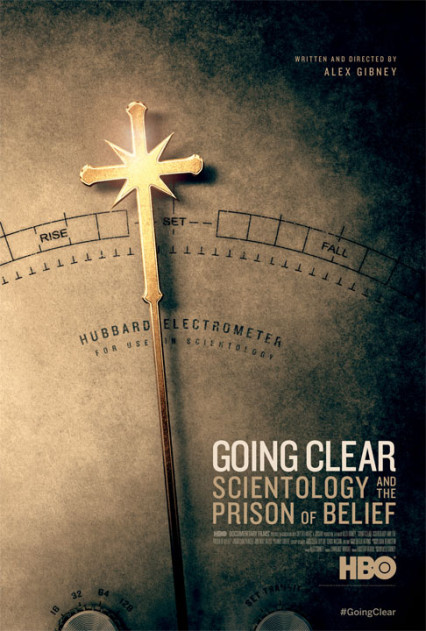

Gary Raymond finds a compassionate, horrifying, and familiar story in Alex Gibney’s HBO documentary on the Church of Scientology.

If there is any morbid interest in seeing two bullies fight it must only be in examining the different shades of cowardice of the combatants, and seeing who quivers and crumbles first. Such a curious spectacle is what is at the very centre of Alex Gibney’s controversial HBO film charting the 60 year phenomenon that is the Church of Scientology. In the early nineties, the US Internal Revenue Service finally brought to a head its decades-long investigation into the tax dealings of the organisation and slapped them with a bill of a billion dollars. At the time the ‘church’ was worth around $250m, and so, as is pointed out in the film, this was a matter of life and death.

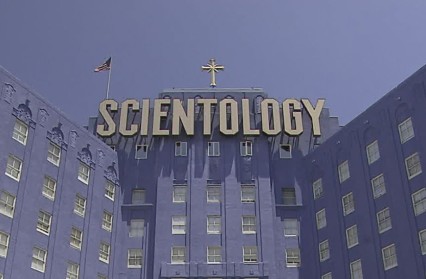

The response to this decision by the Church of Scientology was aggressive, bold, and amounted to a formidable campaign of torment and smears against the most feared of all government departments. The church members filed thousands and thousands of individual law suits against IRS agents and ran a media campaign that brow beat the IRS into submission. The IRS, in an act of sublime cowardice of which no-one really thought them capable, not only waved the debt but granted Scientology the status of ‘a religion’, a status in the United States that carries with it utter tax exemption. Today the Church of Scientology, with a membership that has dipped below 50,000, is now worth a little under $4 billion.

The response to this decision by the Church of Scientology was aggressive, bold, and amounted to a formidable campaign of torment and smears against the most feared of all government departments. The church members filed thousands and thousands of individual law suits against IRS agents and ran a media campaign that brow beat the IRS into submission. The IRS, in an act of sublime cowardice of which no-one really thought them capable, not only waved the debt but granted Scientology the status of ‘a religion’, a status in the United States that carries with it utter tax exemption. Today the Church of Scientology, with a membership that has dipped below 50,000, is now worth a little under $4 billion.

The story of the Church is a fascinating one – sometimes unbelievable – but this decision in 1993 is the defining moment. The Chairman of the Board, David Miscavige, the supreme church leader and successor to founder L. Ron Hubbard, is seen in Gibney’s movie delivering the news of their victory over the IRS to a massive congregation of scientologists at what can only be described as a rally. The backdrop to Miscavige’s speech is epic, garish. It is somewhere between a Cecil B De Mille stage and Stanley Tucci’s TV show in The Hunger Games. As former church head guy, Mark Rathbun says, ‘This wasn’t a victory speech, it was a coup.’ Much of the nature of Scientology, it becomes clear, is militaristic, and the church seems to lean toward the fetishist tendencies of fascistic symbolism often.

Gibney’s film, based on the book of the same name by Pulitzer-winning journalist Lawrence Wright, is peopled with former scientologists shamefacedly whistle-blowing what they saw during their blindness. Nobody has left the church unscathed, and those in this film – although scientologists of rank most of them – are but a few compared to the very many who are too scared to come forward. The Church has one policy toward those it perceives as an enemy, and that is aggressive and harassing. When Rathbun left his position as Inspector General of the Church in 2004, he was subjected to five years of harassment and intimidation by the church, to the point where they bought the house opposite his and filmed him and his family 24 hours a day.

