In a major new feature, inspired by the outpouring of affection for To Kill a Mockingbird following the publication of the new Harper Lee novel, Wales Arts Review has been asking our writers to name the moment that shaped their lives in those most impressionable of years, that teenage wilderness. The choices are diverse, eclectic, and as inspiring now as they were then.

You can join in the Teenage Kicks discussion with Wales Arts Review on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram using the #TeenageKicks hashtag.

~

Wales Arts Review’s Teenage Kicks:

John Harrison – The Great Gatsby

1974 was my graduation year, and the summer of Robert Redford playing Jay Gatsby opposite Mia Farrow. After a year of working through university vacations I wanted a breather. I had no clue what I wanted to do, and would not for another twenty seven years. I was living in Cornwall, and spent the summer road-sweeping in the sunshine and going to the beach after work.

One afternoon, after a blistering day pushing tourist litter into piles, and dog-shit down drains so it wouldn’t stink out my cart, I went straight from work to see the film. 146 happy minutes later, I came out into the sunshine to see, queueing for the 6.30 performance, the French exchange student I was desperate to date. My filthy clothes would probably not have sunk me if she hadn’t been with friends, who assumed this was how I always dressed.

One afternoon, after a blistering day pushing tourist litter into piles, and dog-shit down drains so it wouldn’t stink out my cart, I went straight from work to see the film. 146 happy minutes later, I came out into the sunshine to see, queueing for the 6.30 performance, the French exchange student I was desperate to date. My filthy clothes would probably not have sunk me if she hadn’t been with friends, who assumed this was how I always dressed.

The gorgeous cheekbones, so strong they cast graphite shadows like Julie Christie’s, were never taken into my palms for me to close on the heartbreak promise of her lips. Instead, I bought the paperback novel and the soundtrack LP, and sang ‘Who Stole my Heart Away?’ I read the book twice, then devoured everything else he had written. Tender is the Night is the subtlest achievement, but it was Gatsby I returned to, reading of youth, beauty and hope. Gatsby’s driving force is also his central flaw: the power of his unrequited love.

Despite the crass marketing behind the 2013 film, the story isn’t about parties. Fitzgerald was in his 29th year when he published Gatsby and the flapper novels were behind him. He now viewed youth’s idealism from the far side, and showed, not that it was misplaced, but that it was fatal to carry it through life unexamined.

TS Eliot thought it the most interesting American novel for some time. It rang with the clarity of images and beauty of language that Eliot, like Fitzgerald a Mid-Westerner by birth, created in his own poetry. Fitzgerald had devoured Keats; Already with thee! tender is the night. Fitzgerald didn’t write floridly, but from Keats he learned how to couple intense language with clear ideas.

Forty years on, completing my new book on Mexico, and considering the discovery of America. I fell back on Fitzgerald’s matchless reflections in Gatsby’s closing pages. Such sentences remain a model for me: ‘for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.’ America is also Gatsby’s lover. The shallow Daisy never deserved the grandeur of his desire.

Researching this I found my partner shares her birthday with F Scott Fitzgerald: a charming surprise. But sometimes, I think of Gatsby and 1974, and a French girl’s cheeks turned by candlelight into shadows of desire.

(John’s new travel book 1519 A Journey to the End of Time is out now: Parthian books £10.99)

Bethan Tachwedd – Kid A

My intention had been to spend the summer improving my tennis, putting in the hours towards the dream of emulating the all conquering Williams sisters and their bodacious baseline mastery. The exceedingly expensive racquet, fresh from the shop and bought thanks in part to a small inheritance from a recently deceased great aunt, was ready to overhead smash and net volley its way to glory, and so was I. Then a curious thing happened, I lost interest in becoming the long lost Welsh Williams sister and the racquet sat in the corner of my room, pristine and nothing more than an expensive door jam, perhaps representing a period in my life that was drawing to a close. Out of sheer boredom I ventured into my eldest sister’s room (she was away for the summer in Goa with friends from University) and began rifling through her things with what started out as a kind of lackadaisical indifference but became a voyage of musical discovery and liberation. I could name a dozen albums that engaged and educated me over the course of that summer, but the one I will choose is the very first one I listened to.

My intention had been to spend the summer improving my tennis, putting in the hours towards the dream of emulating the all conquering Williams sisters and their bodacious baseline mastery. The exceedingly expensive racquet, fresh from the shop and bought thanks in part to a small inheritance from a recently deceased great aunt, was ready to overhead smash and net volley its way to glory, and so was I. Then a curious thing happened, I lost interest in becoming the long lost Welsh Williams sister and the racquet sat in the corner of my room, pristine and nothing more than an expensive door jam, perhaps representing a period in my life that was drawing to a close. Out of sheer boredom I ventured into my eldest sister’s room (she was away for the summer in Goa with friends from University) and began rifling through her things with what started out as a kind of lackadaisical indifference but became a voyage of musical discovery and liberation. I could name a dozen albums that engaged and educated me over the course of that summer, but the one I will choose is the very first one I listened to.

Kid A by Radiohead blew my mind, a sonic challenge wrapped inside of a musical riddle dead set on confounding expectations from music journalists and Radiohead fans alike. It opened doors to my lasting thirst for krautrock, electronica, and just about any genre you could mention from Humppa to Mangue Bit; Kid A would rightly cement Thom Yorke’s reputation as a daring and restless innovator. Unlike so many other albums I have listened to before or after it encouraged me to ponder the great questions, something that it still does when I listen to it now; and this I believe is the true testament to the influence it had on me – that I still listen to it years and in excess of two hundred plays later, a late night soundtrack, a long distance flight accompaniment, and, of all things, the soundtrack to a tennis match with my eldest sister on a balmy summer’s evening. Kid A by Radiohead may have been my teenage album, but it really is a piece of music for the ages.

Craig Austin – Carrie

In the days when I teetered on the cusp of the cultural and biological phenomenon that is ‘teenage’, the films that I found myself drawn to tended to be steeped in the glamorous malaise of the perpetual outsider.

