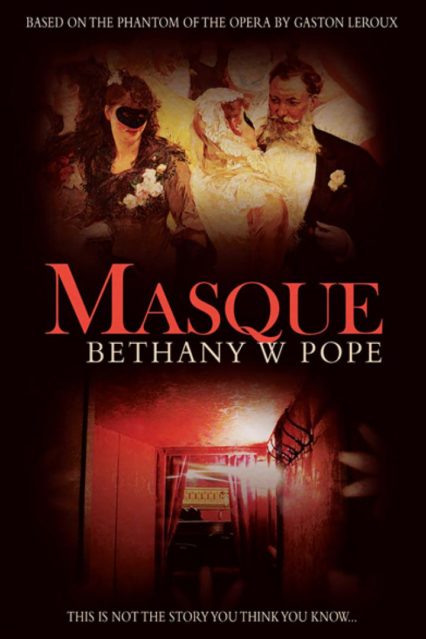

Bethany W Pope’s novel, Masque, carries the intriguing strap line: ‘This is not the story you think you know…’. I would hazard a guess that most of us are familiar with the plot of Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera: the beautiful young opera singer Christine is in love with the handsome and wealthy Raoul, while the monstrous, murderous Phantom, her singing master and platonic father figure, does his best to thwart that love and keep her for himself. He is her dark side, and Raoul her light. Neatly, but unsatisfyingly, he finally concludes that he is not worthy of her love and frees her. He dies, and she (one assumes) lives happily ever after.

From the first page, Pope begins her inversion of the original. Here, Christine is a mature woman with greying hair and decades of regret behind her. Though she lives a safe and comfortable life, a prima donna who commands respect, she experiences the world around her through an internal filter of perceived threat and darkness. The girl who brings her gifts is a ‘ballerina rat’ who she imagines feeding on her blood if given the chance. Her own faded reflection in the warped mirror shows a face that ‘might belong to a skull, scraped to bone’. Yearning and loss invade Christine’s present and ready the reader for her version of the past.

From the first page, Pope begins her inversion of the original. Here, Christine is a mature woman with greying hair and decades of regret behind her. Though she lives a safe and comfortable life, a prima donna who commands respect, she experiences the world around her through an internal filter of perceived threat and darkness. The girl who brings her gifts is a ‘ballerina rat’ who she imagines feeding on her blood if given the chance. Her own faded reflection in the warped mirror shows a face that ‘might belong to a skull, scraped to bone’. Yearning and loss invade Christine’s present and ready the reader for her version of the past.

The story moves swiftly between the three main characters: Christine, Erik (the Phantom), and Raoul. Each are given a handful of pages at a time, to recount their histories and detail their version of the unfolding drama, before passing the narrative onto the next character to carry the story forward. Each voice is distinctive and isolated from the others. Raoul experiences his connection with Christine through the exclusive framework of his pompous ego and narrow-mindedness, wholly oblivious to the possibility that she may not feel as honoured and enamoured as he assumes she must. Erik trembles before the force of his own deformity and his seemingly unrequited love for Christine, while her attraction to him, as a man rather than a singing master, does not transcend her sections of the book and plant itself in his awareness until it is nearly too late for them both.

Raoul is a figure of contempt through the narrative, despised by Christine. His inability to treasure her talent, her art, renders him totally unsympathetic and unlikeable. His love for her, while deep, is that of a spoiled child with a precious toy; she serves no role in his life and heart other than as a prized possession.

I remember the shape of her warm mouth as she spoke, twisting the sea-water out of the silk. I remember that her voice was silver. It did not matter what she said. To me, it was an invitation. I had earned her.

Raoul, with his utter lack of imagination or self-reflection, represents the safety of compromise and convention. He is in sharp contrast to Erik, who represents art itself and the risks and challenges a life devoted to art entail. Nothing, for Erik, should stand in the way of the act of creating. Even human life must be sacrificed if necessary, and without qualm.

Christine is no passive heroine waiting for love and male superiority to decide her fate. Single-minded and ruthless in her drive to place her art above all else, she is close to being an anti-heroine; deceiving her fiancé without a second’s thought or pity, allowing atrocities to take place around her without challenging them and with only brief concern. Not until the novel’s dramatic final stages, when she loses Erik and her art and allows herself to be caged into marriage with Raoul, is she humbled enough to fully appreciate the complexity of her urges: that there is as much to repulse as there is to attract, in both the life she chose and the life she didn’t.

It has got to the point that I feel like I am playing a parody of myself as I once was: the passionate, dark-haired post-adolescent who wanted nothing out of life but the freedom to sing. Well I finally have it. It comes at a cost.

The language and imagery through Masque is both sumptuous and unsettling. Masks appear again and again, in many forms. The reader is constantly reminded of a darker reality beneath the facade. The opera house is ‘built like a skull beneath the skin, ugly bones beneath some beautiful flesh’; Raoul worries that Christine is ‘brass overlaid with gold’; and the plush silken walls in Carlotta’s dressing room have been set with arsenic to render them a brilliant yellow.

Erik’s own mask hides a truly grotesque face, and Christine’s revulsion to his deformity is instinctive and visceral. Pope is unflinching in her descriptions of Erik; he is no frog to be kissed into handsome-prince-hood. If she is to truly love him then Christine must overcome her horror, and learn to embrace him as her lover. By the end of the novel, re-united with him once more, she attempts to do just that.

‘Teach me again, Erik. You taught me to sing, now teach me to look. I am a fast student. I am ready to work.’

With Masque‘s ending, Pope over-turns the moral lessons of Leroux’s original, where ugliness lives and dies in the darkness below ground and only beauty is permitted the light of day; she over-lays her own moral to this story: the transformation must be internal, for happiness to be achieved. Still hideous, still monstrous, the Phantom is physically unchanged but now accepting of his looks. His mask is set aside. Christine is the one who must undergo transformation and arrive at total acceptance in order to be complete.

The poignancy of this finale perfectly ends a novel richly layered with both gothic appeal and intellectual depth. In Masque Pope has initiated an important dialogue about the value of art to the human soul, and the psychological masks we wear as we pick our way through life.

Masque by Bethany W. Pope is available now from Seren, 220pp, £6.99