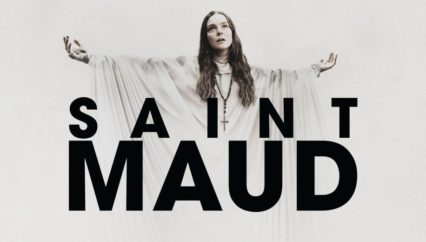

Rosie Couch reviews Saint Maud, a psychological horror starring Morfydd Clark as a private nurse whose growing obsession to save the soul of her terminally ill patient spirals out of control.

Saint Maud, Rose Glass’ directorial debut, tells the story of a private nurse appointed to take care of a former dancer, Amanda, who is dying of cancer. Initially, Maud’s characterisation and relationship to her surroundings allow a surprising undercurrent of relatability to pulse through the narrative. Maud is a young woman in an unfamiliar place, struggling to find her purpose. She is something of an outsider in the seaside town setting, the only Welsh person we encounter, and her existence feels lonely, precarious, and ex-centric.

Take away the flashbacks to a mysterious murderous incident and the subsequent episodes of violence, both replete with Maud’s bloodied hands, and Saint Maud starts to echo the trappings of your typical indie film – the type concerned with the loneliness of floating through existence unfulfilled, and the strain towards ‘proper’ adulthood where, apparently, you will know who you are and what you want from life, what life wants from you.

This familiarity skitters as the film unfolds, its pointed, sharp, atmosphere unrelenting throughout and reinforced by the seat-vibrating score. Caring for Amanda, Maud decides, is her purpose. Her duties, however, go beyond the bounds of palliative care. ‘It takes nothing special to mop up after the dying’, Maud muses, ‘but to save a soul, that’s quite something’. Awkward encounters with a former colleague reveal that Maud was once known as Katie. Said colleague is surprised to learn that Maud is still nursing, lending weight to the brutal flashbacks we witness. Something made Maud leave her previous position. The same bloodied something has made her turn to God. Her piety is new, associated with what seems to be a devotion to a non-denominational branch of Christianity.

We don’t see her go to church, or with fellow worshippers. A crucifix takes pride of place on the dank wall of her studio flat, looking down on Maud as she self-flagellates in inventive ways (one particular scene, and its associated crunches, will be hard to scrape from your mind). Such iconography, though admittedly with added extremity, suggests a leaning towards Catholicism. There is a sense that Maud is hurting herself in order to feel close to God, but also to repent for her previous actions.

Ultimately though, like William Blake – who is the subject of a book gifted to Maud by Amanda, and who was actively critical of organised religion – Maud is selective in her practices and carves her own religious space. This idea is further evident in her patron saint necklace, detailing Mary Magdalene. Patron of penitent sinners, converts to Christianity, sexual temptation, and people ridiculed for their piety, Mary Magdalene’s tenets align with Maud’s characterisation and the events of the film. When Amanda catches the necklace as it dangles from Maud’s chest during a physiotherapy session, Maud admits that she had to buy the necklace online rather than from any established church.

To say that the atmosphere of Saint Maud possesses, or shudders with, a brittle quality is less a comment on the narrative’s strength as a work of cinema, and more about how the filmic mood constructs and reflects Maud’s unstable psyche. There is a sense that violence could erupt at any moment, that the past could return and disrupt.

However, another key theme, or narrative disruption, in Saint Maud is a pleasure. In the aforementioned physiotherapy scene and beyond, Maud shows a palpable discomfort during interactions with those around her, and within her own body. The drabness of her life, at times, seems to reject the possibility of satisfaction through physical connection with others and the world around her. In contrast, Amanda does not stop pursuing pleasure during her period of receiving palliative care. She is persistent in her right to continue to socialise, drink, have sex, and smoke, however much she might please.

One question teetering around the film is whether Maud decides Amanda’s soul needs to be saved due to her actions as a whole, or whether the sight of Amanda having sex with another woman is the catalyst of Maud’s mission. Due to another memorable moment, this time in dialogue, I’m leaning towards the former – it seems that it is the sexual activity, rather than the partner’s gender, that is Maud’s problem. Either way, when dismissed by Amanda, Maud also attempts to seek fulfilment through drinking, socialising and sex.

With consequences ranging from mundane to horrifying, it becomes clear that this way of living, or dying, is not for Maud. It is only when self-flagellating, or otherwise communicating with God that Maud experiences pleasure. When asked by Amanda if she gets a response when she prays, Maud replies ‘It’s like he’s physically in me. It’s how he guides me’. The physicality of these moments is evident when we see Maud feeling the exalted, bodily pleasure felt during God’s guidance. She writhes on floors, her eyes roll back, she gasps.

Besides these moments of almost orgasmic communication, we are privy as viewers to one instance where God addresses Maud directly. In a scene that feels reminiscent of the exchange between Thomasin and Black Philip in Robert Eggers’s The VVitch (also distributed by A24), Maud asks God for his guidance after she has been dismissed from Amanda’s home. Rather than asking if she would like to live deliciously, God answers, in Welsh, by telling her that she has always known what to do.

With its hallmarks of projectile vomiting and spontaneous levitation, Saint Maud shares the same trappings as the subgenre of demonic possession films. In such narratives, possessed young women to contort their bodies violently, swearing, hurling fluids and abuse. Not only do such films refract larger cultural anxieties about young femininity and the body, but they also (usually) require a man to save the day. Possessed women become flat stereotypes, needing to be exorcised, saved, avenged. Crucially, though, Maud is not possessed by a demonic force. She is not an unwilling vessel. She is possessed by God and her desire for purpose. And, when he answers her request for guidance, he does so in the language of her mother tongue. She drives the plot forwards by looking inwards. As much as this introspection takes place, Maud is also characterised by a certain watchfulness. Often seen looking at others – from a doorway, the outside of a party, or onto a conversation – Maud’s liminality throughout the film links to her position as an outsider and her wait for the arrival of meaning, but also the ambivalence which shrouds the narrative’s conclusion. Debates about what really happened to Maud aside, Glass’ debut feels fresh and distinctive. Abrupt and unnerving, it will leave you wanting more.

Saint Maud is streaming now.

Rosie Couch is an associate editor at Wales Arts Review.

Morfydd clark Morfydd clark Morfydd clark Morfydd clark Morfydd clark Morfydd clark Morfydd clark

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.