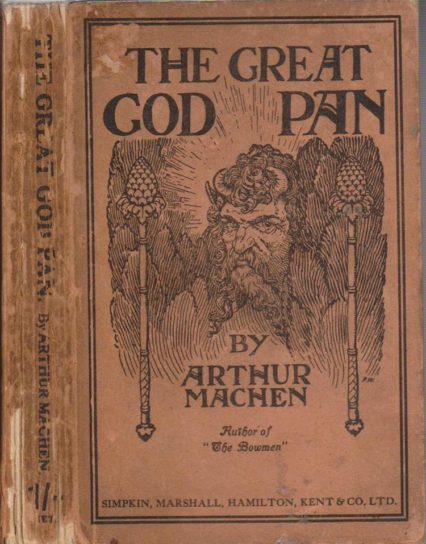

As we continue our search for the Greatest Welsh Novel, Phil Morris nominates the classic horror/fantasy novella The Great God Pan by Arthur Machen.

Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan opens with a mad scientist, Dr Raymond, performing a botched experiment in late-Victorian brain surgery on a young woman, Mary, who is rendered insane after being granted a momentary glimpse into the noumenal universe that exists beyond our own world of surface, though illusory, realities – and then it gets even stranger.

Like his fellow masters of the supernatural – Edgar Allan Poe and M.R. James – Machen does not shock his readers with gory descriptions of bloody violence, nor terrify with evocations of scary monsters red in tooth and claw; but rather he works his dark magic by affecting a creeping sense of dread, with what his admirer H.P. Lovecraft described as a ‘cumulative suspense… with which every paragraph abounds’.

At the heart of The Great God Pan is the mysterious figure of Helen Vaughan and the unholy fascination she exerts over the young, rich men of fin-de-siècle London. Like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Machen’s novella elides intense sexual allure with a secret undisclosed evil that lurks beneath the shimmering surface of physical beauty. Only, in Machen’s case, the book speaks to Victorian anxieties about the sexual agency of women rather than the decadence of aesthetes. The beauty of Helen Vaughan is not described in any detail, it is the effect of her beauty, its soul-corrupting voluptuousness, on others that is of interest to Machen.

At the heart of The Great God Pan is the mysterious figure of Helen Vaughan and the unholy fascination she exerts over the young, rich men of fin-de-siècle London. Like Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, Machen’s novella elides intense sexual allure with a secret undisclosed evil that lurks beneath the shimmering surface of physical beauty. Only, in Machen’s case, the book speaks to Victorian anxieties about the sexual agency of women rather than the decadence of aesthetes. The beauty of Helen Vaughan is not described in any detail, it is the effect of her beauty, its soul-corrupting voluptuousness, on others that is of interest to Machen.

Machen’s powerful capacity to disturb lies not in what is described and explained but what is indicated and unsaid. His plot bounds forward in big leaps in which the narration skips from the impressionable young Clarke to Vaughan’s nemesis Villers, the story unfolding in a series of gossipy accounts, journal entries and stories within stories. Jon Gower accurately described The Great God Pan as ‘a Matryoshka confection, a Russian doll full to the brim with seeping, foggy menace, inexplicable deaths and resurrections’. The reader is frequently knocked off balance by a sudden shift in time and place – speculation about Helen’s death is confounded by rumours of her sexual adventures in South America, years later another mysterious woman turns up in London with a host of young suicides trailing in her wake – could this lethal Mrs Beaumont be the same Helen Vaughan?

Underneath all these tantalising narrative mysteries there lies the deeper existential conundrum that Machen locates in the landscape of Gwent, where the novella begins. In his autobiography Far Off Things, Machen presents his birthplace of Caerleon, and its surrounding countryside, as some form of transcendental portal in which prevailing notions of time and space can be collapsed or exploded. For him, Gwent was not merely a place of boyhood dreaming, but also a means by which the universe beyond the obscuring veil of our perceived ‘real’ world could be perceived as it truly is. In the gripping opening chapter of The Great God Pan, the sinister Dr Raymond makes this challenge to his friend Clarke on the notion of perception and reality:

You see the mountain, and hill following after hill, as wave on wave, you see the woods and orchard, and the fields of ripe corn, and the meadows reaching to the reed-beds by the river… I say that all these are but dreams and shadows; the shadows that hide the real world from our eyes. There is a real world, but it is beyond this glamour and this vision, beyond these ‘chases in Arras, dreams in a career’, beyond them all as beyond a veil.

Machen’s aim in his fiction was always to ‘depict the eternal, inner realities – the things that really are of Plato – as opposed to the description of transitory external surfaces; the delusory masks and dominoes with which the human heart drapes and hides itself.’ Which is why, in spite of Machen’s sometimes overblown and often clunky prose, The Great God Pan still manages to get under the skin of its readers. Its unknowable anti-heroine, its dark implications, its structural lacunae, and its expressions of awe in the face of the ineffable mystery of our universe, directly addresses our concerns regarding the odd impulses that emanate occasionally from our Id, the highly subjective nature of perception, and the limitations of human knowledge. Much scarier than a mere monster is the idea that we don’t really know who we are, why we’re here and what is our purpose. The novella also touches on our contemporary fears regarding the medical modification of human subjects. Machen’s work lingers long in the mind after reading, not because it features the Gothic staples of wicked women, inherited satanic evil and damned souls, but because it reawakens our own suspicion that reality is something that we only ever dimly perceive and always fail to comprehend.

The influence of Machen can be found in the works of later writers, such as H.P. Lovecraft and Peter Straub, and the films of Guillermo Del Toro. Stephen King acknowledged that he was ‘strongly influenced’ by Machen’s The Great God Pan in the writing of his own novella N. King noted how Machen works his way ‘relentlessly into the reader’s terror-zone’.

In another interview King stated: ‘Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan…is one of the best horror stories ever written. Maybe the best in the English language. Mine isn’t anywhere near that good, but I loved the chance to put neurotic behaviour – obsessive/compulsive disorder – together with the idea of a monster-filled macroverse’. Such a tribute from a modern master of horror fiction should encourage many modern readers to appraise themselves of Machen’s work.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s ‘Greatest Welsh Novel’ series.

Phil Morris is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.