Lambing, hunting, forestry, fishing. A dead fox, a bleached skull, a crow. In Nicky Arscott’s large painted panels these icons of rural life in mid Wales are rescued from the banality of cliché to confront us with all their original resonance. Here is birth, life and death up close, and the portraits remind us – even if the townies among us would rather forget – that we are subject to the same forces of change as the rest of nature.

Arscott calls the exhibition a ‘large-scale poetry comic’ and each painting relates to lines in a poem called ‘Soft Mutation’ (published in her pamphlet Soft Mutation by Rack Press in 2015). The lines from the poem are written across/through the panels in the original English and in Hywel Griffith’s Welsh translations. In this way she weaves language into her cosmos of birds, fish, horses, trees, bones, hunters, farmers, children. If the symbiotic relationship between image and word is a strong element in the Welsh tradition (see, for example, Imaging the Imagination: An Exploration of the Relationship Between the Image and the Word in the Art of Wales, edited by Christine Kinsey and Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan), it is foregrounded in the work of this hugely talented visual artist who is also a poet and creator of comics.

‘Soft mutation’, of course, is the name for the way the initial consonant of a Welsh word may change in accordance with grammatical rules. There is also mutation in translation from one language to another. But Arscott’s fascination with the term goes beyond the linguistic. In her rendition of life in the countryside, everything is mutating and changing state: being born, growing old, dying, decaying.

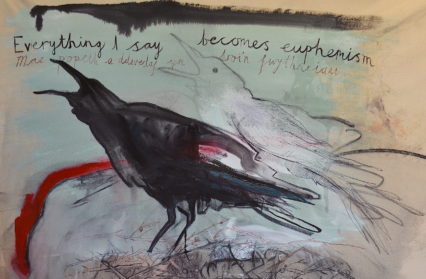

The softness of these natural mutations, though, is challenged visually and verbally in these striking paintings where a central figure (usually human, sometimes human with animal, sometimes animal alone) is drawn in thick black lines and daubed with colour – blues, reds, oranges. Fierce energy and movement persist in the brush-strokes, and although there is often a background suggestion of delicate patterning – patches of wallpaper, flowers, leaves – these serve to enhance the presence of something powerful and dangerous. Vulnerability to violence and decay, the paintings suggest, is a condition of being animal.

The figures in the paintings often display a sense of restricted movement. There’s a prone sheep caught in thorns, and a pregnant woman leaning uncomfortably against a wall (‘The blackthorn grows around itself sending suckers out then dying inside’ say the words). The farmwokers are ‘inflexible men in overalls the colour of pine’ and a boy in a blue Puffa coat, hands held firmly by his side as though he’s forcing himself not to touch, stares down at the decaying carcass of a fox.

It’s worth taking a closer look at the heavily pregnant woman. She is pushing against the wall with one hand and pressing the small of her back with the other. Is the expression in her eyes one of pain, or terror, or anger? Is she in labour? Artists – mostly male – have often indulged in the romantic notion that the creation of a work of art is like giving birth. Real birth, however, hurts like hell and involves lots of blood, sweat, shit and tears. Real rural life is not just about pretty views and beautiful landscapes – it’s also about work, care, and violence.

The originality and power of Arscott’s work is the way her pictures seem to contain multiple viewpoints. Her identification is not solely with the sheep farmer, or the fox hunter, or the river bailiff (although she represents these people as central to the rural landscape), but also with the young child confronting death, with the newborn lamb itself, with the dead fox, with the sheep caught in thorns. The shimmering white wool of a lamb demands as much of our attention as the tattooed arm of the man who holds her; the fox fur which clings to the hunter’s rifle reminds us of its killing function. And perhaps this is the soft mutation at the heart of Arscott’s work – her ability to shift identification. It is an ability at the core of empathy, and of caring.

Fierce caring is therefore another aspect of rural life woven through these pictures. The sheep farmer cradles one lamb in his arm while bowing over another to feed it (‘i deimlo pob marw i’r byw; a gneud hynny erioed’/’to count each death personally; to have always done so’). The roots of the words cultivation, culture and care are the same. Farming, raising children, painting pictures, writing poems – these are struggles framed by our vulnerability to forces beyond our control. In Arscott’s paintings of Llanbrynmair, the struggle is a visceral dance.

Llanbrynmair – Soft Mutations – Nicky Arscott

MOMA Machynlleth http://moma.machynlleth.org.uk/

23 September 2017 to 02 December 2017

Accompanying comic book published by Mother Mary Press.