It is clear that you cross the Church of Scientology at your own risk – if they beat up on the IRS who can’t they beat up on? But Gibney’s film is not one to linger on salaciousness. This aspect is not the bread and butter of the movie. Rather this is a very serious insight into the most successful cult America, land of cults, has ever produced. The questions Gibney is trying to answer are very simple – how and why has Scientology been so successful? And he goes some way to answering them.

Journalist and Scientology expert Tony Ortega says in the movie that the cult is in fact ‘a journey into the mind of L. Ron Hubbard, and the further you become immersed in Scientology, the more like Hubbard you become.’ That seems to be the tag line, and it is startlingly revealing. Scientology was founded by a figure who many found charismatic (it’s not easy to see why in these clips of him – he is at best creepy, the kind of guy you’d shuffle a few steps away from if you found yourself waiting at a bus stop with him), but a man who also despised psychoanalysis whilst purloining many of its techniques and more than once trying to commit himself into care in fear of his own sanity. Eventually those who succumbed to his ‘charisma’ came to worship him – there are several clips of congregations saluting murals that bear an image of LRH (as he’s known affectionately) long after his death in 1986.

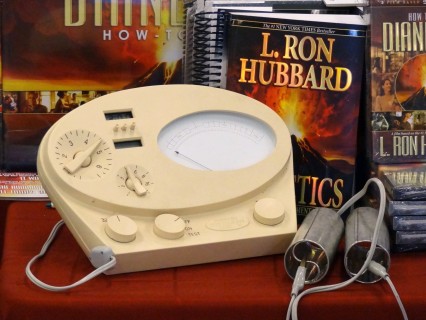

Hubbard was a Sci-Fi writer for pulp fiction magazines who still holds the Guinness world record for the number of books published (over a thousand). Much of his teachings which form the basis for Scientology can be found in those early Sci-Fi books of the thirties and forties. By the late-forties Hubbard is quoted as saying to his wife (who relays this in an FBI deposition) that the only way to make real money in the U.S. was to form your own religion. And from the publication of Dianetics (1950), the best-seller that is the bedrock of the Scientology faith, the whole thing has smacked of the money-making scam. Gibney, rightly, puts this up front, and it never fades from your eye-line.

It is important that Gibney strikes a very mature note in Going Clear when discussing the topic of individuals involved in Scientology. They may be brainwashed, but they are not victims; they may be gullible, but they are not idiots. These are life choices that are incomprehensible to outsiders, even more incomprehensible when Gibney presents a suffocating litany of evidence of the abuse, exploitation and degradation visited upon members of the Church. The stories of child slave labour, of violence, torture, and imprisonment, are not only presented with sensitivity and balance, but they are corroborated deep and wide, by both testimony and document. Miscavige himself comes across as a violent and delusional paranoiac. But, really, where does the blame lie? He was recruited to the Church at age 12 when his parents joined, and soon became LRH’s right hand man. The advanced teachings of Scientology’s Sci-Fi claptrap could not a healthy mind make.

And when the details of this advanced ‘theology’ is unveiled, then Going Clear reaches a level of supreme weirdness. To quote former Scientologist and Oscar-winning movie director, Paul Haggis, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?!?’ Again, this is an important value of Gibney’s film.

Haggis was the first big name to ‘come out’, as it were. When he blogged about his experiences of thirty years in the Church, it was picked up by major news networks in over sixty countries around the world. The Church has never really been able to recover ground from that moment, and Wright’s book, and Gibney’s film, are a result of Haggis’ blog, too.

Haggis explains that at first the Church of Scientology sells itself as an intense self-help organisation. (And it works: the Church teaches whatever goes right in your life is because of Scientology, and whatever goes wrong is the fault of you. Fail safe.) It also does bring with it a sense of community. There are stages of advancement through the Church, where a practitioner will attain new levels of ‘enlightenment’. Then on one of the highest stages, known as OT3, the practitioner is sat down and presented with a handwritten manuscript in which LRH reveals Scientology’s creation myth. This involves a 75 million year old Earth, (which is a space prison for a Galactic overlord named Xanu, by the way), and the explanation that humans are vessels for spiritual creatures known as Thetans, who were implanted by space ships into the bellies of volcanoes aeons ago. When a baby is born, the body is possessed by a Thetan (kind of like a soul), but it will also be possessed by many other spiritual creatures all vying for control of the body vessel. These are negative and corrupting invisible alien spirits. What Scientology does is help you discard these attached invisible bad alien spirits and become a ‘pure Thetan’. This is when the subject ‘goes clear’.