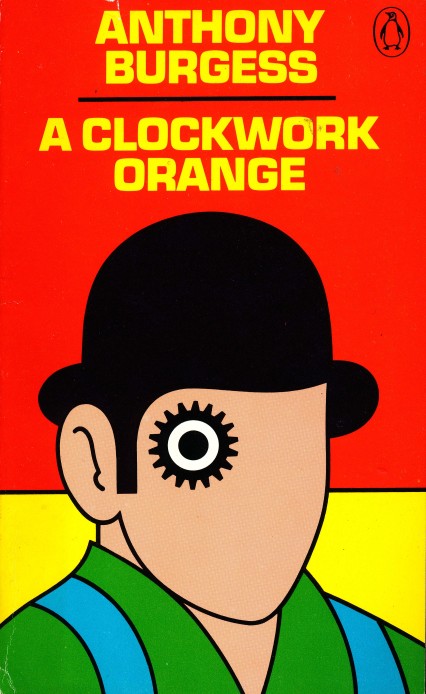

It was a period that first took in Quadrophenia (known simply within my peer group as ‘Quad’), the studied Ralph Lauren earnestness of The Breakfast Club, and the then still-unavailable A Clockwork Orange (known simply within my peer group as ‘that one that Jason’s brother got on pirate’). We were all, of course, huge admirers of Anthony Burgess’s entire literary oeuvre.

Yet when cinephiles reference the big screen’s pre-eminent ‘shower scene’, I revert far more readily to the misty locker room of a suburban American high school than I do the monochrome bathroom of a suburban American motel. A scene in which blood (menstrual blood, no less) is actually spilled in life’s perpetually brutal rite of passage, the transition from child to adult.

Yet when cinephiles reference the big screen’s pre-eminent ‘shower scene’, I revert far more readily to the misty locker room of a suburban American high school than I do the monochrome bathroom of a suburban American motel. A scene in which blood (menstrual blood, no less) is actually spilled in life’s perpetually brutal rite of passage, the transition from child to adult.

The 1976 cinematic adaptation of Stephen King’s Carrie, first viewed under the covers and via the bulbous screen of a battered portable TV, spoke to me in ways that I’d rarely previously engaged with. It’s the outsider’s outsider’s movie, a tale of isolation, paranoia and raw all-encompassing revenge; a devastating package of fantastic destruction seen via the fragile teenage worldview of its telekinetic anti-hero. It’s a horror film whose horror is not solely restricted to the slaughter of a pig or the protruding hand of a corpse; instead it’s most potent depiction of horror lies in its unadorned depiction of the teenage experience; the projection of personal insecurity via the arsenal of cruelty and spite.

The very fact that it’s fabled blood-drenched denouement takes place at the coronation of a prom queen underlines the most bankrupt elements of the archetypal teenage experience: popularity as currency/weaponry, a class system that values beauty over depth, the survival of the ‘fittest’. It’s why when Carrie White, via an extraordinary performance by Sissy Spacek, transforms her hitherto suppressed fury into a devastating maelstrom of death and destruction we stand firmly behind her.

Yes, she kills her fanatically religious (and evidently insane) mother, but who can reasonably argue that she didn’t have it coming to her? Her fate was surely cast when she spat out the words that send the iciest of chills down the spines of all teenagers: ‘They’re all going to laugh at you’.

Kaite O’Reilly – ‘Rock n Roll Nigger’

In the Birmingham-Irish backwaters in which my early teenaged body was steeped, only men used the word ‘fuck’ – and use it they did, with relish, contempt and a kind of anger, invariably directed as a weapon at the female form. We were at fault for everything. This blame and loathing was also found in my strict Roman Catholic upbringing where everything had been grand until that slattern Eve turned up, and wouldn’t we her offspring be punished for it indefinitely…. There were few positive female role models except my own fierce and fashionable Mammy, who turned a blind eye to the goings on in the front room, where all the local kids piled in, to experiment and share whatever we had found from ‘the other side’ – adulthood.

In the Birmingham-Irish backwaters in which my early teenaged body was steeped, only men used the word ‘fuck’ – and use it they did, with relish, contempt and a kind of anger, invariably directed as a weapon at the female form. We were at fault for everything. This blame and loathing was also found in my strict Roman Catholic upbringing where everything had been grand until that slattern Eve turned up, and wouldn’t we her offspring be punished for it indefinitely…. There were few positive female role models except my own fierce and fashionable Mammy, who turned a blind eye to the goings on in the front room, where all the local kids piled in, to experiment and share whatever we had found from ‘the other side’ – adulthood.

And so in the oasis of my front room a bootleg of a live gig was fed into the gaping maw of my eldest brother’s cassette tape player – and a voice of such raw energy and naked power scratched the roof of my imagination, letting me know this is what a woman sounded like.

Patti Smith’s spoken word improvisation combined with Mappleworth’s images smashed the plaster-cast virgin marys in my mind. Here was a woman who looked like a boy who looked like a girl, who owned and indeed pleasured in stating her own desire, who used the word ‘fuck’ like the celebratory sensorial act I suddenly realised it should be, and most memorably to the indoctrinated Roman Catholic, in her ‘Rock n Roll Nigger’ (the use of the ‘n’ word itself shocking and yet subversively reclaiming) ‘I feel no guilt.’

I saw here was another way of being, of looking, of making, of communicating, of creating – another form of using words politically without speechifying – by making the body move, the brain dance, and to fucking enjoy it.

Ben Glover – Elementalz

I’ll begin by saying that my teenage years were spectacularly mundane, to say the least. Most of the time I tried, often unsuccessfully, to conform to the conventional teenage orthodoxy of manufactured anger and posturing angst, in an obedient statement of my individuality. This faux rebellion mainly manifested itself through the wearing of mass marketed Nirvana/Machine Head t-shirts and unkempt long hair. In reflection, my adolescent dissention was sponsored by major record labels, cheap lager and the avoidance of the barbers (I know, I was a real badass!).

