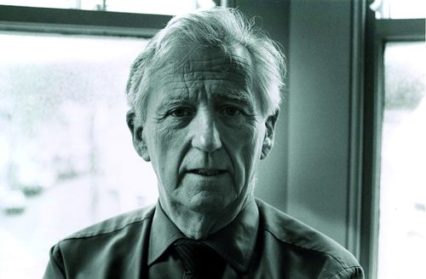

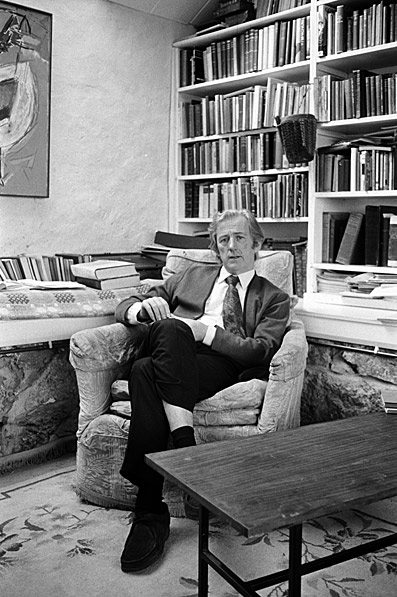

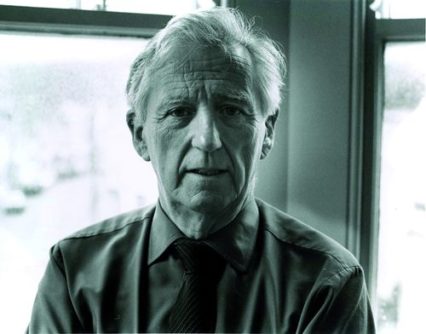

With the news of the passing of one of Wales’s most important writers, Emyr Humphreys, Wales Arts Review republishes this longform tribute from award-winning novelist Tristan Hughes, originally published to mark Humphreys’s 100th birthday last year.

When I was first invited to contribute a piece on Emyr Humphreys, I must admit I was initially filled with a rather profound sense of inadequacy. It is a dauntingly vast subject. And it was only when it was made clear that what was being looked for was a discussion of how his work had influenced my own writing and writing life that I could begin to contemplate it. What we are celebrating this year of his 100th birthday is a mountain range, and I can only shed the smallest of lights on one little corner of that written country; an upland meadow perhaps, a crag or two, a small stream at the base of Moel Siabod.

But I think it is necessary to begin with a glimpse of the wider view: to acknowledge the scope and magnitude of Humphreys’s literary career. In terms of sheer range and ambition and single-minded dedication, there isn’t anything comparable to it in modern Welsh writing. As a writer, it seems to me nothing less than astonishing. Looking at a bibliography of his publications makes my jaw drop. I can barely begin to comprehend the resources it has taken in terms of imagination, knowledge, conviction, talent, and pure stamina to produce such a corpus of work, and one of such sustained excellence. He has chronicled over a hundred years of Welsh life, part of which – the septet of novels that makes up The Land of the Living– is a kind of prose epic of the last century. He has written – and maybe this is as good an example of his range as any – one of the best literary evocations of childhood and adolescence we have in A Toy Epic, while also writing one of the finest depictions of old age in Outside the House of Baal (which also doubles, to my mind, as the finest Welsh novel of the 20th century – or this century too, for that matter).

And just to round out the ages, why not mention that little gem of middle age and mid-life crisis, the novel Jones. He has also written one of the classics of Welsh cultural history, The Taliesin Tradition. And all this isn’t even to mention his short fiction, or his poetry, or his essays, or his pioneering work in television and radio and theatre. It represents a colossal achievement, one comparable to any of the greatest careers in any national literature. And yet even now I sometimes feel it hasn’t always been fully recognised; as ever, the two Thomases still tend to overshadow our perceptions of Welsh writing in English. It is a constant surprise to me that a delegation from a certain committee from Stockholm has not come calling to Llanfair PG. And to think he has been a contemporary of three or more generations of Welsh writers and is a direct link to the golden ages of 20th century Welsh writing in both languages. We are incredibly lucky to have a truly great writer still with us.

