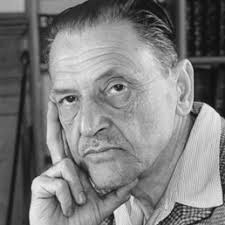

Somerset Maugham. A voice not just from another century but from a musty part of that century. As lionised in his day as Hugh Walpole, Charles Morgan or Warwick Deeping – albeit wealthier – Maugham is now as much remembered for the grandeur of his home, the Villa Mauresque in Cap Ferrat, the toxicity of his marriage to Syrie, or his other unintended part in literary history, a source ripe for pastiche for Anthony Burgess in his epic Earthly Powers of 1980.

Maugham is a rare example of the author who successfully straddled novel, short story and drama. He came my way from two directions. The BBC made a series of adaptations of the short stories and I would join my parents to gaze at tales of steamy colonial betrayals, disgraces and deaths. Maugham’s characterisations are rough-cut but his tales from Malaya still feel authentic in their depictions of lives numbed by routine, social boredom, racial and sexual discrimination. Their only true literary counterpart is Burgess’ own Malayan Trilogy of the later 1950s.

Gainsborough Studios made three films between 1948 and 1951, portmanteau collections of three or four stories packed with every leading name from British theatre. Nigel Patrick plays the eponymous ‘Mr Knowall’ in the middle film Trio. On their television showing years later I wondered over the name of the character’s name ‘Kelada’ as it obviously read ‘a Dalek’ backwards. The first of the films, Quartet, features a young Dirk Bogarde in a story called ‘the Alien Corn.’

The second route came via the three volumes of Maugham’s short stories, sixteen hundred pages bound in red that occupied five inches of bookshelf in our front room. ‘The Alien Corn’ appears as second story in the second volume, its lead character a privileged scion of a wealthy family, George Bland, who rejects the family parliamentary seat in favour of ambitions to become a professional pianist.

‘The perfect type of a English gentleman’, observes the narrator, undergoes two years of intense immersion and dedication. His hair grows long, his nails are rimmed with black, and his Oxford Bags become grimy. A self-absorbed professional of the piano arrives to deliver her verdict. ‘Art is the only thing that matters’ she declares. ‘In comparison with art, wealth and rank and power are not worth a straw.’

The narrator espies George’s hands ‘I was astounded to see how podgy they were and how short and stumpy the fingers.’ They are not the hands of a pianist, declares the judge and maestro of the instrument, and he lacks the ear. ‘I don’t think you can ever hope to be more than a very competent amateur’ is her verdict. ‘In art the distinction between the amateur and the professional is immeasurable.’

Claire, the youngest sister in Brian Friel’s play Aristocrats, has similar ambitions and similar dismay. Her response is a tough-minded realism, that she will be ‘a good, but not a great pianist.’ In the nature of Maugham’s fiction George gives his father a kiss on the lips – ‘a strange thing’- and goes to the gun-room. In preparation for the shooting season he proceeds to clean a gun unaware that is loaded. It is not so far from reality. Peter Biskind in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, his study of US cinema’s peak, reports that the brother of Terrence Malick, a student of classical guitar in Spain, died by apparent suicide.

For a few crucial years, around age fifteen onward, fiction and fables make their deepest mark. Direct experience then takes over. For an inward teenager ‘the Alien Corn’ hit home. It said that wish and will are in themselves insufficient. Life choices as they turn out may be second, third, or even fourth best.

Experience reinforced the message of fiction. A couple of years on, while hitch-hiking home from the Gower, I was picked up by a driver who said that he had wished to be an optician. Insufficient family means had instead meant an unglamorous life in vehicle testing. A few months after that and I was on a bus between Der’aa and Damascus. The uniformed conscript in the older Assad’s army standing next to me said his deepest wish was to practice taxidermy. ‘But there is no work for a taxidermist in my country’ he said wistfully.

That the world was never designed with our personal convenience in mind is a moral lesson that comes to all. The later it comes, the more shaking is its impact. On re-reading ‘the Alien Corn’ it is rambling and ill-structured, distasteful in its racial stereotyping. But back then, in the hands of a teenager who knew nothing, it was bearer of a message of might and truth; all know disappointment.