However in 1996 this all changed. With the release of their only album – Elementalz – The Brotherhood, a hip hop trio from North London, altered the way I perceived, not only music or art, but the world that surrounded me. Their bleakly subversive breakbeats cut through the thick and heavy darkness of flailing guitars and self indulgent drum solos; revealing a fascinating subculture of art, activism and language. I quickly became obsessed with all facets of my new discovery; I wanted to know their influences, the culture that surrounded them, their choice of album artwork which immediately sets the seditious tone of the album (it’s by the great Dave McKean, by the way) and other artists that had a similar process for creating their work. Subsequently, my world broadened from the narrow valley that I called home, to encompass Goldie’s Timeless awe-inspiring cityscapes, La Haine’s counterculture Paris and Public Enemy’s misrepresented New York.

However in 1996 this all changed. With the release of their only album – Elementalz – The Brotherhood, a hip hop trio from North London, altered the way I perceived, not only music or art, but the world that surrounded me. Their bleakly subversive breakbeats cut through the thick and heavy darkness of flailing guitars and self indulgent drum solos; revealing a fascinating subculture of art, activism and language. I quickly became obsessed with all facets of my new discovery; I wanted to know their influences, the culture that surrounded them, their choice of album artwork which immediately sets the seditious tone of the album (it’s by the great Dave McKean, by the way) and other artists that had a similar process for creating their work. Subsequently, my world broadened from the narrow valley that I called home, to encompass Goldie’s Timeless awe-inspiring cityscapes, La Haine’s counterculture Paris and Public Enemy’s misrepresented New York.

In retrospect, Elementalz taught me that the essence of true individuality wasn’t wearing black t-shirts inscribed with such witty quips as ‘fuck it all’ (I know, it was a shock to me too) or which art a person consumes. But, instead, individuality develops from how a person responds to the art, plus how that response manifests itself and evolves within the individual.

Hayley Long – A Clockwork Orange

I was fifteen when I bought myself a copy of A Clockwork Orange from a local second-hand bookshop. I don’t know what made me pluck it from the shelf. Maybe it was the bright orange cover with that iconic stylised image of a man in a bowler hat. Maybe it was just the title. I’d heard of it and it was intriguing. But I had no guesses as to what story I might find inside. So I took a punt and bought it anyway. It cost me 50p. The price in my copy is fixed on the title page forever in pencil.

I must have frowned when I read those famous opening lines:

‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’

That was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie and Dim, Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry.

And, pretty quickly, a notepad and a pen appeared on my knee as I read. I know this because I remember my mum asking me what I was doing. ‘I’m reading a book,’ I guess I replied. ‘It’s written in its own made-up language. I’ve got to work it out.’

And that necessary extra little bit of effort was the book’s beauty and is what makes it so unforgettable. My ageing edition had no glossary in the back. In order to make sense of Anthony Burgess’s tale of Alex and his droogs, I had to meet Burgess halfway. Besides reading and reacting, I had to apply my own logic to make this novel work. Sometimes meanings escaped me but I ploughed on anyway. Sometimes the conclusions I arrived at were so horrifying, I wasn’t sure if I’d made some dreadful mistake. It was as if I were hearing Alex’s confessions through a filter. And although they shocked me, I just couldn’t stop reading. I suppose I was excited by my discovery that, as a reader, I was as vital to this book as the writer. Without me – without my active participation – Alex’s story could not be understood.

And that necessary extra little bit of effort was the book’s beauty and is what makes it so unforgettable. My ageing edition had no glossary in the back. In order to make sense of Anthony Burgess’s tale of Alex and his droogs, I had to meet Burgess halfway. Besides reading and reacting, I had to apply my own logic to make this novel work. Sometimes meanings escaped me but I ploughed on anyway. Sometimes the conclusions I arrived at were so horrifying, I wasn’t sure if I’d made some dreadful mistake. It was as if I were hearing Alex’s confessions through a filter. And although they shocked me, I just couldn’t stop reading. I suppose I was excited by my discovery that, as a reader, I was as vital to this book as the writer. Without me – without my active participation – Alex’s story could not be understood.

And did I like that story? Not really. A Clockwork Orange is one of the most violent and disturbing books I’ve ever read. But it’s insistence that I do something, that I take part and decode, left me, aged 15, feeling enormously empowered and proud that I’d got in – that I’d made it through the filter. It was like I was one of the readers that Anthony Burgess was relying on. In September, my next novel for young adults is let loose in the world. Sophie Someone has no violence or horror and it has no Russian linguistic borrowings. And it isn’t A Clockwork Orange, of course! But it has a kind of Nadsat nonetheless. And if I can make a single reader feel something like the sense of achievement I found at fifteen, that’s horrorshow enough for me.

Elin Williams – The Mermaids Singing

Around this time in 2008, I received my A Level results. My results were good enough to secure my place at Cardiff University to study Literature. I’d already chickened out of studying creative writing at Birmingham University, but felt happier knowing that I’d be that little bit closer to home in Cardiff. When I told people about my choice of course, I was always met with the same phrase: “Say goodbye to your love of reading! You’ll never enjoy reading again.” Obviously this was not the case; the only bad habit I walked away with was a tendency to skim read (a habit which I am still trying to rectify four years later). It was in 2009, my second year at Cardiff, when I had a sort of re-awakening. I’d always had a fondness for the macabre (I kept my encyclopaedia of serial killers in a cupboard at home so Mary Ann Cotton or Jeffrey Dahmer couldn’t kill me in my sleep) so I leapt at the chance to study Crime Fiction for one of my modules.

The module was brief yet enjoyable. It ranged from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Thomas Harris, but it was the last book we studied which really impressed me. The book was Val McDermid’s The Mermaids Singing. The title of the book was taken from Eliot’s ‘Prufrock…’ which he had in turn taken from Donne, so obviously any literature lecturer would practically wet themselves in order to discuss it, but I didn’t find the lectures on it particularly enlightening. The novel was pure brilliance in itself. It didn’t require a lecture to understand or appreciate it. The novel opened up another path for me as a reader, one filled with what I have heard many wrongly call cheap thrills (although this could be taken in a literal sense; you can pick up some classic crime fiction for less than a quid online). People will argue that some Crime Writers are trashy, but any author who can hold your attention so intensely that you literally can’t put the book down until you find out who did what and why is a good writer for me. Not only is Val McDermid one of these writers, but she also has an astonishing ability to craft a modern Gothicism through her writing. Her grimy, gritty Scottish settings never fail to entice, but for me, it will always be The Mermaids Singing that holds a special significance.