And now to admit that I only came to his work late in my twenties and at the beginning of my own writing life. It remains bewildering to me that I didn’t study him at school. How sadly reflective of the Wales of that time – to have a writer of such stature living two miles away from my schoolroom and not one of his books in front of me on my desk. And how even more sadly typical that that very writer had offered one of the most cogent analyses and diagnoses of the cultural and political conditions that enabled such an absence. As Humphreys put it himself, ‘The mind of the serf is haunted by a God whose temple is in a distant city. The habits of centuries die hard.’

*

Influence is a funny old term in literary history: sometimes Freudian struggle, sometimes regicide, sometimes a moody teenager shouting at their parents and storming out of the house. But I think most often it is a simple, or extremely complex, moment of recognition and sense of affinity, and beyond that an intimation of what has been done, and what might be done. It is a door opening, revealing a room with many other doors. As for Humphreys’s influence on me, I can probably group it into three doors, which are essentially one large door – a portcullis, let us call it: place, history, and possibility.

When I first read the famous opening of A Toy Epic it was as though I’d looked out the window and found the landscape framed there was really a Russian doll. As each character introduces himself with his place – Michael’s ‘broad valley’ with the sea curving ‘under the mountains’; Albie’s kitchen parlour in Llanelw; the ‘anchored ark’ of Iorwerth’s farm – what is revealed isn’t just one of the four corners of Wales, but how there are corners within corners. Multiple worlds jostle against each other within the few scant miles that separate Iorwerth’s ninety acres from Albie’s no 15 Cambrian avenue. I can’t say how important this was for me at this stage of my literary life. At that point, I was pretty much like one of the characters I’d often encounter later in Humphreys’s fiction. I’d escaped east in search of what I imagined were broader and more glamorous horizons, and had never thought much of my Welshness, or what it might mean, or that some of those deferred or repressed meanings might be bubbling up inside me. In terms of my vague literary ambitions, I thought literature somehow took place in London or Paris or New York or – if I’d listened to some of my more tweedy professors – at least a hundred years ago (was ever an aspiring writer so naive and ignorant – I am here to say they were).

Some of that had begun to change through my reading of Faulkner. And in a way, I came to Humphreys through Faulkner. I could immediately see the affinities: the stylistic ones in the modernist fragmentation of narrative and charged poetic prose of A Toy Epic, but also in its overlay of landscape and memory and history; in the ways place and time shapes (and warps) individual consciousness and desire and development. Some of my own little adolescent anguishes are there in the various travails of Iorwerth, Albie and Michael, but what I found most clearly revealed in A Toy Epic were the social and physical landscapes, the psychological inscapes, that had shaped my father. He’d experienced directly the often fraught and riven Welsh world of grammar school, town and country, culture, language and class, that that novel so vividly conjures. Of the many flashes of recognition that literature can offer, this illumination of the hidden lives of those who we think we know can be the most powerful. While reading that novel, I began to glimpse something which had been under my nose all along and that I’d barely seen.

In one of my notebooks from that period, there’s a quote from an interview with Faulkner, underlined about eight times: ‘I discovered that my own little postage stamp of native soil was worth writing about and that I would never live long enough to exhaust it.’ That was an important thing for me to read (although the one word that gave me pause then, and has seemed more and more problematic to me since, is ‘native’, and I will come to that later). But, of course, while Faulkner’s postage stamp was obviously a very literary place to me (I’d never been there), Emyr’s north east Wales was in many ways familiar. I had been to Rhyl and Prestatyn. I’d grown up in a rural community much like Iorwerth and Michael’s.

Familiar, but not entirely. Llanelw is, and is not quite, Rhyl and Prestatyn; just as Pendraw is, and is not quite, Criccieth and Pwllheli. Describing this quite-but-not-quiteness in his fiction, Humphreys has said: ‘It’s like a parallel existence. Fiction is a possibility – it could be, but it isn’t. The world of fiction always floats a few feet above the actual ground and enjoys a climate and atmosphere all of its own.’ There is a difference between discovering a literary country like Yoknapatawpha County and seeing a writer turn what is outside your window into one. The latter entails a kind of double recognition: of seeing a place but also the possibility of making a place. The example of Humphreys’s work helped give me the confidence to try and create a literary place – or places – of my own. The freedom offered by those few feet above the actual ground, by the imaginative space of not-quite-ness, was the postage stamp that allowed me to begin writing the letter.

