Fedor Tot casts his eye over Frantz, the latest offering from François Ozon, reviewing his ability to offer a barrier against fear and hate.

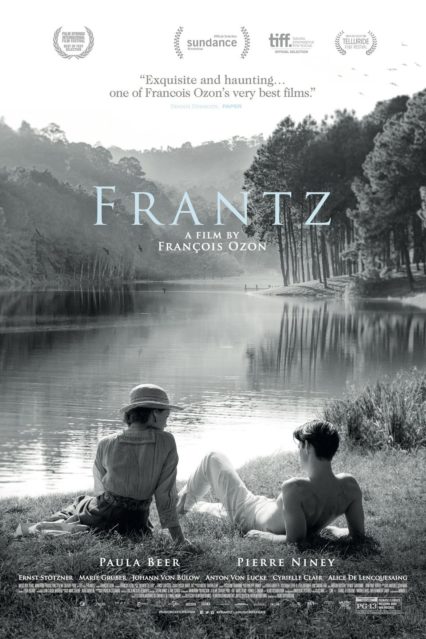

François Ozon has never been a director to pigeonhole easily, having prolifically worked in all manner of genre and style since his 1998 feature debut Sitcom. But even then, Frantz comes somewhere out of left-field for the director, who at the very least tends to make energetic, excitable movies full of colour. Set in the immediate aftermath of World War I, this is a stately, slow-paced film, carefully composed and constructed, and shot mostly in black-and-white, which tells the story of Anna (Paula Beer), whose husband-to-be, the Frantz of the title, was killed during the war. Living with his parents in the small German town of Quedlinburg, their mourning is one day disturbed by the arrival of a mysterious Frenchman, Adrien (Pierre Niney), who claims to have been Frantz’s friend during his studies in Paris.

Other reviewers have mistakenly called Frantz a remake of the mostly forgotten Ernst Lubitsch film Broken Lullaby, when in reality the two simply share the same source material by French playwright Maurice Rostand, The Man I Killed (Ozon has claimed in interviews that he came across the text first, unaware it had already been translated to the screen by Lubitsch). That said, it’s easy to see what drew both directors to this material.

Other reviewers have mistakenly called Frantz a remake of the mostly forgotten Ernst Lubitsch film Broken Lullaby, when in reality the two simply share the same source material by French playwright Maurice Rostand, The Man I Killed (Ozon has claimed in interviews that he came across the text first, unaware it had already been translated to the screen by Lubitsch). That said, it’s easy to see what drew both directors to this material.

Released in 1932, Broken Lullaby was released at a time when Europe was still recovering from the tragedy and loss of the war, but also a time when many European nations were experiencing a surge in nationalistic right-wing politics amidst the poverty of the Great Depression. More than a few commentators have noted the similarities between the Europe of the 1930s and the Europe of today; whilst Lubitsch would have been unaware of what lay ahead for his native Germany, Ozon today has the gift of hindsight, allowing him to imbue the source material with a sense of fatalism that offsets its sentimental nature.

The primary point of departure that Ozon opts for compared to previous versions of this material is that it chooses to view events from Anna’s eyes, rather than that of the French soldier coming to Germany to repent for his sins. When it is revealed that Adrien is not a friend of Frantz but the man who killed him on the battlefield – the original’s climax – Ozon instead chooses to carry on, focusing on Anna’s journey to Paris to try and track down Adrien. It’s a strong choice, leading to a more sensitive and interior film, backed up by the subtlety and depth of the performances. Both Anna and Adrien are characters who have a lot of interiority and suppressed emotions, communicating in reserved, cautious language as if not to fly too close to the flames, and it’s to both Paula Beer and Pierre Niney’s credit that they comfortably rise to the challenge.

The black-and-white cinematography is also handsome and stately. Dashes of colour, usually in flashback sequences to pre-war Paris or Germany are effective, as flowery as nostalgia often is. There are a handful of moments where Ozon opts to shift from black-and-white to colour and back again within the same shot. This device, in a film as otherwise understated and subtle as Frantz, is a thuddingly on-the-nose tactic and is the one aesthetic decision which feels not in service to the story, but more an element of directorial showboating. That said, its effect overall is minimally deployed.

Films that express a deeply humanist view of the world feel more prevalent today than, say, a decade or two ago, again as a result of the tumultuous change going on in the world today. Films like Frantz are an attempt to provide a bulwark against fear and hate, which is depicted here aplenty : Adrien can barely walk two steps in Germany without somebody giving him glares, and the pigsty patriotism of Anna’s admirer Kreutz (Johann von Bülow) threatens to destroy the tentative beginnings of a relationship between Adrien and Anna before it’s even begun.

One striking scene mirrors and subverts the famous ‘La Marseillaise’ moment in Casablanca. Where that scene functioned as a cathartically defiant moment in wartime USA on a production staffed mostly with European émigrés, here Ozon forces us to listen with Anna as she finds herself in a French café surrounded by patrons belting out the words, as if they are unaware of the sheer violence of the lyrics, already forgetting the lessons of the Great War: “Listen to the sound in the fields/the howling of these fearsome soldiers/they are coming into our midst/to cut the throats of your sons and consorts.” It’s by far the most electric moment in the film, which for all its qualities sometimes comes across as a bit too dry and polite, a meek reminder that nationalism and hatred are poisons rather than a full-throated roar against it.

Frantz is a fine work with a powerful message working beneath it, which Ozon doesn’t allow to become the central focus of the film. Instead our attentions are directed primarily to the relationship with Anna and Adrien, which is exquisitely crafted, told, and acted. There are a handful of aforementioned missteps, not least the reservedness of the film, but it certainly remains a solid film from one of the more unpredictable and interesting directors around today.

Fedor Tot is a Newport-based independent film critic and writer.