The module was brief yet enjoyable. It ranged from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Thomas Harris, but it was the last book we studied which really impressed me. The book was Val McDermid’s The Mermaids Singing. The title of the book was taken from Eliot’s ‘Prufrock…’ which he had in turn taken from Donne, so obviously any literature lecturer would practically wet themselves in order to discuss it, but I didn’t find the lectures on it particularly enlightening. The novel was pure brilliance in itself. It didn’t require a lecture to understand or appreciate it. The novel opened up another path for me as a reader, one filled with what I have heard many wrongly call cheap thrills (although this could be taken in a literal sense; you can pick up some classic crime fiction for less than a quid online). People will argue that some Crime Writers are trashy, but any author who can hold your attention so intensely that you literally can’t put the book down until you find out who did what and why is a good writer for me. Not only is Val McDermid one of these writers, but she also has an astonishing ability to craft a modern Gothicism through her writing. Her grimy, gritty Scottish settings never fail to entice, but for me, it will always be The Mermaids Singing that holds a special significance.

As for what it did to me in my teenage (just) years, I will always have something to read, whether it be more McDermid, King or Harris, a crime novel is the easiest to pick up off the shelf and delve straight into. As I write this, I’m glancing at a new crime fiction book I received as a gift last week and I can’t tell you how much I need to go and finish it to find out ‘Whodunnit’?

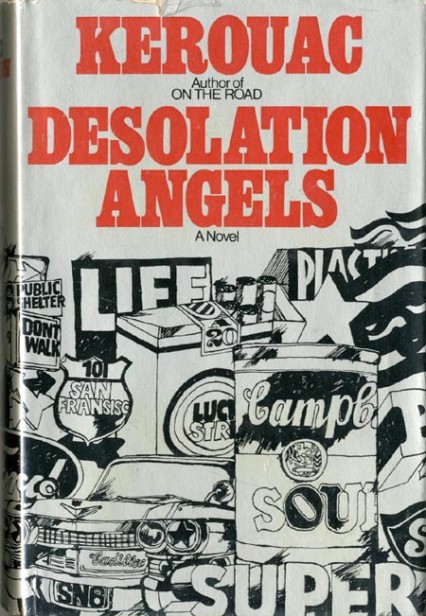

Gary Raymond – Desolation Angels

When I was sixteen I read Jack Kerouac – the best age to read Kerouac (and indeed I might argue the only age to read him). He was in literature the hero-type I had so often already had in cinema and music. He was a rock n roll star, in fact – in legend at least. It became clear as I delved deeper just what a complex and contradictory character Kerouac was. An excellent sportsman, driven to a wilderness by injury; a man who killed himself with drink, never really got a grip on life in the end, and who was riddled with the rot of his French Catholic upbringing. He invented the term ‘Beat’, and for all those who tried to add their own weight to the term with connotations of social struggle (Neal Cassidy and Allen Ginsberg both alluded to the label as a revolutionary one, the ‘beaten-down generation’ claiming their lives for themselves), it was Kerouac’s own explanation that was the most revealing, and the most beautifully sincere: that the feeling he had in those days was close to his understanding of Beatification. And this is why Kerouac was the real deal. He never quite fitted with the others, and that was because there was no pretentiousness to him. When he talked about Rimbaud he talked about someone he understood, not someone he strove to understand. Kerouac: conflict, Dostoevsky, sex, freedom. Kerouac was it. To me there was no Holy Trinity in the Beats; Ginsberg was just a druid and Burroughs a mad scientist. Kerouac was the working class loser with truth and beauty bursting from his soul. At 16 I read On the Road and then The Subterraneans, then Dharma Bums and Big Sur and Doctor Sax, and all I could think of was: this is the life within my grasp, a life that actually means something.

When I was sixteen I read Jack Kerouac – the best age to read Kerouac (and indeed I might argue the only age to read him). He was in literature the hero-type I had so often already had in cinema and music. He was a rock n roll star, in fact – in legend at least. It became clear as I delved deeper just what a complex and contradictory character Kerouac was. An excellent sportsman, driven to a wilderness by injury; a man who killed himself with drink, never really got a grip on life in the end, and who was riddled with the rot of his French Catholic upbringing. He invented the term ‘Beat’, and for all those who tried to add their own weight to the term with connotations of social struggle (Neal Cassidy and Allen Ginsberg both alluded to the label as a revolutionary one, the ‘beaten-down generation’ claiming their lives for themselves), it was Kerouac’s own explanation that was the most revealing, and the most beautifully sincere: that the feeling he had in those days was close to his understanding of Beatification. And this is why Kerouac was the real deal. He never quite fitted with the others, and that was because there was no pretentiousness to him. When he talked about Rimbaud he talked about someone he understood, not someone he strove to understand. Kerouac: conflict, Dostoevsky, sex, freedom. Kerouac was it. To me there was no Holy Trinity in the Beats; Ginsberg was just a druid and Burroughs a mad scientist. Kerouac was the working class loser with truth and beauty bursting from his soul. At 16 I read On the Road and then The Subterraneans, then Dharma Bums and Big Sur and Doctor Sax, and all I could think of was: this is the life within my grasp, a life that actually means something.

It may have been a con. Or perhaps I have only ever been right once in my life, and it was then. But Kerouac is responsible for making me want to be a writer. I wrote like him for years – awful drivel. I don’t admire his writing at all now – I ended up graduating to an admiration of great craftsmen rather than Benzedrine magicians – but you look back and he had blood in his veins; such a rarity in writers.