*

Growing up, I often thought my Welsh grandmother lived a mysterious double life. In one, she fed me bread slabbed with heart-attack portions of butter and told me ghost stories and snippets of village scandal and described labyrinthine, and sometimes rather bewildering, genealogies and family histories. Who was my great-uncle Emrys who she claimed had had his hand bitten off by an enraged pig named Bill? How exactly was I related to a man from Texas who turned up to family funerals in a Rolls Royce, wearing an enormous white cowboy hat? Had her cousin Ivor, or was that her uncle, or was that her second cousin once removed, really seen a goat with horns of spinning fire? She was like the living front sheet of a family bible, but much racier, and much funnier. In her other life, she went to help at her chapel at least twice a week, was slightly appalled I had been baptised in a church, and welcomed ministers to come and sit in her kitchen and talk, and talk, and talk … Why did she keep a box of the best biscuits for them? Why, when they visited, did it matter that I’d left my muddy wellies in the hallway? Why was there no mention then of the ghosts and fire-crowned goats and all the other things I loved to hear about? That world I knew only by enigmatic codes of decorum and rituals and relics. I remember playing a triangle in a primary school recital at her chapel (I wasn’t trusted with a recorder) and finding it a strange place that I didn’t know the names and meanings of. What was the ominous sounding set fawr and who sat there? Why was there a big clock on the wall above the gallery, and why did it tick so slowly? It was like a cromlech to me; the spiritual and cultural life it housed impossibly remote and distant. It was a feeling I must have shared with many of my generation. As Wynn Thomas has eloquently described the chapelled landscape of Wales: ‘They are the ruined dolmens of some mysterious, departed civilisation. Like those great stone faces on Easter Island, they still command physical space, but no longer invite comprehension.’

It would take a supreme piece of imaginative retrieval and elegy to unlock some of the secrets of that ‘departed civilisation’ – it would take Outside the House of Baal. Emyr Humphreys has been the great historical novelist of Wales, and of non-conformist Wales especially; and not only in the sense of writing historical fictions, but of a sustained meditation on the endlessly ambiguous presence and meaning of what – in an essay on Kate Roberts – he would call ‘Welsh time’. Outside the House of Baal is full of clocks – some ticking, some not; one the legacy of a dead and half-forgotten friend. Welsh time is a complicated and multidimensional business in Humphreys’s work: part spectre at the feast, part hope of the resurrection; part corpse, part lodestone.

Humphreys has said that the novel was inspired by a moment during a car journey with his mother: ‘Satellites were already in orbit when my mother assured me as we drove at night from Penarth to Prestatyn that it was a bad omen to see the moon through glass, even of a windscreen.’ He began to see how the stories of his mother and father-in-law offered ‘… a vivid evocation of a lost world and of a period of unparalleled historical change.’ And out of this urgent sense of passing Welsh time would come not only his finest book but the whole sequence of novels that makes up The Land of the Living. Emyr Humphreys has described himself as a chronicler of Welsh life – and these are chronicles and commemorations on an epic scale – but the term chronicling doesn’t really do justice to what these novels attempt, or what they are like: for they are always equivocal, often unflinching, consistently even-handed, endlessly ambiguous, and ruthlessly ambivalent and questioning. This is history captured in all its tentative messiness, seen through the prism of individual lives and without the comforting fiction of teleology or final judgement. There is a civic, almost familial impulse here, the same generous act of my grandmother telling me stories in her kitchen – trying to record a version of lived history for me before it was lost – but also an exploration of the different versions and meanings and legacies of that history.

There is a moment towards the end of Outside the House of Baal, where the two main characters, the minister J.T. Miles and his sister-in-law Kate – together with Kate’s brother, Dan Llew, and niece, Gwyneth – are driving near the site of Kate’s old home, a family farm called Argoed. The farm itself has been sold to property developers by Dan Llew. The ‘Old House’ has been pulled down.

‘Think of them changing the name, J.T. said, bearing his weight on the strap as he leaned forward.

Names got nothing to do with it, Kate said abruptly.

She seemed to resent the fact that J.T. had joined in the conversation.

