Rosie Couch reviews Beacons, a selection of short films created by Wales-based filmmakers which explores themes of bereavement, familial tension and love.

The Beacons short film fund, a collaboration between Ffilm Cymru, BFI NETWORK Wales, and BBC Wales supports filmmakers who are Welsh born, or based in Wales. The six shorts funded through Beacons have been airing incrementally on BBC Two since September 3rd, providing selected filmmakers with a valuable platform upon which to showcase their creative talents.

With short film, the space in which the narrative unfolds is necessarily smaller than that of longform cinema, entailing that filmmakers have to be all the more selective when thinking about the content that they would like to include. The result of such a process is less about limitation, and more about a selectivity that allows powerful, thoughtful, and diverse narratives to emerge. Whether they look at the humour and familial tensions underlying bereavement like Hannah Daniel and Georgia Lee’s Burial, or the stormy seas of a new relationship as with Efa Blosse-Mason’s beautifully animated Cwch Deilen (Leaf Boat), shorts construct punchy glimpses of the every day, snapshots of the subtleties and tensions that play out within our interactions with the world around us, and fantastical environments that imagine alternative ways of living.

In this sense, productive analogies can be made between short film as a form, and literary criticism regarding the short story, specifically with reference to Welsh filmmakers. In her introduction to the 1989 edited collection Re-reading the Short Story, Clare Hanson identifies how the short story operates as a ‘vehicle for different kinds of knowledge’ from that of more longform novels, instead conveying ‘knowledge which may be in some way at odds with the ‘story’ of dominant culture’. The short story mode, Hanson continues, lends itself to those who are ex-centric: ‘writers who for one reason or another have not been part of the ruling ‘narrative’ or epistemological/experiential framework of their society’. If you google ‘short films UK’, the majority of the top results feature filmmakers who are English, or based in London. Obviously, this focus on London and Englishness as the cultural centre of the UK algorithmically marginalises filmmakers who do not, and do not wish to, fit into either one of these categories, but it also overlooks a huge pool of talent within Welsh filmmaking especially. When the internet is such a prominent source of knowledge, this digital exclusion from short film listing extends to and upholds the ostracisation of Welsh film from broader film culture. It is arguably due to this ex-centric status – perhaps a double marginalisation, given that short film is already an ex-centric form – that the work coming from Wales is so strong in its construction of the style, themes, and stories that make short film itself so compelling.

The Beacons fund shines a light on Welsh short filmmaking, signalling and celebrating projects with ‘dynamic and distinctive voices, original storytelling, and visual flair’. And, this year’s offerings from filmmakers Hannah Daniel and Georgia Lee, Sion Thomas, Tina Pasotra, Joseph Ollman, Clare Sturges, and Efa Blosse-Mason certainly fit the bill.

Featuring across the selected shorts are themes of love, loss, and the instability of home and family. Though their tone is strikingly different, both Daniel and Lee’s Burial and Sturges’ The Arborist focus on the loss of a loved one. Burial tells the story of identical triplets, all portrayed by co-director and writer Daniel, as they attempt to make their way through their father’s funeral. Jumping between the previous stilted atmosphere of the civilised wake, and the present where the sisters are being interviewed by the police, the narrative slowly unveils underlying familial disputes and their associated tensions. Though these themes might sound particularly heavy, it is in fact a dark comedy, opening the opportunity for hilarious but also deeply meaningful assertions, such as Ani’s stand-out line at the wake: ‘He was more than this. He was more than… fucking quiche’.

On the other hand, The Arborist has very little dialogue, instead conveying the thematics and experience of loss through colour, light, and environment. The Arborist, a semi-autobiographical film drawing on Sturges’ experience of losing a twin, follows tree surgeon Laura (Catrin Stewart) as she returns to her childhood home following news that her twin’s memorial oak is dying. While the concept of a memorial tree feels like such a tangible, solid, and substantial way of remembering a loved one, it proves to be just as fallible and fragile as any other object, living being, or memory. Despite their contrasts, both The Arborist and Burial end on a fairly similar note: there is love, missing, but also the acceptance of a life that will be filled with that love and missing, and continue nonetheless.