I can pinpoint the most significant moments of my teenage years to Kerouac, most notably running off to explore America when I was 18, dropped out of University after four months, with nothing but $200 in my pocket and… if you’ll excuse the cliche… a guitar across my back. But it wasn’t On the Road or Dharma Bums that I took with me; it was a battered old copy of Desolation Angels, perhaps his most elegiac and mystical of books. It is essentially two books, and it was the first that changed everything for me. In Part One, Kerouac (Jack Duluoz as he is here) is a fire watcher in Big Sur National Park in Southern California, and for 250 pages the reader is in his solitary company. Kerouac is alone for six months, he muses on man’s connection to nature, he creates fantasy baseball leagues, he remembers his childhood, he stares out across the treetops like Buddha to the abyss. The writing was like lava flow. And Desolation Angels – has to be one of the great titles of any work of art ever. I can’t quote from it. I can’t confirm details. I will never go back to it. It is there to remembered in a sepia fog, like everything else from back then.

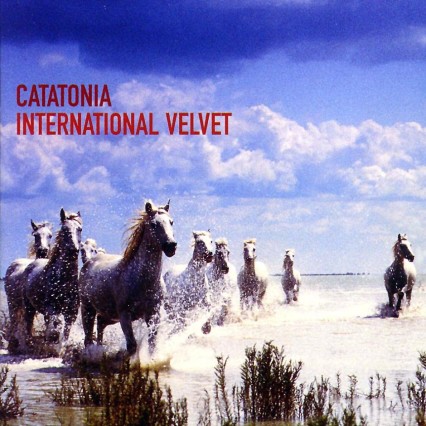

Sara Roshlyn Moore – International Velvet

In the early nineties Welsh things were not cool, I would turn my nose up at reading a Welsh book, would never confess to watching S4C and the Eisteddfod was where the swot’s and Welsh snobs went. Then came Cwl Cymru. The lyrics by the Manic Street Preachers’ ‘If You Tolerate This Then Your Children Will Be Next’ haunts me to this day.

The lyrics of International Velvet by Catatonia,

Deffrwch Cymru cysglyd gwlad y gan, dwfn yw’r gwendid bychan yw y fflam.

A rough translation;

Wake up sleepy Wales land of song, dense is our weakness small is our flame.

An instance awakening, it enthused my small flame. I suddenly felt Wales was a bigger part of the world, it broadened my mind and I was now proud to be proud. This newfound confidence made me happy, gave me hope and ambition.

An instance awakening, it enthused my small flame. I suddenly felt Wales was a bigger part of the world, it broadened my mind and I was now proud to be proud. This newfound confidence made me happy, gave me hope and ambition.

This along with the opening of the Millennium Stadium solidified this perception of a strong confident Welsh present within my psyche. I can always experience, feel and express my proudness of my land and language comfortably during rugby matches; so dodging Art Collage to visit the pub and witnessing the opening live at Cardiff was totally acceptable in my opinion. In 2008 a group of us travelled to Cardiff to a rugby match, during our journey I requested a song on Radio Cymru to soundtrack our adventure and they chose International Velvet for us!

A few months later I moved to Cardiff and worked at the Millennium Stadium for every rugby match. The best job I’ve ever had! These experiences have evidently become a huge part of me, I have recently graduated with an M.A in Fine Art, my goal through my art is to continue the happiness hope and ambitions of the Welsh.

Jane Roberts – The Decameron

From the age of eight till sixteen, I did not attend a conventional school: I was home-educated, taught by my parents. It can be dangerous to remove barriers, to do something a little revolutionary; and simultaneously rather exhilarating. During that time, I also learnt to educate myself. I read everything a school kid shouldn’t, watched films regardless of rating guidelines, and so on. I was a rebel. Well, a rebel geek.

A find one day in a room when I should have been learning…something else: a wooden box of old books from an auction. Heaven. Two large books with tatty brown paper coverings. Why the brown paper? The books seemed innocuous enough; yet they screamed of delicious censorship, they willed me to peel back the paper and read them. So I did. Foxed pages – edges discoloured and well-worn by so many eager thumbs and fingers. The intoxicating smell of must. The crackle of the tracing paper shielding the slightly erotic etched illustrations. Or at least a tame Victorian interpretation of erotica. The film of residue from the pages stuck to my fingertips, an invisible imprint of illicit activity. I had a secret.

A find one day in a room when I should have been learning…something else: a wooden box of old books from an auction. Heaven. Two large books with tatty brown paper coverings. Why the brown paper? The books seemed innocuous enough; yet they screamed of delicious censorship, they willed me to peel back the paper and read them. So I did. Foxed pages – edges discoloured and well-worn by so many eager thumbs and fingers. The intoxicating smell of must. The crackle of the tracing paper shielding the slightly erotic etched illustrations. Or at least a tame Victorian interpretation of erotica. The film of residue from the pages stuck to my fingertips, an invisible imprint of illicit activity. I had a secret.

I would learn about short stories, the novella, the processes of linking ideas and forming characters, and the art of engaging a reader. I would not realise how much this would go on to affect my later studies in Latin and Greek (in the same vein I can recommend Apuleius’ Golden Ass and Petronius’ (and Fellini’s) Satyricon), but also my love of writing. I’m still not 100% conventional, and I would encourage anyone to read past a mere school syllabus, and certainly to uncover those gems lurking behind censorious barriers.

Underneath those brown paper sheaths? Boccaccio’s Decameron.

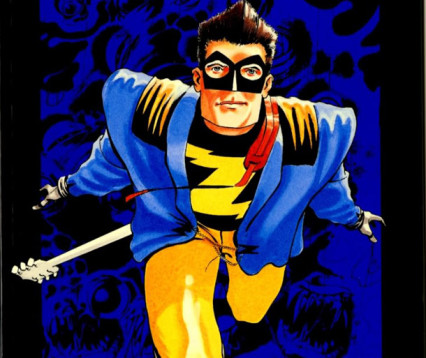

Matthew Mathias – Zenith

It was always comics for me. I was a late comer to music in my teens; actually I was a late comer to everything in my teens. While every boy my age seemed obsessed with music, clothes and girls, I just didn’t see the point. Clothes? Well, once I had my suede shoes, skin tight stone washed jeans and a thin white leather tie, I didn’t really need to think of anything more in that category. Girls? They were a huge mystery and a hindrance; and as for music, I couldn’t quite get into my head why, just because I liked one song by Duran Duran, Def Leppard or Terence Trent D’Arby I had to be obsessed by everything else they did.