Well it has, you know, he said.

He pulled on the strap so that his back straightened.

All the past is in a name, he said. What else is there left? Names. They’re very important. Words. Argoed, Argoed, y mannau dirgel … The man who wrote the first history of the Tudor family was born in that old house. Elis Grufydd his name was. He lived through the siege of Calais.

In the Old House? Kate said.

There’s every reason to believe it, J.T. said.

Well I was born and bred on the place, Kate said, and I never heard of it.

There was an article about it, J.T. said. In the thingummy transactions.

Outhouse really. Just a shelter for feeding-store cattle. That’s all I remember it. And as a slaughter house of course.

That was centuries ago, J.T. said, raising his voice.

All right, Kate said. We haven’t all had as much education as you’ve had.

She turned her head to look at Gwyneth.

Not everybody’s interested in history, she said. We can’t be forever living in the past.’

Now there is no doubt who Emyr Humphreys would be agreeing with if he was in the car. J.T. voices what are plainly his own political and cultural beliefs – how he saw the embracing of Welsh history and the Welsh language as unlocking the traditions and meanings of the Welsh landscape, and indeed how their embrace made the survival of Wales as a nation possible. As often in Humphreys’s work, mythical allusion and literary reference add a layer of significance, a subterranean parallel and contrast. The name of the farm, Argoed, is the title of T. Gwyn Jones’s poem (from which J.T. is quoting). The poem is about a tribe in a remote part of Gaul living a traditional and pastoral life whilst, unknown to them, the Romans have conquered the greater part of the country, destroying its language and customs. Only when the poets of Argoed go out to sing its praises, and are met by derision and incomprehension, do they realise what has happened. In the end, the people of Argoed set fire to the forest rather than submit to foreign rule. Words and traditions matter. Names matter. They are worthy of the most heroic gestures of defiance and defence.

But then look how Emyr Humphreys shifts onto the back seat to allow this contrast between the mythical history of the poem and the rather tawdry present of the scene to be complicated. Firstly, it is J.T. who is making it, a character whose idealism is a highly ambiguous virtue; at different times in the novel it can veer dangerously close to the quixotic, the moribund, or, at its worst, the positively harmful (to those around him, at least). And that choice of phrase – ‘thingummy transactions’ – is inspired: it slyly admits a hint of antiquarianism, of dusty irrelevance. And then, of course, the contrast is challenged directly in the scene by the brusquely pragmatic Kate. In the place of poetic myth and words and names and thingummy transactions, she offers a more practical version of history, a more lived experience of it (does is not matter just as much that the Old House was a stock shed and slaughterhouse as well as somewhere an old historian lived)? Kate says she isn’t interested in J.T.’s valorisation of history. But in the pages before this passage she has been recounting her own memories of Argoed to Gwyneth, and through those recollections given us a moving example of the inescapable pull of memory and the urgent need to transmit it. And finally, sitting in the back seat with J.T. is Dan Llew – the unsentimental and unscrupulous materialist who sold the farm to the developers – who is now suffering from dementia and trapped increasingly in the very past he has sold off. The man who has despoiled the secret places is doomed to return to them. The woman who says she is not interested in the past cannot stop herself passing on her memories of it. The past is salvation and dead hand at once; the life buoy and the sinking ship.

For Faulkner, the past is a shallow grave, the hasty cover-up of a terrible crime and sin – the earth barely covers it, and the moral rot and decay keeps seeping up into the air of the present like swamp gas. For Emyr Humphreys, it is buried a little deeper. But for both writers there is a sense that history not only informs the present but potentially deforms it. We see an example of this in the gothic distortions of his short story, ‘Penrhyn Hen’, from the collection Ghosts and Strangers. Here the ‘Old House’ has become a living tomb, presided over by the Miss Havisham-like figure of Malan, with her old testament vision of the wages of sin. Upstairs lies her paralysed (and equally disturbing) husband, Ritchie, whose neck she has broken by pushing him into a decaying granary in retribution for him impregnating her sister, Sioned, many years before. In the story, Malan entices Sioned and her husband Bryn back into a grotesque web of family history. The farm, described as ‘obsolete, sterile, deserted’, quickly shatters the romantic idealism of the innocent Bryn, who initially pictures it as the virtuous heartland of the gwerin. ‘She lures you here with her fancy Welsh and a lot of claptrap about the great inheritance,’ Sioned tells him, ‘and where does it leave us in the end … it’s a trap. That’s all it is. A trap.’ He has, she accuses him, locked himself up ‘in a dream of a Wales that never was on land and sea’. This is very Faulknerian territory: estrangement, violence, and entrapment lurk in all the corners of the old houses. And alongside Faulkner, Emyr Humphreys gave me a sense not just of the history of a place but of how history operates in, and shadows, a present; how it is continually shaping it, warping it, haunting it. And with that came an enabling idea of the ways the historical can operate in fiction. ‘The past,’ as Humphreys put it in an interview, ‘is a dangerous sea in which we swim.’ It is the lock and the key.

