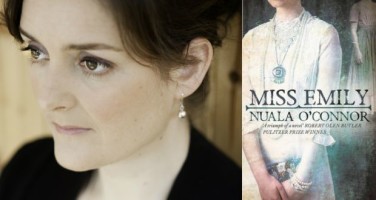

John Lavin reviews Miss Emily, award winning Irish writer and poet Nuala O’Connor’s third novel, exploring the life of Emily Dickinson.

Nuala O’Connor will be more recognisable to readers by the Irish spelling of her surname, Ní Chonchúir. This is the author’s third novel – and twelfth book in total – but her first as O’Connor and, as the Anglicisation might be expected to indicate, it represents something of a sea change in regard to her existing oeuvre. But while Miss Emily is a work of historical fiction, it would be a mistake to think that Nuala O’Connor/ Ní Chonchúir had moved away from any of the hallmarks of a prose style that has marked her out as one of the most consistently original Irish writers of the past ten years.

This is not entirely new territory, in any case. The author has dipped her toes into these waters occasionally in the past, most notably in the 2013 short story, ‘The Boy from Petropolis’, (concerning another poet, Elizabeth Bishop), an intriguing piece about the poet’s time in Brazil – something which may, perhaps, have encouraged the author to take on this larger and more complex piece of research.

For Miss Emily not only takes us into the world of Emily Dickinson and her household, it also, rather boldly, takes us directly into Emily Dickinson’s thoughts. Evidently, this is a difficult thing to achieve when writing about a historical figure widely held to be a poetic genius, and O’Connor tackles the problem in three ways. Firstly, by immersing herself in Dickinson’s poetry and letters, so that the book teems with minutiae about life in the poet’s Amherst home. Secondly, by not attempting to convey Dickinson’s speech and inner monologues with complete exactitude but rather in a poetic manner which is in keeping with the musicality of Dickinson’s verse. This works because O’Connor herself is an extremely adept and memorable wielder of poetic prose, so that while the reader may fleetingly think – Would Dickinson really have said that? – they don’t linger over the thought because of the memorable image that they have been presented with in its stead. Take this example, in which O’Connor captures both Dickinson’s ever-present poetic sensibility – that marvelous ‘suck-and-sump’ – while also giving us an insight into the geography of her mind:

Bundled up like an Alpinist, I trudge through the garden. Pleasing suck-and-sump noises rise from my feet. …I find a redpoll on a bush, chirping merrily to the sky.

‘You sit here singing and nobody can hear you. Why do you sing?’

He chirrups and cheeps, as if to say, ‘I live to sing.’ And so I am castigated by a red-capped, brown bird, browner – if it is possible – than my cloak.

Thirdly, O’Connor also takes us into the mind of another, fictional, character: Dickinson’s Irish maid, Ada Concannon.

It is this introduction of Concannon which really brings the book to life, allowing the author to not only show Dickinson from an alternative angle but, also, to write about a Nineteenth-Century Irish woman adapting to life in America – something that she does with aplomb. The narrative switches between the viewpoint of the two central protagonists, a device which facilitates plot and character development very successfully, while also giving ample opportunity for dramatic irony. O’Connor is excellent at showing each character’s particular quality of naivety, i.e. Ada has no inkling at all as to why Dickinson is furious with her when she walks in on the poet and her sister-in-law embracing after Christmas lunch (O’Connor hints at the poet’s sexual orientation with subtlety throughout the book). Meanwhile Dickinson, so often lost in her own worldview, is equally – at least, at first – uncomprehending of Ada’s blossoming romance with her fellow countryman, Daniel Byrne.

This relationship with Byrne and the terrible ordeal that Ada undergoes at the hands of the diabolical, alcoholic Crohan form the backbone of the plot, and if there is any complaint to level at this superb novel it is only that it is called Miss Emily rather than Miss Ada, because it is really Ada that is the heroine. Dickinson genuinely did have a confidant Irish maid, one Margaret Maher, but Ada is an invented relation of Maher’s, working for the Dickinson’s in the year before Maher arrived. It is an inspired idea on O’Connor’s part because it allows the novel to move outside the remit of the purely historical. One of O’Connor/ Ní Chonchúir’s primary subjects has always been the role of women in society – particularly in Irish society – and so it makes sense for the author to turn her eye to an Irish serving maid fleeing recently famine-torn nineteenth Ireland. Indeed Ada’s story begins in Dublin with the maid going against her father and her employer’s wishes and lowering herself ‘into the Liffey… [her] underclothes bloom[ing] like seed pods’, for a pre-work swim. Soon she is banished from the kitchen to work in the scullery, having been described as ‘a muddy-rat’, something which only compounds her determination to seek an alternative way of life. Much like a character in an O’Connor/ Ní Chonchúir short story, Ada is an independent Irish woman unsatisfied with the constraints placed on her by a class-based, inherently patriarchal society. She is a proto-feminist, in this sense, and she leaves for America imagining it to be a place of freedom and opportunity, as so many Irish people did, of course, in the aftermath of the potato famine. What she discovers there is a kind of emancipation in the friendship that she finds with her employer’s daughter, Emily Dickinson, a woman with little concern for the strictures of the class system. She also experiences a great deal of hardship, however, and O’Connor does not shirk from describing the physical and emotional suffering that a woman of Concannon’s social rank would have undergone had they found themselves in the desperate situation that Ada finds herself in.

Overall Miss Emily is the success that it is because it works on these different levels. It is a beautifully realised meditation on Dickinson and the creative process. It is also entirely successful viewed simply as a romantic literary page-turner of the highest order, and is certainly worth buying for this quality alone. But above all it is a poetic, socially conscious novel about female empowerment that has important things to say about how we, as human beings, treat one another.

Miss Emily is available from Sandstone Press.

Author Photo of Nuala O’Connor ©Emilia Krysztofiak

John Lavin is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.