After years of the Beano, 2000AD was the comic that would lead me into adulthood. This was my first vision of a future for an adult that could like comics! These stories featured warped visions of the future, sex, apocalyptic wars, berserker Celtic warriors, vampires before they become cool, it had everything. Then, in 1987 when I was 14 it had Zenith. Zenith was a British superhero created by Grant Morrison, Brendan McCarthy and Steve Yeowell. He wasn’t dark like Batman or a square-chinned hero a la Cap America; this was a superhero for the 80s, for Thatcher’s Britain. He was a vain, spoiled, selfish git who used his powers for himself and I loved him. Zenith’s Britain was very similar, but not the same as the one I inhabited. In his world the nuclear bomb had been dropped on Berlin. The war had seen the creation of a superhuman programme who growing up in the 60s had rebelled against the Government who created them, becoming ‘Cloud 9’. By the time the 80s had arrived all of them had supposedly lost their powers, some had died, one (the Welsh one) had become a drunk, one had become a Tory minister and two had children, Robert McDowell or Zenith. Although over the years the series became a bit batshit bananas, the initial impact was enough for me to fall for it hook, line and sinker. It led me to devour other novels, graphic and generic. It helped me search for writers that didn’t just write nice stories; I found ones that wrote FOR me. In Zenith, I loved the warping of 40s, 60s and 80s Britain and its new vision for a superhero ‘realism’ really showed its difference to anything that had come before it. I think Morrison said it all when he stated he intended Zenith ‘to be as dumb, sexy, and disposable as an eighties pop single…’ it really was…it still is…now where did I store my old Def Leppard tape?

After years of the Beano, 2000AD was the comic that would lead me into adulthood. This was my first vision of a future for an adult that could like comics! These stories featured warped visions of the future, sex, apocalyptic wars, berserker Celtic warriors, vampires before they become cool, it had everything. Then, in 1987 when I was 14 it had Zenith. Zenith was a British superhero created by Grant Morrison, Brendan McCarthy and Steve Yeowell. He wasn’t dark like Batman or a square-chinned hero a la Cap America; this was a superhero for the 80s, for Thatcher’s Britain. He was a vain, spoiled, selfish git who used his powers for himself and I loved him. Zenith’s Britain was very similar, but not the same as the one I inhabited. In his world the nuclear bomb had been dropped on Berlin. The war had seen the creation of a superhuman programme who growing up in the 60s had rebelled against the Government who created them, becoming ‘Cloud 9’. By the time the 80s had arrived all of them had supposedly lost their powers, some had died, one (the Welsh one) had become a drunk, one had become a Tory minister and two had children, Robert McDowell or Zenith. Although over the years the series became a bit batshit bananas, the initial impact was enough for me to fall for it hook, line and sinker. It led me to devour other novels, graphic and generic. It helped me search for writers that didn’t just write nice stories; I found ones that wrote FOR me. In Zenith, I loved the warping of 40s, 60s and 80s Britain and its new vision for a superhero ‘realism’ really showed its difference to anything that had come before it. I think Morrison said it all when he stated he intended Zenith ‘to be as dumb, sexy, and disposable as an eighties pop single…’ it really was…it still is…now where did I store my old Def Leppard tape?

Peter Reynolds – Tannhäuser

One cloudy December afternoon, ostensibly unwell and away from school, I aimlessly tuned into a broadcast of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser on BBC Radio 3. I was fifteen and had been casually reading about Wagner, but nothing prepared me for the impact of what I heard. I listened to the full three or more hours, but what hit me between the eyes was the overture itself – not the original overture, written in 1845, but the revised version Wagner made for Paris in 1861. In terms of its level of dissonance and frenzy, it marks an extreme point in his music; for me it opened up a world of musical intensity I had never previously experienced. Within weeks I took up formal musical studies leading to a degree and, later, a career in music.

One cloudy December afternoon, ostensibly unwell and away from school, I aimlessly tuned into a broadcast of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser on BBC Radio 3. I was fifteen and had been casually reading about Wagner, but nothing prepared me for the impact of what I heard. I listened to the full three or more hours, but what hit me between the eyes was the overture itself – not the original overture, written in 1845, but the revised version Wagner made for Paris in 1861. In terms of its level of dissonance and frenzy, it marks an extreme point in his music; for me it opened up a world of musical intensity I had never previously experienced. Within weeks I took up formal musical studies leading to a degree and, later, a career in music.

I can think of many things, forty years on, I would rather admit to in terms of a seismic teenage experience. Today Tannhäuser seems to me the least satisfactory of Wagner’s mature works: its scenario of the medieval minstrel Tannhäuser, his struggle between sensual and spiritual love and his eventual redemption by a pardon from Rome, makes my flesh creep. The music only intermittently rises to the magnificence of Wagner’s later achievements and the section that so transfixed me now seems hysterical and banal. But it opened doors for me and provided a experience one only encounters two or three times in a lifetime.

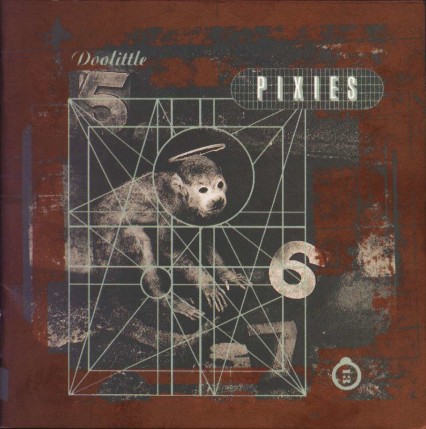

Gray Taylor – Doolittle

I was bordering on my teenage years in 1989. I was eleven, just in comprehensive school, with a great love of music but primarily I listened to music of previous generations. My parents had stopped listening to popular contemporary music in about 1965, so I educated myself and, finally, after making my way with a judicious chronology to the seventies, I found my ultimate hero: David Bowie. Thank whatever deity you subscribe to I did, for otherwise I would have lingered in a faceless limbo amongst a collection of ‘cool’ teens who professed that ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ was a Candy Flip song. For it was David Bowie who, just when I needed him to, came forth with advice on the best new band around.