Thematic strands regarding the unpredictability of environment and the transient nature of family and home also run through Thomas’ Dirt Ash Meat and Ollman’s Bitter Sky. Inspired by Owen Sheers’ novel White Ravens, Dirt Ash Meat follows Rhian (Catrin Stewart) and her brother Dewi (Rhys Rusbatch) as they attempt to keep their family farm operating within the context of the 2001 foot-and-mouth outbreak. Despite said context, as the characters witness the disease moving ever closer; Thomas’ short constructs uncanny parallels with the experience of living amongst the threat of COVID-19, as well as the impact of the pandemic on livelihood and family.

It would, however, be reductive to only discuss Dirt Ash Meat with reference to this comparison. In contrast to the matter-of-fact sparsity of Dirt Ash Meat’s title, the familial tensions and implications underlying Rhian and Dewi’s situation during the outbreak are much more complex. Like Burial and The Arborist, themes of loss are also present within Thomas’ short. As the future of the farm is endangered, questions of how Rhian and Dewi’s late father would have managed the situation are brought to the fore, bringing up questions of lineage and identity. If conceptions of home and family are pulled together by the raising of livestock, what happens to home and family when industry is taken away?

Like Dirt Ash Meat, Ollman’s Bitter Sky subverts the positioning of rural space as a site of serenity. Bitter Sky focuses on Nia (Darci Shaw), a 15-year-old girl from Liverpool, living with her adopted father Roy (Rowan Jones). Due to unknown circumstances, Nia has been separated from her mother who, as we find out from a short, interrupted phone call, is back residing in Liverpool. To escape from her temperamental, emotionally abusive adopted father and reunite with her mother, Nia has been fixing a broken-down car that she found within the woods. Beautifully illuminated by shots of the mid-Wales landscape, Nia’s feelings of isolation and alienation from ideas of home and family are palpable. Present within Bitter Sky and Dirt Ash Meat, however, are illustrations of feminine resilience, resulting in sudden and somewhat gratifying acts of violence which signify a seizing back of the control that has been taken from both Nia and Rhian throughout each narrative.

