In the first of a new series, John Idris Jones unearths the treasure trove of literature from Denbigh’s rich past.

The ancient town of Denbigh lies on the western edge of the Vale of Clwyd, headed by the remains of a stone castle, facing the rich acres of the vale. It is to the west of Chester, some twenty miles distant; the two are connected by the A543, which comes in to the Vale through a low-lying road through a gap in the Clwydian Hills. Farther south, along the lines of these hills, there is no such access, and the location of Denbigh has its origins in its low-lying road access, between Bodfari and Caerwys, to the English border and the cities of Chester, Shrewsbury and London.

Another major factor in its origins and significance is the high value of land that surrounds it. A number of ambitious families settled here, from the thirteenth century to the nineteenth; they built comfortable houses and acquired land, which was well cultivated by tenant farmers. Foremost among these was the Salusburys: Sir John Salusbury was a revenue-collector for Henry V111 and in the mid-sixteenth century he built the three-winged mansion Lleweni, which was significantly visible to visitors who arrived through the Bodfari gap.

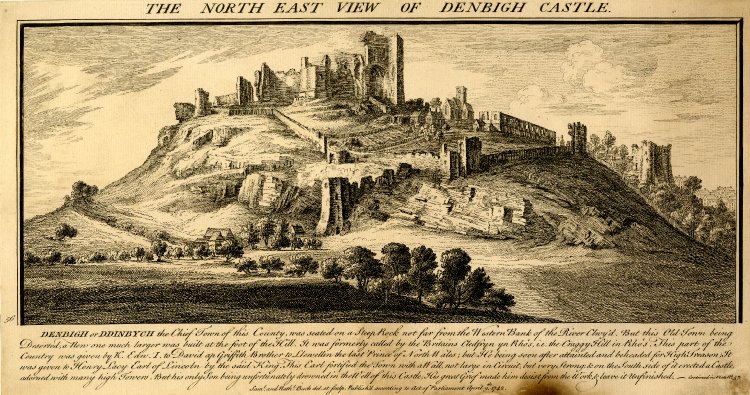

Denbigh was located within a Marcher Lordship. The area is the most northern part of this borderland territory which was in the gift of the sovereign: indicating this is the deGrey family who owned Ruthin’s castle and assets in Ludlow. Denbigh’s first charter was granted in 1290: its castle was fought-over by Welsh and English armies and was overtaken by Edward 1. Owain Glyndwr’s insurrection in the first years of the fifteenth century had it burned and occupied. The Wars of the Roses (1455-1487) saw Denbigh repeatedly attacked and in 1643 the Royalists used the castle as a refuge during the English Civil War: not much is left of it now.

This background indicates a settlement which gathered sophistication over the centuries. Road contacts with the English cities increased; businesses flourished; lawyer/accountants offices took their place; banks opened, agricultural traders became a necessity: all these and more became part of the socio-economic mix. Consequently, writing and writers proliferated. In the early centuries, education was confined to private tuition for the wealthy, who sent their sons to Oxford and Cambridge at a very early age: Jesus College, Oxford and Trinity College Cambridge were favourites.

An unusual number of writers in English and Welsh emerged; some were born in Denbigh and its environs, others came to the area and stayed for a significant amount of time.

John Salusbury (1567-1612)

Salusbury was the second son of Catrin of Berain (Henry V11s great-grand-daughter and a cousin of Elizabeth 1st). His brother Thomas was put to death in 1586 for his part in the Babington Plot. His grandfather, the very wealthy Sir John Salusbury spent time in the London parliament and court; his effigy, with his wife, are depicted on a prominent tomb, along with their children, in St.Marcella’s Church, Whitchurch, Denbigh.

This John (the third in succession) was educated at Jesus College, Oxford, completing at the age of fourteen. He studied law at the Middle Temple from March 1595 and Elizabeth 1st appointed him ‘squire of the body’, so he was a figure at her court. He married Ursula, a daughter of Henry 1V, Earl of Derby, (West Derby, Merseyside) in 1586 and was a frequent guest at the wealthy Earl’s fine houses in Lancashire. Henry and his son Ferdinando ran touring theatre companies and it is likely that John Salusbury was acquainted with theatre people in London in the 1590s. In his book ‘Eminent Men of Denbighshire’ H. Ellis Hughes describes John Salusbury as “..a friend of Shakespeare’s.” In her book ‘Ungentle Shakespeare’ Prof Katherine Duncan-Jones writes: “From the Earl of Southampton to Sir John Salusbury to ‘Mr W.H.’ to Frances Manners, Earl of Rutland, Shakespeare’s visible patrons were all male.” John Salusbury was knighted by Elizaeth 1st in 1601 for his support during the Essex Rebellion.

John Salusbury’s verse writings are available to us in the volume ‘Poems by Sir John Salusbury and Robert Chester’ first published as a Bryn Mawr College Monograph, edited by Carleton Brown, in 1913.Writings by John Salusbury are also in handwriting in the Salusbury commonplace volume MS 184, held in Christ Church, Oxford. The other selection is in a very rare printed volume with the text on the title-page beginning “SINETES Passions upon his fortunes, offered for an Incense at the shrine of the Ladies which guided his distempered thoughts…by Robert Parry Gent at London..1597”. This little book was put together by Parry, a resident of Denbigh, to display his friend’s ability in poetry, and to please him, as an influential neighbour.

At least thirty poems were penned by John Salusbury and appear in these two collections. He was fond of sonnets and initial capital letters forming acrostics are used forming the names of two of his lovers – Dorothy Halsall and Blanche Wynn. Other longer poems, usually of love and devotion are in six-line stanzas.

