million more votes – considering that the Liberal Party lost the popular vote in the December 1910 general election by over one hundred thousand votes, they still controlling majority in Parliament (thanks to our wonderful first-past-the-post voting system) – it was a risk that the Prime Minister HH Asquith was unwilling to take. This failure of Parliament was the final insult to the Suffragettes and, as the prospect of a global conflict darkened the horizon, the WSPU stepped up their campaign.

The images of Emily Wilding Davison being struck by the horse of King George V, Anmer at the Epsom Derby, whilst she attempted to grab the bridle in 1913, is still as shocking and poignant today as it has ever been. This desperate act of rebellion is in itself worthy of commemoration, the ultimate sacrifice given for what today we take as a mundane democratic right. However, there were many more women, in 1913, which yielded their rights, health and freedoms in order to secure a better, more equitable, future. Many Suffragettes, including Kenney, Pankhurst and Haig Mackworth, were imprisoned in 1913, as the WSPU undertook a campaign of window smashing, arson, pillar box burning, bombing public buildings and more general acts of civil disobedience. Under the green, white and purple banner that proclaimed ‘Deeds Not Words’, the Home Office, Kew Gardens, David Lloyd George’s house in Walton-on-the-Hill and the Tower of London all became legitimate targets for the Suffragettes’ anger. The justification for this increase in militancy was made by Emmeline’s daughter, Christabel Pankhurst, while in Paris avoiding prosecution in Britain, she opined ‘[t]he fact that the miners are going to get legislation because they have made themselves a nuisance is a direct incitement to women to endeavour to obtain a similar privilege’.

It is noticeable that none of these attacks against property, firstly public but latterly private, were intended to physically harm any person, instead they were a clear message to Parliament that voting rights for women was a non-negotiable demand. The obvious consequence of these defiant acts was the incarceration of many leading members of the WSPU in some of the worst jails in Britain. The suffragette leadership, including the Pankhursts, knew the publicity value of women being imprisoned for their campaign was significant; to highlight this even further, and to protest at the truly appalling conditions that inmates were subjected to, many suffragettes began a hunger strike. Though technically not illegal, the government realised the public relations disaster if it allowed any one of the suffragettes to die in prison while on hunger strike – so it initiated a policy of force feeding to ensure that the prisoners were healthy enough to serve their sentences. However, the forcible feeding of women in prison became the perfect metaphor for the suffrage movement; women, keep against their will, subjugated by men and who had no control over their own destiny, not even death.

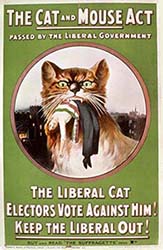

The Liberal Government’s response to this escalation in hunger striking was the introduction of the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 or more commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act. It was believed that by letting the suffragettes (the mice) to go on hunger strike and then releasing them on license when they became weak and malnourished, only to re-arrest them once their condition had improved, was preferable to the negative publicity that surrounded the forcible feeding procedure. Also the government thought that there could be a secondary benefit in keeping the suffragettes as weak and frail as possible as the women would less likely to be undertaking any nefarious activities while on license. However, what was designed as a discreet method to deal with the suffragette problem became genuinely counter-productive, as it undermined the government’s moral authority and developed into the embodiment of the movement’s struggle in the public’s consciousness. But as the time passed, it was the untimely death of Emily Davison at Tattenham Corner that will always symbolise the sacrifices made for the suffragette movement and democracy in Britain as a whole. In life she was a nuisance, but in death she became a martyr.

The Liberal Government’s response to this escalation in hunger striking was the introduction of the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 or more commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act. It was believed that by letting the suffragettes (the mice) to go on hunger strike and then releasing them on license when they became weak and malnourished, only to re-arrest them once their condition had improved, was preferable to the negative publicity that surrounded the forcible feeding procedure. Also the government thought that there could be a secondary benefit in keeping the suffragettes as weak and frail as possible as the women would less likely to be undertaking any nefarious activities while on license. However, what was designed as a discreet method to deal with the suffragette problem became genuinely counter-productive, as it undermined the government’s moral authority and developed into the embodiment of the movement’s struggle in the public’s consciousness. But as the time passed, it was the untimely death of Emily Davison at Tattenham Corner that will always symbolise the sacrifices made for the suffragette movement and democracy in Britain as a whole. In life she was a nuisance, but in death she became a martyr.

So, why is it so important to commemorate this hundredth anniversary? Is it just to pay tribute to the sacrifices made by Emily Davison and her colleagues in making our society more equitable and democratic? There, of course, should be a significant element of remembrance in this commemoration, but it also gives us a chance to put in perspective the challenges that still face us. The women fighting for the vote a hundred years ago, weren’t fighting for an abstract notion of civic involvement or democratic idealism – they saw the vote as an instrument to improve the lives of all women in Britain; who, for too long, had been ignored and abused by a deeply conservative and patriarchal society. Many issues that blighted the lives of women in Edwardian and Victorian Britain are still in existence today; the glass ceiling and limited employment opportunities, the projection of a stereotypical role of women in society, pay inequality and the representation of women in our civic institutions. Although there has been significant improvement in many of these areas, there is compelling evidence that suggests that we still have a long road to travel to reach a truly equitable society. Currently women earn on average fifteen percent less than their male counterparts. In Parliament women make up less than a quarter of all MPs. The justice system is only now beginning to realise that attacks against women, including rape, are not brought upon themselves. There is a complete lack of female representation in the boardroom of Britain’s companies, one survey suggesting less than one fifth of all boardroom members is a woman. The victories of the suffrage movement were hard won, but there are many battles ahead if we are going to ensure a fair society for everyone, regardless of gender, race or economic heritage.

Illustration by Dean Lewis