Josie Cray explores the compelling artwork of Cerys Knighton, whose exhibition Bipolarity was recently on display at The Gate arts venue in Roath, Cardiff.

‘I wanted to tie a figure together with nothing but pen and ink’

How do we understand bipolarity? How might we make sense of a mental illness that often leaves those with it confused, overloaded, and unsure when they can safely situate themselves in reality? How might those suffering seek therapeutic spaces that allow them to unpack their experiences and find a voice to communicate their own stories?

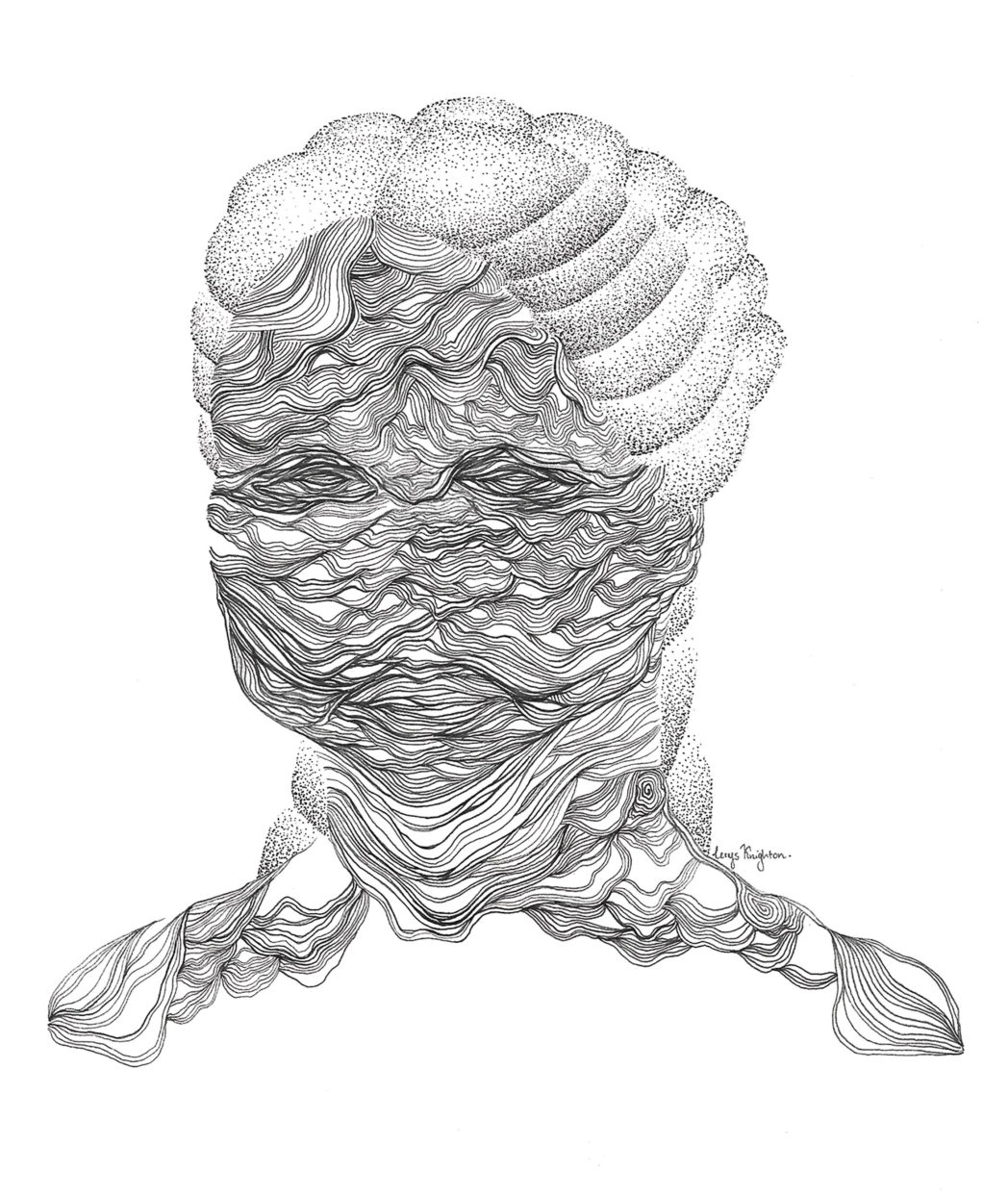

Cerys Knighton delves into these questions and more in her current exhibition ‘Bipolarity’. Knighton’s own experience of bipolarity informs both her artwork and her current doctoral research, with a unique conversation taking place between past and present, medical case studies and drawn images, research interests and personal experience. Knighton makes use of pointillism, a technique in which thousands of individual dots are organised, layered, and graded to build larger, more intricate images. Using dots to create shading, lines which appear to float in the wind, and the texture of animal fur and features, pointillism is a method which requires patience and focus, with startlingly haunting effects in Knighton’s work.