Bowie had always been superb for finding out about other artists; he has always been a great champion of other people’s music. Via him I was already listening to Scott Walker, Lou Reed, Iggy Pop and the Stooges, Velvet Underground, Devo, Roxy Music, Kraftwerk, Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, and Prokofiev to name just a few. But, how would any of that translate into the cut throat, egomaniacal world that is teenageland? A place where your whole world can be turned upside down by not knowing the members of East 17, not liking rugby, or reading a book. A cruel, cold landscape of crap narcissism, crap haircuts, crap half adults fishing in an empty tank, empty ideas, empty sexuality, and a burgeoning sense that some would grow up to be toothless civil servants, whilst others would grow up to become big bully boy success lawyers, raping goodness from everything. How to hold your own here?

Bowie himself was experiencing a weird kind of second teenage period in his early forties, fed up of pop success, he had thrown a massive teenage strop and formed a band called Tin Machine around him like acne on a teenage boy’s face. They were an attempt to rid himself of his pop audience and came forth with a dreadful garage rhythm section, one draft lyrics, and a squalling guitar sound sure to scare off the ‘Let’s Dance’ fans. But, along with this new, alternative rock Bowie came the recommendations I needed to survive. OK so I was not going to make any friends by discovering Steve Reich. But then, on Antoine de Caunes’ seminal music show Rapido, Bowie was showing off his new band, but with typical generosity and a good dose of understanding how to manipulate acceptance for his new band, he was also talking about two other groups: Dinosaur Jnr and Pixies.

Bowie himself was experiencing a weird kind of second teenage period in his early forties, fed up of pop success, he had thrown a massive teenage strop and formed a band called Tin Machine around him like acne on a teenage boy’s face. They were an attempt to rid himself of his pop audience and came forth with a dreadful garage rhythm section, one draft lyrics, and a squalling guitar sound sure to scare off the ‘Let’s Dance’ fans. But, along with this new, alternative rock Bowie came the recommendations I needed to survive. OK so I was not going to make any friends by discovering Steve Reich. But then, on Antoine de Caunes’ seminal music show Rapido, Bowie was showing off his new band, but with typical generosity and a good dose of understanding how to manipulate acceptance for his new band, he was also talking about two other groups: Dinosaur Jnr and Pixies.

Dinosaur Jnr would be one of the bands I discovered the joys of slowly, but it was Pixies that captured my imagination completely. Their new album was called Doolittle, and thankfully because I’m not sure my eleven year old head could have made sense of the angular, Steve Albini-produced previous album Surfer Rosa. The weekend after I saw the show I raced to the recently opened Diverse Music in Newport town centre. Flicked through the ‘P’ section and there it was. I didn’t have a CD player until many years later, so we are talking about vinyl. The LP cover looked amazing; bronze and brown, semi-gold, a vague picture of a monkey. No picture of the band. The inside art work, (completely lost on the recent anniversary reissue), contained pictures of blood-covered maritime rope and severed dolls heads. No pictures of the band. The song titles were strange and obtuse; ‘Wave of mutilation’, ‘Dead’, ‘I Bleed’, were not song titles Stock, Aitken and Waterman were going to come up with and still they gave no picture of the band.

When I got my new purchase home, I went straight to my room, there had been no snippet of Pixies music on the TV show, so I was completely unaware of what I might hear as my stylus touched the vinyl for the first time. When it did my life changed. The bass line of opening track ‘Debaser’ seemed smooth, unlike the garage sludge of Tin Machine, I checked the band credits, it’s a female bassist. The guitars clashed over the top of the bass in a way I had never heard, the guitarist’s name seems spanish. The singer’s name was written as Black Francis and when his screaming, insanity pitched vocals matched this name. I had never heard a singer like it. A scream so pure. Lyrics impenetrable to the point they make sense. Pixies? These musicians must be as they sound; small, vicious, sharp toothed, Nosferatu finger nails, more shadows than people, fully formed creatures under the bed, the cast of Clive Barker’s Nightbreed. Of course, when they finally became famous, the members of the band were disappointing in their normality. But, for this moment they were horror super heroes.

Every single track washed over me like a punk baptism. This was not punk but I felt the energy of punk, of David Lynch, of Hieronymous Bosch, of The White Album, of video nasties, of pure pop glory. It is hard for me to break the album up into tracks, because this album has no low point, it is a perfect collection in just the same way a Picasso is the perfect collection of brush strokes. Rather than any recommendations of individual tracks, I urge you to hear this masterpiece as a whole, complete work of art.

Because of Doolittle by Pixies, and because of Bowie, this teenage boy had discovered real cool. I knew that I was right, that the throwaway pop music I was peer-pressured toward liking, but resisted, was shit. I knew that this music would last with me forever and because of it I gravitated to likewise minds and people, many of which are still very close friends today. The album led me down an alternative rock route that opened the door to Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Husker Du, Sugar, and so many more. If David Bowie had never made an album it would be my favourite album of all time and it saved my teenage years completely.

Phil Morris – Pirandello’s Henry IV

I was sixteen and planning a career in politics, a more shameful admission of my teenage years than a nascent drug habit and clumsy sexual fumblings I’ll concede – but I attended local Labour Party meetings, listening to heated debates on the naming of roundabouts and condemnations of apartheid South Africa by Newport-West GMC. This waking nightmare of tabled amendments and demands to yield the floor was shattered not by the House-inflected beats of The Stone Roses, nor the mind-expanding properties of Ecstasy, but a play by Luigi Pirandello.

I was sixteen and planning a career in politics, a more shameful admission of my teenage years than a nascent drug habit and clumsy sexual fumblings I’ll concede – but I attended local Labour Party meetings, listening to heated debates on the naming of roundabouts and condemnations of apartheid South Africa by Newport-West GMC. This waking nightmare of tabled amendments and demands to yield the floor was shattered not by the House-inflected beats of The Stone Roses, nor the mind-expanding properties of Ecstasy, but a play by Luigi Pirandello.