In his brilliant poetic interpretation of Welsh history – The Taliesin Tradition – Emyr Humphreys remarked that, ‘To understand a nineteenth-century Welshman, and indeed for a twentieth-century Welshman to understand himself, it is essential to know to which denomination or religious sect his immediate ancestors belonged.’ Now I must admit, I’m not sure what Calvinist Methodist says about me, but I do know that Humphreys’s depiction of the long sunset of non-conformist Wales has brought me closer to an understanding of my grandmother’s mysterious other life than any history book has, just as a A Toy Epic illuminated my father’s childhood for me in a way I can’t imagine another novel doing. I can see my grandmother – a mixture of Kate and her sister Lydia, with a bit of the younger Amy thrown in too – walking and talking in scene after scene of Emyr’s books, backlit by the slow, ebbing light of Welsh time. I catch her in glimpse after precious glimpse. And that is a gift only a writer can give.

*

‘We are a pattern-making people,’ says the character Lucas in the novel Flesh and Blood. And it is worth considering some aspects of Emyr Humphreys’ own pattern-making, his style, for it speaks – so it seems to me – both to his view of character and history, and to his view of his own role as a novelist. Within that patterning and style lies a startlingly consistent aesthetic vision and purpose.

The stripped-down language, the short, charged, compressed scenes, the apparent detachment and lack of authorial explanation or explication – we know right away when we step into the pages of Emyr Humphreys’s mature work. It feels like we’ve stopped beside a gap in a hedgerow surrounding a cottage (or manse, or townhouse) and are looking in at, and overhearing, some family drama going on in the backyard, a significant and slightly intensified moment of life. We look, but we don’t leap. There’s no sense that as readers we get to climb completely inside the skulls of the characters. We are some distance away from Henry James capturing the subtle modulations of individual perception and consciousness, or Joyce stylistically capturing its stream. We see how characters act; why they act is left to us to infer. You will not find too many analyst’s couches in the rooms of Humphreys’s fictional mansion: actions and choices reveal, but what they reveal is inherently provisional and open to qualification and interpretation. They are presented to us, and it is up to us to make what judgements we will. There can be few more even-handed authors when it comes to their characters – their flaws are often their virtues; their virtues are often their flaws. Human character is messy, contradictory, endlessly elusive.

This is what Emyr Humphreys is talking about when he speaks of the essential mystery a novelist is working with. ‘One of the impulses to storytelling,’ he says, ‘is an awareness of the mystery of human life, and the writer is attempting always to catch and convey a glimpse of that mystery.’ In the end there is always something you cannot pin down. There are no omniscient narrators here, and no omniscient readers either. If you think of one of his most compelling characters, J. T. Miles, there is never a point where you can quite decide whether he is a holy fool, or just holy, or just a fool. In Outside the House of Baal J.T. wishes to embark on a mystery tour of North Wales – as readers we follow him on a similar tour of the human condition. As Humphreys put it in an essay, referring to the work of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, ‘Human life for them was not merely the raw material of art; it was a strange sea in which humanity thrashed about like a powerful, bewildered whale, harpooned by death, and still consumed with a desire for immortality.’