Knighton herself began drawing as a child as ‘a way of recreating [her] experiences of hallucination and dissociation’. She describes how much of her own artwork ‘was full of my own terror in a desperate attempt to understand what was happening to me.’ Pen and ink became a tool for her to tie herself together, ground herself after bipolar episodes and make sense of her experiences. After her own diagnosis, Cerys Knighton returned to drawing: ‘I decided to try and draw my experiences in a way that could allow me to understand what I was feeling. I wanted to draw wonder as well as darkness, and tried to recreate emotional expression through depictions of wildlife and nature’.

The exhibition itself falls into two narratives: images from Knighton’s earlier collections which chronicle her more personal explorations of bipolar disorder, and more recent images which are inspired by, and are in dialogue with, her doctoral research.

The personal narrative develops around the relationship between decay and restoration—a relation Knighton depicts as non-linear, where subjects can be read as progressing from one state to the other at any given time. Breaking with her usual pointillism style, ‘Llwynog – Hiraeth’ (below) depicts a fox looking over its shoulder.

Inspired by the Welsh idea of ‘hiraeth’, Cerys Knighton uses the fox—brilliantly textured through the layering of colours to create fur—to explore what hiraeth means for her. ‘Hiraeth,’ she explains, ‘can invoke the sensation of missing something that no longer exists, a person, even a state of being. I wanted to find a way of drawing what hiraeth feels like to me as the sense of feeling a part of myself slipping away within my own mind, when it starts to feel less and less like my consciousness is my own.’ The glassy eye of the fox is inspired by Knighton’s own dog, Luna—a way for her to ground herself or locate her reality in a mental illness that often distorts reality and leaves Knighton with cognitive issues and issues with memory. The fox with Luna’s eyes suggests a looking back, a reflection upon our own situation, our own state of being.

Subject matter across Knighton’s collection focus around nature, animals, and the body—all of which connect with the idea of decay and restoration that threads its way through her images. The boundary between body and nature is blurred as in ‘Lung’ (above). What initially might look like a rock with moss or lychee crawling its way across, and the roots of a tree grappling the rock come to be understood as the structure of a lung and oesophagus. Vessels and air sacs mimic the mould and fungal growths of a forest floor while the oesophagus roots its way into the lung, spreading into the structure. The detail and grading of Knighton’s pointillism here makes the image feel as if it is moving. Minute veins snake across the lung as it seems to contract and expand in front of us.

The focus on the internal structures of the body, organs and bones, hints at a biopolitical focus in Knighton’s work. Often, mental illness is treated through the use of medication, chemicals which infiltrate the body to restore some version of a stable reality to those with bipolar (and other mental illnesses). However, ‘Lung’ suggests that the expectation for medication to ‘fix all’ might be an uncertain one. Cerys Knighton describes how her own experience with medication has left her somewhat not herself, unable to control how her body reacts to the chemical changes it is under the influence of.

The second narrative which takes shape across the exhibition is the conversation between the artwork and Knighton’s doctoral research. Knighton’s research explores representations of manic-depressive illness from 1830-1930, with one focus being the ‘significant change in the treatment of nineteenth century mania from bodily restriction, limited diet and blood-letting to a focus on open air, exercise and nutrition’.