A production of Pirandello’s Henry IV was headed to the West-End, trailing a wake of fired directors, set designers and cast-members. Blame for this chaos was laid at the door of its star, Hollywood has-been Richard Harris. Rumour was that the old hell-raiser was creating hell for his creative team with his amateur scholarship on this modernist classic. I saw the play with my parents, for whom Harris was a touchstone of 60s rebellion, and almost cried with laughter at his initial gurning and gesturing, which would have embarrassed Donald Wolfit.

The protagonist of the play is an Italian aristocrat who injured his head in a fall, while playing the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV in a historical pageant. Waking to the delusion that he is the actual German medieval monarch, he has spent the past twenty years holding court in an elaborate set-dressed villa – an elaborate stage-fantasy staffed by actors hired by his wealthy nephew.

Harris beautifully crystallised the key moment of the play, whereby Henry reveals to these actors that he has been sane for the past eight years, and merely playing along with the elaborate charade. In one electric moment, which I’ll never forget, Harris wearily removed his ridiculous straw-blonde wig and sighed, “I’ve got a bit bloody bored with all this.” He appeared to slip out of character – was this Harris or Henry speaking? There followed a discussion on the subjectivity of reality, in which Henry explained that he was sane because he was fully aware that he wore the mask of Henry IV, while others wore masks but were unaware that they did so. This may sound like cerebral intellectualising but Harris made it seem directed to the vital question of what it is to be human.

Harris had played with his well-earned reputation for over-acting and bad-boy behaviour to reinforce the shock of his meta-theatrical shift from acting to being. In doing so, he had shown me that there existed a public forum, outside of politics, in which ideas about life and its purpose could be explored with real urgency and to their fullest extent. After that performance I would devote myself to theatre and not the Labour Party. This was in 1990. I cannot thank Harris enough.

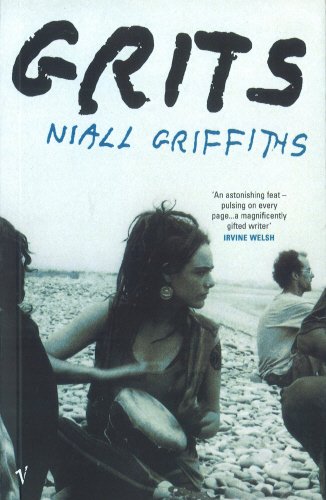

Rhys Milsom – Grits

I first picked up Grits in a charity shop. Back then, I’d never heard of Niall Griffiths even though Bukowski, Welsh, Niven, Selby Jr and Martin Amis were squabbling over who should be read next. There was something about the cover of Grits that drew me instantly to it. Whether it was the hazy, bold font of the title or the enigmatic black-and-white image of a group of people sat on a rocky beach remains a question. But, pick it up I did and buy it I did.

I first picked up Grits in a charity shop. Back then, I’d never heard of Niall Griffiths even though Bukowski, Welsh, Niven, Selby Jr and Martin Amis were squabbling over who should be read next. There was something about the cover of Grits that drew me instantly to it. Whether it was the hazy, bold font of the title or the enigmatic black-and-white image of a group of people sat on a rocky beach remains a question. But, pick it up I did and buy it I did.

Flicking through the book at home, I realised that this copy had actually been signed by Niall Griffiths. Why the original owner gave it away, I’ll never know. But, the fact that Griffiths’ signature was there, on the first page, led me to instantly start reading. It felt real, genuine, like this copy had purposely made itself known to me. And the same went for the writing.

The opening, including this: ‘They are moving through these green and desolate hills…’ was one of the strongest introductions to a novel I had – and, to this day, still have – come across. I remember thinking, who are ‘they’? Why are the hills juxtaposing themselves – ‘green and desolate’? The way Griffiths wrote so informally, yet still managed to clasp your eyes to the pages, turning and turning, was extraordinary.

His use of colloquial language, the subtle techniques in plot and structure, the intriguing yet (sometimes) abhorrent characters had me fixed. So much so, that I now own everything he’s released. Grits – and Griffiths – showed me that with writing, there are no rules. In fact, you make your own. I should be brave. Grits played a massive part in the writing style I’ve developed now, and without it I firmly believe I’d never have had the confidence to write in my own style and send pieces off for publication. Without it, I definitely wouldn’t be writing this. Go and pick it up.

Emily Garside – What the Night is For

The play that changed my life was a play about adultery. I was 15. Luckily in this case it was the medium not the message that changed me powerfully (though I may have picked up some tips on catching a cheating spouse) The play was What the Night is For by Michael Weller. Directed by esteemed director John Caird and starring acting wonderful classical actor Roger Allam. At 15 I knew none of this; I begged to make the trip from Cardiff to London because I wanted to see Gillian Anderson on stage.

The play that changed my life was a play about adultery. I was 15. Luckily in this case it was the medium not the message that changed me powerfully (though I may have picked up some tips on catching a cheating spouse) The play was What the Night is For by Michael Weller. Directed by esteemed director John Caird and starring acting wonderful classical actor Roger Allam. At 15 I knew none of this; I begged to make the trip from Cardiff to London because I wanted to see Gillian Anderson on stage.

I’ve seen plays since that have had more emotional impact, that have changed me as a person or the way I see the world. But this play gave me more: it gave me theatre.

My copy of the script is covered with notes, furiously scribbled on the way home, about the staging, the lighting, the costumes, anything so that I could capture those moments. I actually needed have bothered because it’s burned into my mind. It wasn’t in fact that this play did anything particularly special, more at that point I had no concept of what theatre was, what it could do. The play wasn’t effects laden, it wasn’t complicated, it was two people on stage, telling a story. And that was the spark of magic for me.

Years later I can’t articulate what it was that hit me so powerfully, other than the obvious: it was there, it was live, it was real. I can say what that moment, as an impressionable teenager did (again nothing to do with adultery) Theatre has given me my professional drive. It took me to drama school and this year I got my PhD in drama. I sometimes marvel that I’m classed as some kind of ‘expert’ in a field I only stumbled into because I was a teenager who loved Gillian Anderson.

You can join in the discussion with Wales Arts Review on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram using the #TeenageKicks hashtag.

Original illustration by Dean Lewis