Hugh Holland (1569-1633)

Shakespeare’s ‘First Folio’ of 1623 is one of the most valuable books ever published in the English Language. It was edited by Shakespeare’s friends and fellow-actors, John Heminge and Henry Condell and is the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays. The preliminary matter includes, occupying page eleven, a praise-poem above the name HVGH HOLLAND. The head text reads: Vpon the Lines and Life of the Famous Scenick Poet, Master WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE. The following sonnet begins: “Hold hands, which you go clap, go now, and wring/ You Britain’s brave; for done are Shakespeare’s days/ His days are done, that made the dainty Playes/ Which made the Globe of heaven and earth to ring/ Dry is that vein…turn all to tears…”

It is not great poetry. The interesting thing is that it is there, beside a praise-poem by Ben Jonson, one of Shakespeare’s closest friends and rival in writing plays. The publishers/printers must have had a good reason for selecting him as the writer of commendatory verse for their prestigious volume. He was a prominent man of letters.

Hugh Holland was born in Denbigh, the son of Robert Holland. He was educated at Westminster School under William Camden. He was a classics scholar and obtained a scholarship at Trinity College, Cambridge: subsequently he travelled in Europe and lived for months in Rome. He published a poetry collection ‘Pancharis’ in 1603 and another collection ‘ A Cypres Garland’ in 1625. He was buried in Westminster Abbey on 28 July 1633.

Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) and Hester Thrayle (1741-1821)

Hester Thrayle was the last of the Salusburys; a direct descendant of Catrin of Berain. She married Henry Thrale, a rich brewer, in 1763. They had twelve children and lived at Streatham Park, London. They befriended Dr Samuel Johnson and gave him lodgings under their roof for many years. Her husband’s status enabled Hester to engage in society and she was friendly with many literary and political figures of her time. She was interested in the biographies and homes of her Welsh ancestors and in July 1774 she toured North Wales with Johnson, spending time in the Denbigh area. On the 28th July, “We entered Wales, dined at Mold, and came to Lleweni” is Johnson’s pithy comment. (Lleweni, the home of the Salusbury family, was then a three-winged mansion set in rich parkland about a mile outside Denbigh: it still exists, but is now smaller).

“We came to Lleweni, which struck me extremely as an old family seat of no small dignity,” writes Hester. “..superflous space seems to be one source of satisfaction in the house, and here is a hall and gallery which never seemed intended for use, but merely stateliness of appearance. The gallery is exactly seventy five of my steps to the end..” She and Dr Johnson stayed in Lleweni for three weeks, visiting friends and places of interest. Hester’s mother had lived in LLeweni and Hester spent time there in her younger years. In 1774 Lleweni had a fine library and, according to Meurig Owen, “..works of art adorned its galleries and staircases. In common with other great houses of the period there would be a welcome for itinerant harpists and bards. Indeed many were themselves literary people.”

A visit to nearby Bachegraig brought Hester the comment that the River Clwyd, “rolls at the foot of the meadow in front of the house. There is a bridge by Inigo Jones of a single arch that faces the door..” Sam Johnson retorted, “The River Clwyd is a brook with a bridge of one arch in about one third of a mile.” The house, which was built by Hester’s ancestor Richard Clough in the late sixteenth century, was in a state of neglect.

On August 1st 1774 Dr Johnson and Hester Thrayle walked the streets of Denbigh. Johnson notes the boys playing by the castle walls. “Each view is called the most beautiful till another is examined,” Hester writes. “It looks like a ruin built on purpose in the midst of a delightful garden belonging to a man of exquisite taste.” The party then went on to “..the parish church of Denbigh which being near a mile from the town is only used when the Parish Officers are chosen. This was Whitchurch, St. Marcellas, so called because the Carmelites wore white. Here Dr Johnson noted the commemoration plaque to Humphrey Llwyd (1527-68), the cartographer who was the first to design and publish a map of Wales. Another Denbigh notable is remembered by a brass celebrating the life of Sir Richard Myddelton (1508-75) whose two sons Thomas and Hugh became famous in London. Hugh was a banker, goldsmith and engineer. He designed and oversaw the building of the ‘new river’ which flowed south to the city for thirty-eight miles, bringing, for the first time, fresh water to the city. It was opened in 1613 when his brother, Sir Thomas, was Lord Mayor of London. Sir Thomas, with another, bore the expense of publishing the 1630 Bible. Both were Members of Parliament, Hugh representing Denbigh borough for twenty-five years and Sir Thomas representing Merionethshire and afterwards London.

The party went to Gwaenynog on Friday 5th August. Sam commented on the “roughly cut” stone of the house, that it had good furniture but that the fruit was bad over dinner. “The dinner talk was of preserving the Welsh language. Myddelton is the only man who in Wales has talked to me of literature..” Hester commented that Myddelton had said that he had never had a great man under his roof and was aware of the honour. This is indicated by a commemorative urn placed in the grounds of Gwaenynog by Colonel John Myddelton. Johnson saw this design and commented, “Mr Myddelton’s erection of an urn looks like an intention to bury me alive.”

During August 6th to 17th Dr Johnson and Hester stayed at Lleweni; she was much concerned about what to do with Bachegraig, her inheritance. They left the Denbigh area on 18th of August.

After Johnson’s death, Hester Thrayle published ‘Anecdotes of the late Samuel Johnson’ (1786) and her letters in 1788. Her diaries were not published until 1949. Her writings come under the name ‘Thraylania’ and are considered to be a valuable account of life in the late eighteenth century, and an honest account of Dr Johnson’s full literary life.