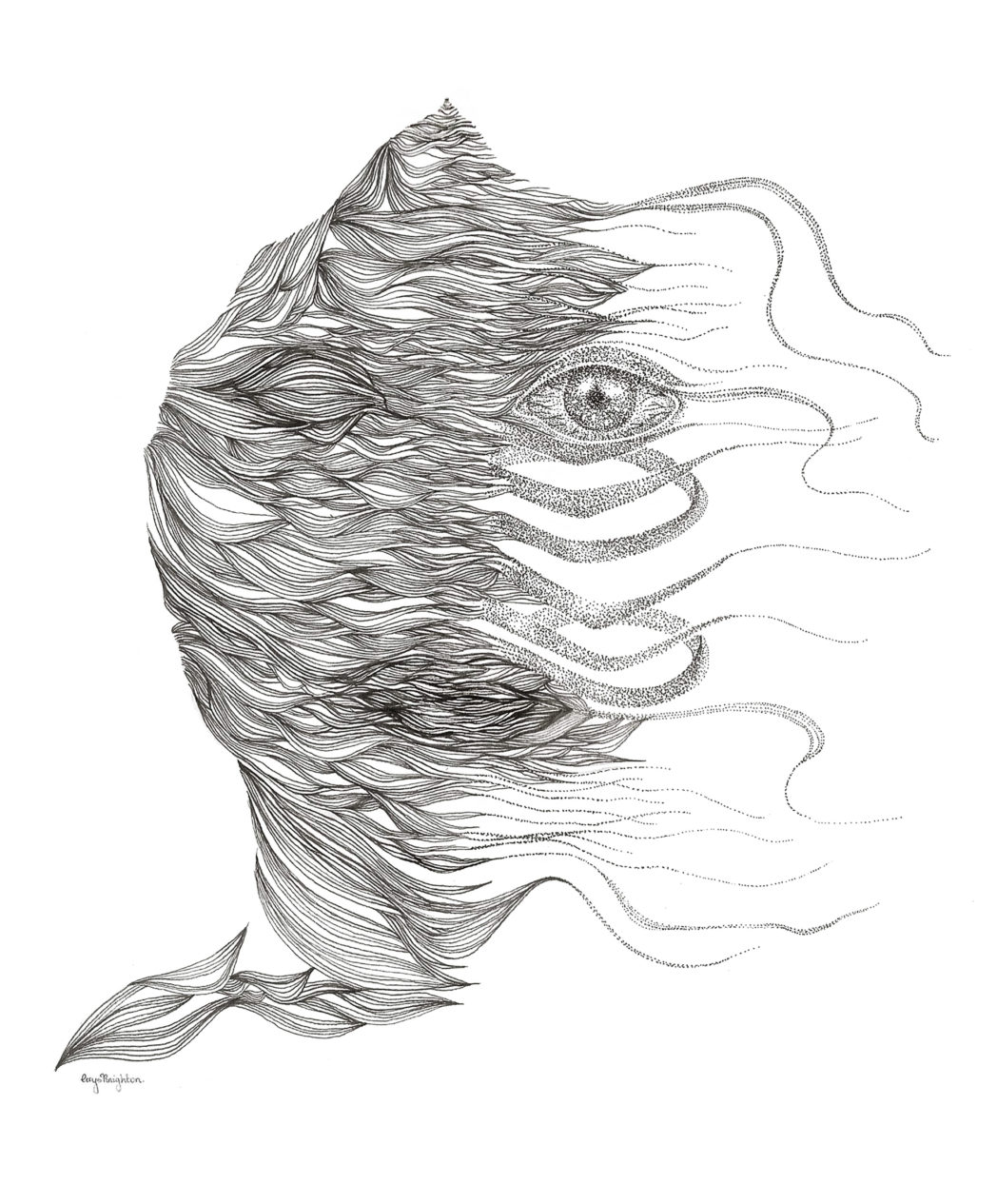

Drawing upon a medical article of the same name published in The Lancet in 1841, ‘Bodily Restraint is Imperative’ (above) is in conversation with the debates around the effectiveness of restraints the in the treatment of mania that were taking at the time. Knighton makes use of a mixture of lines and graded dots to produce the image of a woman. Lines ebb and flow across her face, densely packed to give the appearance of muscles to create what Knighton describes as ‘a sense of being tightly bound down to the muscle texture’. The lines which create muscle texture converge around the eye and lip areas suggesting something is missing, someone is missing—identity is removed through the hauntingly empty eyes and frowned missing lips. Graded dots disperse into layered, braided hair adding another textured dimension to the portrait.

Knighton’s research has uncovered complex discussions around the treatment of patients with mental illness, describing them as the ‘Frontiers of Medical Treatment—a name shared with the first image in this piece. Letters to The Lancet, Knighton has found, have argued that even ‘the most insane are not without their moments, their hours, and even their days and weeks of reason,’ and as conversations around the treatment progressed into the mid-1800s doctors moved away from restraint toward different, more creative approaches.

‘The Dancing Manic Patient’ (above) was inspired by a case in Knighton’s research where a patient’s mania had progressively worsened under the then-current restrictive treatment. In contrast to restraints, the doctors used a freer, creative approach to help treat the patient’s mania. Knighton explains how ‘the medical attendants play[ed] the violin and let the patient dance to focus his excitement. As a result, he “slept during the night” for the first time “since his admission”, as well as requesting food’. Lines dance across the paper forming the shape of a body freed from restraint. The violin, now the head of the body, bursts forth with green vines, connecting to Knighton’s personal works that explore decay and restoration. We might consider how the more creative approach to the treatment of mental illness, the use of the music and dance, provides a space for restoration for this patient. The green vines dance across the white paper, contrasting with the black and white line and dots, suggesting growth and life.

Knighton’s research, though focusing on medical treatment between 1830 and 1930 draws attention to the conversation that is currently taking place around our current treatment—medically, culturally, and socially—of people with mental illness. Many of the images in the exhibition become focal points to discuss the intricate relationship between past and present in medicine. Cerys Knighton makes a point of highlighting in her artwork and her research the importance of reflection—individual reflection and larger, social reflection—on the treatment of and stigmas placed upon those with mental illness. The artwork draws the past into the present, asking us to reflect upon misinformation and stereotypes we have inherited and still perpetuate; the images shed light on a discussion of biopolitics often overlooked in debates today around the medicinal treatment of people with mental illness. We might ask ourselves: How do we understand mental illness? How might we learn from the past to create safer spaces for those who may suffer in the future? How can we, individually and as a society, reflect upon the traumas of the past and support those who experiences mental illness in the future? Knighton ties these discussions and more together through pen and ink, intricate work which ask us to both look closer to see the details and stand back to reflect upon the whole picture.

Cerys Knighton

Cerys Knighton’s future exhibitions take place October 2020 at Redhouse, Merthyr Tydfil, with an open evening scheduled for the 10th of October (which will be World Mental Health Day 2020) and June-July 2021 at HeARTh Gallery in Llandough Hospital, Cardiff.

Josie Cray is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.