Cardiff Festival of Voice, Weston Studio and Rehearsal Room 3, Wales Millennium Centre, 9 June 2016

The Last Mermaid (Festival of Voice Commission)

Music: Charlotte Church and Siôn Trefor

Words: Charlotte Church and Jonathan Powell

Director: Bruce Guthrie

Opera for the Unknown Woman (world premiere)

Written, directed and co-composed by Melanie Wilson

Co-composed by Katarina Glowicka

A Fuel Theatre Production

Opera and musical theatre have long been potent vehicles for political and social commentary. From the French Revolution values of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and Beethoven’s Fidelio, to the biting satire of Weill’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and Nono’s Marxist-fuelled Intolleranza, many composers have raised a voice on behalf of change or in protest at the iniquities they’ve seen around them. No surprise then, that contemporary composers should want to do the same – and that they should be turning to issues of climate change and the oppression of women; two of today’s most urgent world-wide challenges.

On June 9, the Wales Millennium Centre hosted a pair of very different works which shared common cause in the first of those issues. The Last Mermaid and Opera for the Unknown Woman are both ‘last survivor’ tales and both seek ultimately to find hope in the face of a bleak future; the first is a show largely aimed at children, and the second steps into gender politics in exhorting women to rise up and act on behalf of themselves and humanity. With varying degrees of success, both pieces utilise elements of opera, movement or dance, choral singing, recorded sound and video to get their message across.

Charlotte Church’s The Last Mermaid (co-written with Jonathan Powell and Siôn Trefor) proved a heartfelt statement from a singer who knows all-too well the vitriol that can greet women in public life who dare to offer opinions. That she has not only survived the transition from media-darling child star to media-reviled political campaigner, but continues to reinvent herself creatively, is impressive indeed. Here she pours her considerable passion – without a trace of bitterness – into a dark adaptation of Hans Christian Anderson’s story of self-sacrifice and redemption, The Little Mermaid. Walt Disney this is not – thank God. But nor is it devoid of misfires; not least in that the narrative gets swamped in a succession of musical numbers involving a plethora of dancers and singers whose role is sometimes unclear, and whose words are often inaudible.

Yet there was much to engage the kids and adults entranced alike by the bubbling, video-rich spectacle created by director Bruce Guthrie and team. To a score which straddles with ease floaty neo-Enya and metronomic techno, Church – the eponymous mermaid – is born. Her world is all blue-green shimmer of ‘tender waves’, wafting sea creatures and drifting plastic bags which pollute the ocean: hence she is the last of her kind. She saves a drowning man and is inspired to follow him onto dry land by a gender-neutral whale (a duo of presumably ‘feminine’ countertenor and ‘masculine’ baritone, well-intentioned but a bit suspect in the typecasting). There she meets the future in the form of a beguiling little girl, but falls sick and returns to the sea. Along the way, in one of the most striking and colourful sequences of the evening, she encounters a neon-clad army of commuters who, with echoes of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, are addicted to the ‘medicine’ that proves so toxic to she herself.

It’s a great conceit that needs refining in practice, but that manages to skirt just the right side of modern-day ‘thou shalts’ in subverting Anderson’s moralisng, 19th century tale. There’s a trick or two missed; for instance, like the original, it’s a man who prompts the mermaid to give up her watery abode, in a classic case of female self-sacrifice for impossible love. And the ending needs to do more to viscerally engage, or risk appearing to go through the new-age e-motions, so to speak. But I’d wager that the ultimate message – that ‘the power within can change everything’, if only we listen and take responsibility – is delivered with enough un-patronising energy and musical verve to hit home with at least some of the youngsters present.

***

There’s no shortage of fervour behind Melanie Wilson and Katarina Glowicka’s Opera for the Unknown Woman, which has some effective sequences within a potentially gripping concept. But the work is let down by a lack of energy in the direction and a didactic tone. Wilson has described the piece as a ‘science fiction opera about women saving the human race from the effects of climate change’. A fascinating idea, and reminiscent – to me, at least – of a kind of coming together of Doris Lessing’s feminist The Golden Notebook (albeit she derided the label) and her subsequent series of ‘space fiction’ novels, Canopus in Argos: Archives. Wilson’s credentials are impressive, having worked with the superb director Katie Mitchell, for instance, as sound designer on a number of productions. But her concept here lacks three-dimensionality in performance, precisely because it comes across as a concept, rather than realising the underlying emotional power in a way necessary to bring such ideas alive.