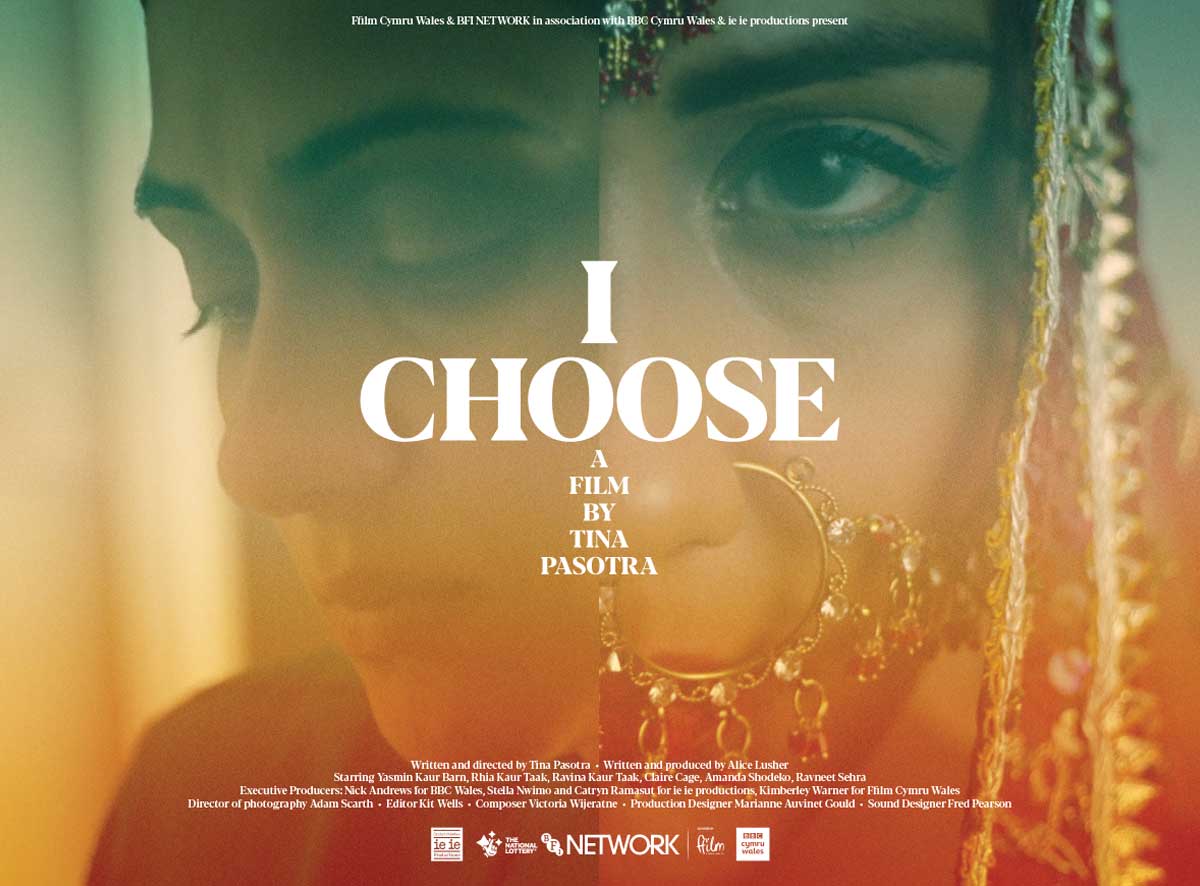

Strength, femininity, and agency are also key to Tina Pasotra’s I Choose and Efa Blosse-Mason’s Cwch Deilen. Central to Pasotra’s I Choose is the tenacity of protagonist Rupi (Yasmin Kaur Barn) in seeking a new life for herself and her two daughters in Wales. Like The Arborist and Bitter Sky, I Choose conveys both mood and emotion through visual elements rather than verbal elucidation. As Rupi cooks on her bare gas stove, vibrant shots of a woman in India also preparing chapattis enters the mise-en-scène, juxtaposing the blank, white walls of Rupi’s Welsh home. A similar contrast can be read between interposing images of Indian countryside and Rupi’s navigation around the beige walls of her surroundings, the smudged skies above her. This tonal vocabulary is less of a comment on Wales, and more about how the backdrop of Rupi’s environment reflects the despondence and constriction of her new life.

However, the instability of Rupi and her daughter’s existence in Wales stems from more than the return of past memories. As an unseen figure returns to their home one evening, Rupi visibly panics, tightening her pyjama bottoms and pulling her duvet close, suggesting that her feelings of nostalgia and isolation are also accompanied by an acute sense of danger. Rupi’s decision to leave this new home, persistent in her pursuit of a better life, positions Pasotra’s short as a striking and evocative account of resilience, strength, and love.

Love is also a driving force in Blosse-Mason’s Cwch Deilen, a Welsh-language animated short tracing the excitement, emotional obstacles, and anxieties of a new relationship. Cwch Deilen opens with Heledd and Celyn, watching the day pass by in a seaside town. The town, they decide, would be too small for them to live in. That, or their wings are too big – an observation that could serve as a salient commentary on how same-sex desire necessarily breaches the moorings of heteronormative culture. Like Rupi in Pasotra’s I Choose, Heledd and Celyn refuse to accept their environment as it and, instead, carve their own space in the world. Selecting elements within their reach – a leaf for a boat, a lamppost for a mast, and a blanket for a sail – Heledd and Celyn build their aquatic vessel and take to the seas.

Their journey is not always smooth sailing, with the escalating waves reflecting the delight and tumult of getting to know another person, a process which leads to the revelation of insecurities which threaten to capsize the relationship. Monsters rise from the watery depths, but, luckily, they’re easily placated with a cuppa. Discovered in the teapot some time later, the monster is small and timid, signifying how early disputes become endearing, cute even, despite how monumental they might have seemed in the greener years of a long-term relationship. Life might be wobbly and uncertain at times, but Heledd and Celyn are together and, like Rupi and her daughters, their love equips them with all of the strength and resilience that they could need.

All six Beacons films are available now to watch on BBC iPlayer

Rosie Couch is a contributing editor to Wales Arts Review and co-presents the Wales Arts Review Podcast.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.