This is what Emyr Humphreys is talking about when he speaks of the essential mystery a novelist is working with. ‘One of the impulses to storytelling,’ he says, ‘is an awareness of the mystery of human life, and the writer is attempting always to catch and convey a glimpse of that mystery.’ In the end there is always something you cannot pin down. There are no omniscient narrators here, and no omniscient readers either. If you think of one of his most compelling characters, J. T. Miles, there is never a point where you can quite decide whether he is a holy fool, or just holy, or just a fool. In Outside the House of Baal J.T. wishes to embark on a mystery tour of North Wales – as readers we follow him on a similar tour of the human condition. As Humphreys put it in an essay, referring to the work of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, ‘Human life for them was not merely the raw material of art; it was a strange sea in which humanity thrashed about like a powerful, bewildered whale, harpooned by death, and still consumed with a desire for immortality.’

And the patterning of Emyr Humphreys’s work tries to frame that thrashing about, to give it a form; to hold it poised in snapshots, like family photographs pinned (or perhaps harpooned) to a board. The historical novels, especially, are structured like narrative collages, working through juxtaposition and accumulation, an ever-extending and more intricate kaleidoscope. And if juxtaposition implies space, so accumulation implies time: as we move through the significant fragments of a life (and lives) we see how the past informs the present; there is recurrence, the persistence of patterns, or threads within patterns, or patterns within threads. For example, in a short scene in Outside the House of Baal, we see Kate visiting her son Vernon in his squalid flat in London. Vernon’s wife pleads with her to convince her son to put the needs of his family above the impractical idealistic impulses he shares with J.T. The ambiguous virtues/sins of the father have been visited on the son. A thread unravels across one generation into another. As Wynn Thomas has put it ‘… the novels are elaborate, complex structures of ambivalence, ambiguity and indeterminacy.’ This, as T.S. Eliot described it in The Four Quartets, is ‘the pattern more complicated’.

As I get older, I find that my own style, my literary language, rather like my skin, has begun to retract and show the bones beneath; it has taken on a certain starkness or gauntness. I think that happens with some writers. I suppose you start to realise you’ve only got a limited amount of words left and so spend them a bit more wisely. For Emyr Humphreys this economy, this minimalism, came early, and is a purposeful constraint, one that the novelist has imposed upon himself. We can perhaps see this most clearly when we contrast it with his characters. Many of them are awfully garrulous (especially the men); they are spendthrifts with language, out on a spree. And what we often hear is the flotsam and jetsam of different ideas and ideologies washing up on time’s shore while the author remains just out of sight over the sand dunes; a wry, almost invisible, listener and watcher, wary of rhetoric, of acceding to any single or all-encompassing view. Humphreys does not win arguments in his fiction, he shows people having them. This what they say, this is what they do, this in the end is all we can know.

During his time in Italy after the second world war, Emyr Humphreys said he developed a ‘balcony view of life’. Yet as a metaphor or figure for authorship, this balcony view of life isn’t a romantic notion of artistic isolation or transcendence – the Joycean aesthete paring his nails over his creation – but a form of inclusive, balancing, complicating detachment. It seems to me there is a profound humility in this style: a rare gift for restraint; a preparedness to let his material speak. It shares the quietly subtle self-effacement of the translator or interpreter.

*

Emyr Humphreys has described his style – with a characteristically mischievous, tongue-in-cheek humour – in terms of a kind of regional aesthetic, characterising the hewed down lyricism of his writing as a version of North-Walian laconicism, a prose echo of ‘the epigrammatically terse Welsh poetic tradition’. He distinguishes it from the more flamboyant (and perhaps implicitly exhibitionist) tendencies of the tradition of writers from the South-East he called the Glamorgan School, and their ‘endless golden eloquence’. But behind this playful distinction there lies a serious question: how to avoid the risk of ‘performing’ Welshness in English (and for an English audience)? Humphreys’s style speaks directly to the central conundrum of his writing: how to translate the experience of characters living in one language and culture into another language (the very language that has historically threatened them – the colonist’s iron and seductive tongue)? ‘… by being minimalist’, he has said, ‘I try to minimise the distortion involved in this kind of cultural ‘translation’. So I try to turn the weakness into a strength, using this kind of stripped-down English is an effort to capture the quintessence, as opposed to the general texture, of the Welsh life with which I am dealing.’

