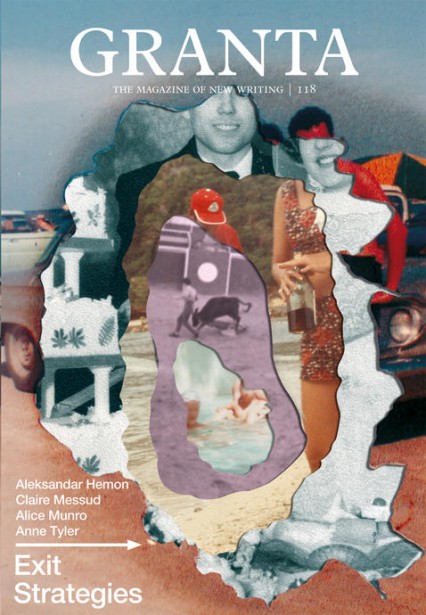

John Lavin examines the latest edition of the Granta magazine; Granta 118: Exit Strategies Edited by John Freeman.

Granta 118: Exit Strategies begins and ends with two memoirs. Claire Messud’s chronicle of her father’s death, ‘The Road to Damascus’, and Alexsandar Hemon’s account of the Bosnian War via the medium of his families’ beloved red setter (the ironically titled ‘War Dogs.’) In between we are treated to a series of significant departures, the majority of which highlight human helplessness. Helplessness in the face of death, Alzheimer’s or simply the ability to have a positive impact on another individual’s life.

The collection boasts new pieces from two of the world’s most celebrated writers: Alice Munro and Anne Tyler. Munro, in particular, appears to be incapable of writing anything other than masterpieces these days and ‘In Sight of the Lake’ represents yet another perfectly judged insight into the human condition. Returning to Alzheimer’s –

Edited by John Freeman

256 pp, £12.99

The extract from Anne Tyler’s new novel, The Beginner’s Goodbye, is an account of a husband’s coping mechanisms in the first days and weeks after his wife has been killed by a tree falling onto their house. Even though the house is mostly unusable he insists on living there until it becomes impossible to do so. As ever Tyler has an impressive grasp of male psychology and the piece is a typically understated triumph.

There are also two pieces from two of our great literary elder-

Rich’s poignant ‘Endpapers’ finds the poet looking back at her life and work and declaring that:

The signature to a life requires

… a sheet of paper held steady

after the end-

above a deciphering flame.

There is thought-

Here spills were expected. Because we were just Africans. What did Shell care?

In Newberry’s ‘Summer’ a group of four gay male friends meet up in Mississippi each year to try and recapture the sense of freedom and abandon that they had experienced the first summer they had spent together, a period in which the story’s narrator had come out. He remembers how he once, in tears, told his friends:

I never thought I’d have the strength to live like this.

But the story’s defining moment comes when his friend Jay announces he is going to marry a woman he had dated before he came out himself. Although Jay is not physically attracted to the woman he considers it an exit strategy worth taking. An escape route out of a life of loneliness and parental condemnation.

It is also worth mentioning Stacy Kranitz’s eerily beautiful photos of the Isle de Jean Charles in the Gulf of Mexico. It is an island which ‘is now one third the size it was when Native Americans first settled there in 1876, fleeing south to avoid enslavement.’ An island which finds itself slowly disappearing into the water while the US government looks impassively on.

Indeed the only dud note in an otherwise brave and arresting collection is David Long’s inexplicably poor ‘Bonfire’; a story which is solely memorable for containing some of the worst writing on the subject of sex this side of Nuts magazine:

You know what? she said. You should take your pants off before they rip.

Well, it was true, he was scary hard.

A minute or two later, she was straddling him, rocking semi-

But this is a minor oversight in a collection with more than its fair share of riches. A collection that, in typical Granta tradition, somehow manages to transcend the sum of its parts. Leaving us with a sense, not only of human helplessness, but also of human kindness and wonder.