The title appears to reference Aaron Copland’s 1942 Fanfare for the Common Man (made famous by Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s 1977 cover), and especially brings to mind American composer Joan Towers’ feminist riff on that title, Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman (1987 revised 1997), performed at the BBC Proms in 2012. Of course the point is that, too often, ‘man’ is the default descriptor for ‘humanity’, and women become adjuncts or far worse – abused or kept in poverty and servitude. As the piece reminds us over and over again, it is women who pay the heaviest price for (men’s) impulses towards violence, rape and planetary conquest; the risk, at this point in human history, is that patriarchal addiction to ‘oil and money’ threatens to destroy all of us along with the earth itself.

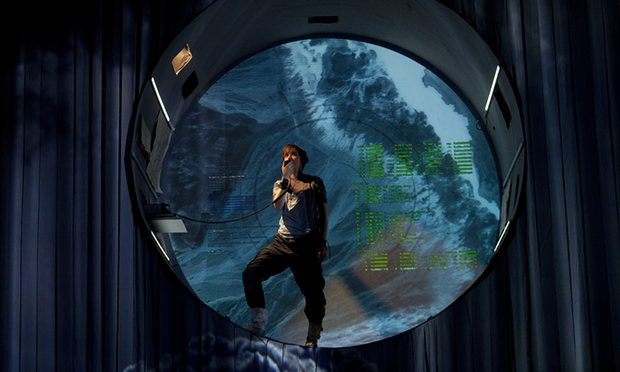

The setting alternates a doomsday scenario 300 hundred years hence with the present day. Earth lies devastated and the only hope for humanity is Aphra, the last woman left alive – but she has only two weeks to live. A total eclipse of the sun morphs into Aphra’s weather station sanctuary above the stage. This looks down, amid televisual projections of changing weather patterns and photos of real-life women protestors, onto a group of present-day women of many nationalities. These ten singers/speakers – three of whom double at different times on percussion, violin and cello – have been brought together at the behest of a council of human-looking alien women, depicted in striking, vocoder-rich sound and video projections onto the semi-circular backdrop. The earth women are exhorted to act now, before it’s too late and the threatened apocalyptic future becomes reality.

Various doom-laden announcements are intoned: ‘our own end-times are upon us’; ‘the future is an unknown woman waiting for death’; ‘your silence will not protect you’. The women respond by discussing their predicament: that, in Africa, seeds need to be given into the hands of female farmers; that they will be attacked for speaking out; and more vociferously, should they enact violent reprisal for the ills visited on them by patriarchy? The inference is that in some way all women are unknown – to ourselves as much as to each other and the world at large – and that it is only by stepping into our power as individuals and en masse that we can act to prevent social and climactic catastrophe.

This is all great in theory – and kudos to Wilson and her team for the well-chosen all-women cast, which features such excellent singers as Kate Huggett (Aphra), Patricia Rozario and Adey Grummet. But the piece veers dangerously towards racial stereotypes in its gathering of women representatives of cultures from each continent. This is not helped musically by the predictable harmonic minor swerves in the ‘Middle Eastern’ music, for example, which accompanies the Tunisian artist. More effective is the dissonant choral writing and less generic folk styles, whilst the interplay of live and recorded sound works well.

Ultimately, the piece is laudable in its intent to awaken us to vitally important socio-political and environmental issues. But I suspect Doris Lessing came to mind partly because it provoked memories of ‘80s and ‘90s identity politics: the women’s consciousness-raising groups and social activism which too often became bogged down in endless, self-referential debate and bickering over terminology. Ironically, this is a scenario that current fourth-wave feminists and social campaigners risk repeating – especially regarding transgender issues. Alas, the problem remains: how do you debate areas of controversy that are crying out for revolutionary change in a way which enables all voices to be heard, but without losing sight of the bigger picture?

In Wilson’s opera, while the production is handsome and the manifesto sound, there’s just too much head to engage the heart, despite the hopeful ending. Nevertheless, art is nothing without risk and experimentation, and Cardiff Festival of Voice deserve praise for hosting the world premiere of ‘Unknown Woman, and for commissioning ‘Mermaid: two completely contrasting yet oddly not dissimilar, thought-provoking works.

Header photo Kirsten McTernan