Emyr Humphreys grew up a few miles from Offa’s Dyke. And straddling a geographical border, he also straddled a linguistic and cultural one: he would go on to become fluent, and live his life in, Welsh, and to discover many of his cultural heroes amongst the golden age of Welsh language writers and activists of the 1920s and 30s – Saunders Lewis, Kate Roberts, Ambrose Bebb, and W.J. Gruffydd. Border writers are good at translation – it is a constant and necessary act; it’s what they negotiate (internally and externally) all the time. They must be careful of possible confusions, of multiple allegiances, of people looking warily, and sometimes suspiciously, from both sides. They have to get used to being inside and outside at the same time. I would say Humphreys turned that condition into an incredibly elastic and generous aesthetic of in-betweenness. It is something I have come to admire more and more.

*

Looking back, I can see how many of the themes that permeate my own writing, whether set in Anglesey or Canada, are already encompassed in Emyr’s work (mountains, after all, cast long and wide shadows): the relationship between insider and outsider, cultural collisions and frictions, the gothic shapes of a past that will not lie still, the preoccupation with inundation – in mythical and actual forms – and of land that is not quite secure or solid, the tension between the twin desires for mobility and rootedness, between islands and mainlands. None of this similarity is surprising. These are border themes. Perhaps the one slight difference is a matter of geography: in that my own border is the Atlantic Ocean rather than Offa’s Dyke.

I remember being plonked down in the playground of Llangoed primary school at the age of six and being immediately accosted with the question, ‘You Welsh or English?’ It was a difficult question for me. I wasn’t English, and it had barely even occurred to me what Welsh meant – I had never been here before; I had just met my Welsh grandparents and discovered my father spoke another language. I didn’t know what to say, and for three years I barely spoke at all. And behind that long silence was a fear that to speak was to fix myself in one camp or the other, to place myself in one corner of the playground, to take a side in an argument that had been going on for a very long time and that I hadn’t started and didn’t understand. Ever since, I have been exploring what answer I might have given. I’m not sure yet. But through Humphreys, I discovered an example of what it could be like to keep standing in the middle of that playground, a model of what a border writer might be – of the creative opportunities and tensions, but also the sense of expansion: how being conscious of one border means being conscious of multiple borders – of the view widening and widening.

Emyr Humphreys saw himself as a European writer, as a novelist in the tradition of the great European novelists. To be a Welsh writer was, for him, to be a European writer. His Wales did not make sense without Europe; as a writer and a thinker that was the way out of the rusty old bars of Offa’s Dyke. To return to that quotation from Faulkner about postage stamps of native soil: postage stamps are vehicles of connection and there is no such thing as native soil – the grinding, shifting, colliding tectonic plates that created it are continental, are global. A handful of dirt has the whole world in it. My own Wales does not make sense to me without Canada: through me, it borders there. And through others it borders India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Somalia, Ethiopia, China, Guyana, Japan, Patagonia … it borders almost everywhere.

Humphreys has a special fondness for those magical cauldrons of rebirth and inspiration that bubble away in the halls and kitchens of Welsh myth. In The Taliesin Tradition, he uses one as a metaphorical vessel for Welsh cultural formation and re-formation, for the crucible of myth itself. It is kept on the boil by fires ‘kindled by Saxons, by Danes, by Vikings, by Normans’, fed with ‘a steady sequence of triumphs and disasters, splendours and miseries,’ and mixed ‘with ancient material from a pre-Christian past, from the Old North, from Ireland … from all the Lost Kingdoms.’ This cultural stew, drawing on pasts, presents, and futures – all curiously intertwined, both imagined and remembered, made of history and poetry and prophesy – feeds the remarkable Welsh appetite for transformation, persistence, and ‘creative survival.’

And indeed it is one of those very cauldrons, belonging to a witch from Bala called Ceridwen, that in a roundabout fashion gives birth to the second, mythical and folkloric, incarnation of that book’s hero – Taliesin. For Emyr Humphreys the survival of Wales as an idea depends on that shape-shifting version of Taliesin, on his genius for adaptation, for finding new forms and combinations and voices, for turning up in fresh disguises. Every time a new Albie or a new Michael or a new Iorweth introduce themselves, the corners of Wales – as they always have – will multiply.

Tristan Hughes is an award-winning writer whose most recent novel Hummingbird (Parthian, 2017) won the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Award and the Wales Arts Review Wales Book of the Year People’s Choice Award.