So yes; as Haggis said: ‘What the fuck are you talking about?’

Here there are two wider questions, of course; both of which are thrown up in Gibney’s film. What precisely makes this bullshit any different to the creation myths of any of the other organised religions operating in the U.S. (and around the world) right now? All of them have tax breaks, too. The idea of the Thetan is remarkably similar to that of Christian gnostic arguments, and there are flashes of now old-fashioned ideas of the Holy Trinity in the Catholic Church. Casting out demons and invisible visitors is not the preserve of one deranged Sci-Fi writer. And time and time again notions are thrown up in Gibney’s documentary that are not so unfamiliar when you strip them down from their jargon and quasi-philosophical garb. The Church is obsessed with control – they designate ‘Suppressive Persons’, those who are critics of the Church, and they ‘Disengage’ people from the Church who turn critical, and they ‘Disconnect’ that person from their friends and family. A Suppressive Person, or SP, is completely cut off and damned. Which sounds an awful lot like the threat of excommunication to me.

If you want further allusions: the church is obscenely wealthy for its size – it drains its congregation financially; and Miscavige is often referred to as ‘the Pope’. However, unlike in, say, Mormonism, Scientology seems to have no corrosive obsession with Eschatology, and Mitt Romney almost became President.

So, Scientology sounds like a religion as far as my understanding goes, and not even the most deranged; so leave them to it, to each his own, and Gibney does not leave out the statements of sincerity that the church has done much good for individuals in their lives – particularly in the early days before Miscavige took over. So why do people leave? The same reason why this film, and its subject, remains so intriguing: the evil within – the corruption and abuse and darkness that is not just put up with by the Church members, but is part of their life blood.

There are many examples of many Church members undergoing oppression and humiliation and exploitation that you might expect to see in a Gulag (I am not exaggerating for effect), and not only do thousands of them stay, ‘Disconnecting’ from family to do so, but they stay with aggressive passion for their faith.

So what next for the Church of Scientology? Going Clear is ultimately a damning portrait of an organised religion founded a few thousand year too late to dine on the top table. (Who knows, had LRH been born in Roman Galilee we may all have been battling our invasive Thetan spirits every Sunday morning). But its congregation is dwindling, and at its helm is a paranoid despot who regularly ‘clears out’ his offices of high-ranking subordinates in fear of an organised rebellion. It is a laughing stock globally. But its wealth brings it influence and power (due to libel laws, the Church has stopped Going Clear from being screened in the UK indefinitely – luckily I had it beamed directly into my brain from an Argoth Transmitter from the Seventh Dimension of Yanuth, which circumnavigates such Earthly laws).

But it does feel like the end is nigh. Tom Cruise, its golden boy, may bring in box office on the back of that cheeky smile, but he has never recovered from dancing on Oprah’s sofa, and Going Clear presents him as mean-spirited adolescent utterly under the control of Miscavige. (This control seems to be based mainly on a regime that Miscavige ensures the Church makes every day Cruise’s 8th birthday party). People like John Travolta, the Church’s first golden boy, are likewise not taken very seriously any more. In this film Travolta comes across as a coward of the worst kind, ignoring the very real abuse and torment to one of his closest and most loyal friends and her infant child in favour of sticking with his church ‘of joy’. For all of the nuances and human complexities (and many sympathies) of this film, it is the high-end celebrities of Cruise and Travolta who come out with no redemption, as people fully aware of the slave labour and child-exploitation that builds their luxury complexes and the abusive prison camps that ‘correct’ Church members who transgress. They really will turn your stomach.

But all in all Going Clear is not the hatchet job many might hope for. It is a thoughtful movie concerned with the complexities of anthropology and psychology. Scientology can be ridiculed quite rightly for many reasons, and reviled for many more, but when that is all done there are some wider questions left standing about what society without a central faith system might look like, and why it seems so difficult to be without such a society.

(Photo images under general license)

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.